In southern Spain, an iconic sculpture’s true colors shine through 2,400 years later

Photographic techniques were used on the Lady of Baza, a leading example of Iberian art, to uncover the pigments used by the original artist in the 4th century BC

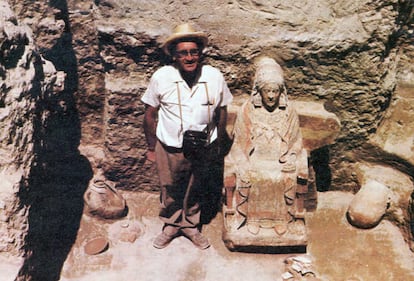

On July 20, 1971, an archeologist named Francisco Presedo made a discovery that brought him world fame. During digs at a necropolis on a hill named Cerro del Santuario, in the city of Baza in Spain’s southern Granada province, he opened up a cavity that was 2.60 meters wide and 1.80 meters deep. Inside, he found a painted sculpture of a seated woman together with a rich array of burial goods including weapons, all of which had lain there for around 2,400 years.

Presedo had just found what would become known as the Lady of Baza (la Dama de Baza), a spectacular sculpture made by an artist belonging to the Bastetani, a pre-Roman people who lived in the Iberian peninsula’s southeastern region between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC. Its name is reminiscent of another, more famous sculpture made during the same period, the Lady of Elche.

But it was not all good news that day. To his horror, the archeologist quickly discovered that the sculpture’s original colors were fading away by the hour. He also found a brownish stain caused by water leaks. In a desperate attempt to stop the decaying process, Presedo grabbed a can of hairspray and covered the Lady of Baza with it.

But now, scholars are using 21st-century technology to restore the palette of colors – ranging from blue to silver – that were used by the original artist. The findings are explained in a study called La Dama de Baza. Nuevas aportaciones a su estudio iconográfico a través del color y la fotografía (or, The Lady of Baza. New contributions to its iconographic study through color and photography), by Teresa Chapa Brunet, María Belén Deamos, Alicia Rodero, Pedro Saura and Raquel Asiaín.

Chapa Brunet, a professor of prehistory at Madrid’s Complutense University, underscores “the dearth of photographic evidence about the moment of discovery of the Dama de Baza, since all we have is what Presedo published in his studies, as well as a few images from his estate. And there are some pictures by other people who showed up at the dig after hearing about the Dama, and which were later printed in newspapers.”

In order to restore the lost color and details, experts relied “on digital photographs that allow for a detailed observation of the image and let you highlight specific aspects.” Pedro Saura, a professor of photography at Complutense University, notes that “the vast majority of elements or subjects receiving light will reflect it in a diffuse, specular way in varying proportions. Reflected specular light is what we think of as ‘shiny.’ Depending on the surface of the elements, the proportion of light that is reflected back can be higher or lower. Culturally, and because we use our own vision as a reference, we are used to accepting these spots of brightness without being completely aware of them.” In other words, our brain accepts the colors it receives, even though they include reflected light that can be avoided with photographic filters.

And so Chapa Brunet’s team eliminated nearly 100% of this reflected light. The first result was that the sculpture’s colors came across with greater intensity. And “several motifs that were hardly noticeable before” became visible. This made it possible to see the Lady of Baza “as the image of a real Iberian woman, distinguished, representing the upper and wealthier classes of society, but also someone who sought personal protection with small, well-concealed elements of her clothing.”

The report notes that “the workshop where she was created and painted wanted to faithfully reproduce the [real woman’s] physical looks and dress by coloring the face and hands in nuanced skin tones and painting the cloak and tunic in the colors that were really worn.”

The original artist also devoted plenty of time to the chair or throne that the figure sits in, “where there is a play of light and dark colors presumably matching the way that the piece of furniture was painted or the slats of wood combined.”

In 1990 and again in 2006, the University of Valencia and Spain’s Institute for Cultural Heritage applied the most advanced analytical techniques available to identify the pigments that were used on the sculpture: calcium copper silicate for Egyptian blue, cinnabar for vermilion, earth for ochre, plaster for white and coal for black. They also detected the presence of very fine copper leaf sheets covering the jewels to make them look silvery.

The new study also underscores that “the color on her cheeks is brighter, and becomes more intense on the lips, also painted with cinnabar. On the face, black was used for the eyebrows, eyelid margins and eyelashes, the latter being painted over fine indentations to highlight small eyes that would have been expressive through painted irises and pupils, although this has been lost, leading to her current absent look, as though gazing out without seeing anything.”

Computer treatment of digital images also allowed researchers to “bring into greater focus a motif that nobody was able to identify back in the day and which nobody had noticed: a long string of beads hanging from the back of the pendants, snaking up and down.” This element was painted vermilion, same as the edging of the cloak and the tunic, leading scholars to believe that it was “a string with knots” with more of a symbolic than a material value. “We wonder if it might be a traditional formula for personal protection, reinforcing the talismanic action of the Lady’s necklaces,” says Chapa Brunet.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.