The tragic life of Michael Cimino: Hollywood’s most notorious failure

A new biography reveals that the director of ‘The Deer Hunter’ had a private life cloaked in mystery. After the epic flop of ‘Heaven’s Gate’ the filmmaker became a recluse, changed looks and presented as a woman in private

Hollywood by nature tells its stories in legendary terms, and the narration of the life and work of Michael Cimino (New York 1939 – Los Angeles, 2016) is no exception. This shocking biography pulls out all the stops. After winning two Oscars for The Deer Hunter Cimino was shunned from Hollywood for the historic failure Heaven’s Gate in 1981. It was this blow that compelled the director to shut himself up for the last 20 years of his life, feeding a story of speculation, mystery, and rumor. Another book now adds to this mystery, suggesting that the director spent the final stage of his life as a transgender person.

The director gave his own account of his childhood, which he described as “out of a play by (the depressing playwright) Eugene O’Neil”: he felt ignored in his family home on Long Island, spending afternoons in the basement with his tall, strong brothers who took after his father and made him feel small. This spurred him to take up wrestling in high school. “I don’t want to talk about my family, it’s too painful. Everything about it hurts.” He explained. He said that his mother never responded to his success. Upon finishing high school, he moved to Manhattan, changed the pronunciation of his surname, and cut all ties with childhood friends. The only thing that he took to his new life was a warning, appearing next to his picture in the school yearbook: “You better not fight this guy.”

“He invented himself: he was almost a fictional character” remarks Charles Elton in the recently published Cimino: The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate, and the Price of a Vision (Abrams Book). The future director would tell people that he had fought in Vietnam, but a New York Times correspondent published a story that stated Cimino enlisted in the Army three years before the first US troops arrived in Vietnam. It would seem he spent just five months in the military and never wore the green beret.

Another of his most emblematic lies was his age: he claimed he was born in 1952, when it was really in 1939. This made him seem like a child prodigy when, in 1978, he wrote, shot, and won two Oscars (film and director) for The Deer Hunter. He was supposedly just 26 years old, the same age as Orson Welles when he made Citizen Kane. The Deer Hunter, Cimino’s psychological drama about the Vietnam War starring Robert de Niro, Meryl Streep and Christopher Walken, exceeded its budget (from €6 million to €12 million) because of his obsessive attention to detail. When editing began, the director took 12 weeks just to see everything he’d shot. But then the praises started pouring in and moviegoers walked out of theaters hugging and crying. It grossed €50 million and so Hollywood forgave Michael Cimino for all his snobbery and objections. “Tell the studio what it wants to hear,” the director recommended, “and then do what you want.”

After winning the Oscar, Cimino began filming an epic drama about border conflicts in late 19th century America. A clause in his contract stipulated that the title of the movie would be Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, with his name in letters as large as the title on all billboards. Six days into the shoot, he was already five days behind schedule.

The director banned journalists and even United Artists executives from the set, a secrecy that only fueled the rumors. It was said that Cimino had ordered the destruction and rebuilding of an entire street set so that the shoulder lane would be four centimeters wider, that he had a €50,000 budget for cocaine, and that he had burned an entire set just to see what it looked like. The planned 69 days of filming became more than 200. When they finished, actor John Hurt bought a farm and named it The House of Overtime.

The then vice president of United Artists, Steven Bach, maintained that if Cimino came across as a ruthless man “it was more because of imprudence than conviction.” He was compelled to say this since the stories of egotistical cruelty associated with the filmmaker were starting to become overshadowed by a shoot full of mishaps. His assistant started dating one the crew: Cimino fired him immediately. He also fired his lawyer for being unreachable on a Sunday, and he eventually lost two of his best friends. “Don’t ever refuse to do what I order you to do again” he yelled at one of them. In his neurosis, he suspected they were studio spies.

Cimino installed bars on the window in the cutting room and changed the lock periodically. He boasted that had cut the movie and was also responsible for its soundtrack and photography; functions he claimed he had already performed in The Deer Hunter. As the premiere approached, he refused to cut a single minute of the 229. But the filmmaker kept his cool: “Everyone hates me until they start receiving Oscars” he used to say.

Heaven’s Gate is one of the most talked-about movies that few people have seen. In The New York Times, Vincent Canby defined it as “an unqualified disaster,” the critic Robert Ebert called it “the most scandalous cinematic waste I have ever seen,” and in the Beverly Hills polo club, a group of producers read the reviews aloud, applauding each insult. The box office generated just over $3 million, less than a tenth of what it had cost. It became a symbol of the arrogance and megalomania of the Hollywood authors of the 70s, as brilliant as they were volatile, and so counterproductive for the economy. “Heaven’s Gate undercut all of us” regretted Martin Scorsese “I knew at the time it was the end of something, that something had died.” In September of that same 1981, journalist Michael Dempsey, announced the beginning of “Hollywood post-Cimino” in American Film magazine.

During the 1980s, Michael Cimino represented the boogeyman for studios. Nobody wanted to bet on auteur cinema: the power returned to the producers. Two years later, United Artists, producers of huge hits such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo Nest (1975), Rocky (1976) or Last Tango in Paris (1972), declared bankruptcy. Cimino’s punishment had to be exemplary so that no presumptuous director would push around an executive ever again. It wasn’t enough to humiliate him. He had to been banned.

Cimino went on to shoot four more movies, but without the freedom he had enjoyed until then. “It was like hiring Picasso and tying his hands behind his back”, claimed his unconditional ally, the producer Joann Carelli. The doors to Michael Cimino’s home on Alto Cedro Drive, both a refuge and a prison, were barely opened again. His isolation took on a mystical dimension, like that of J.D. Salinger. He stopped answering the few calls he received and even fired his secretary when she got pregnant.

Cimino spent his days writing. He wrote film scripts, adapted them into novels and stacked them to make paper towers that ended up scattered all over the floor of his office following several earthquakes. He decided to lock up his office and never open it again. It’s believed that 50 manuscripts are still lying there. In 2004, Steven Bach, vice president of United Artists was asked if he held a grudge against Cimino, to which he responded: “It would be like wishing ill on a corpse.”

He wrote his memoirs. They started like this “I am a myth. I barely smile anymore. The pool is empty. It’s been like this for 15 years.” Cimino created an alter ego who spent his nights drinking, self-medicating, and “playing around with anorexia.” He went two days without eating, and according to his friend Cynthia Lee Duck, he only ate fruit, lettuce, and nuts. “I’ve hit rock bottom” lamented the protagonist of the memoirs. “I think I am dead, and somebody has taken my place. I don’t recognize this person.”

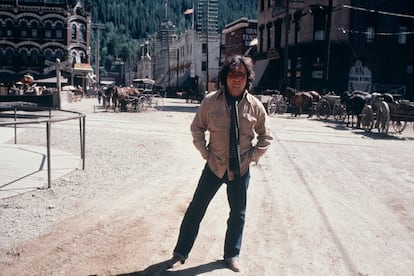

In Elton’s book, one of Cimino’s closest associates, Pablo Ferro, recalls hearing him repeat “I don’t want to be Michael Cimino anymore.” He achieved this with his physical appearance. That short, plump Italian American “with the look of a garage mechanic,” as he’d been described in the 70s, had been transformed through alleged cosmetic surgeries that he always denied, into something completely different. “He looks like Bette Davis at the end of her life,” wrote a journalist. “It’s a cross between a cowboy and your Aunt Bessie,” joked another.

It was said he had applied for a name change in the directors’ union, to “Michelle Cimino,” that he had been seen dressed as a woman in a London zoo, that during a flight he had entered the toilet in male attire and had come out wearing a dress, a wig, and lipstick. “She was a perfectionist” Feeney warms in Cimino. “She would only have done it if she could look like Catherine Deneuve.” Elton interviews one of the few friends Cimino kept during those last years of her seclusion. “When she came to see me, she introduced herself as Nikki,” recalls Valerie Driscoll.

Driscoll opened a business for men who want to dress as women. Having worked as a salesperson in a wig store, she realized her male clientele would be more comfortable going to a safe, discreet place. According to Driscoll, Nikki requested her help to be transformed “into a beautiful woman.”

Driscoll describes this person as “sweet, soft, and particularly naïve,” adjectives that coincide with his latest appearance at festivals, such as Cannes, or in film club retrospectives. “His behavior was just as altered as his physical appearance,” Elton observes. “Before, Cimino’s public persona was solemn and unforgiving, without a trace of humor. Now, in Europe, she showed great charm and even beguiling eccentricity.”

Contributing to this newfound joy was the restoration in 2012 of the nearly four-hour original film of Heaven’s Gate, presumed lost until a copy turned up in a London warehouse. Critics celebrated it as one of the great masterpieces of American cinema. A movie, that just as Bach had admired in 1980, managed to capture “the poetry of the USA.” In a symposium at the Locarno festival, Cimino went down to the stalls and walked among the public, giving out kisses, hugs, and good wishes, and even started singing Can’t Take My Eyes Off You, as De Niro had done in The Deer Hunter. This new persona had nothing to do with the fierce Cimino as the legend told. Cimino was as surprised as anybody else: “I googled myself once and I don’t know most of the people I’ve been.”

Valerie Driscoll recalls how Cimino suddenly stopped responding to phone calls. “As she got older, my wand didn’t work as well. Our last few sessions didn’t end with such exciting transformations as previous ones. We both realized that the days of glamor were over,” she laments. The director’s nephew, Christopher, recounts that during the last few years Cimino always wore sunglasses and was “the spitting image of his mother.”

Cimino passed away between June 28 and 30, 2016. The press reported that he had died peacefully surrounded by relatives, but that was the penultimate lie in the Cimino myth: the director died alone. And in Charles Elton’s book, several friends admit that they suspect suicide.

Elton managed to track down Peter Cimino, the director’s brother, who says he hadn’t heard a word from Michael since the mid-80s. He also made perfectly clear that his mother, far from being the woman unmoved by her son’s success that she had been described as, “spent those three decades collecting clippings and waiting for a surprise visit from Mike.” He describes a normal, uneventful childhood, at odds with the one his brother used to describe. “That childhood was too ordinary to make a good story,” notes Charles Elton. “And Michal Cimino, above all else, loved a good story.”

Translated by Xanthe Holloway

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.