When your district goes trendy: neighborhood resistance in Barcelona

Gentifrication is pushing residents out of the central Sant Antoni area as rent prices soar and hip retailers take over

“Leaving Sant Antoni would be too much of a blow for me and my family,” says Ferran Brunet, who was born and bred in this downtown neighborhood of Barcelona.

Brunet still lives there, but he fears that the long-term relationship might be coming to an end. His apartment is scarcely a 10-minute walk away from La Rambla, and 15 minutes from Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia basilica. Tourists and newcomers are drawn to Sant Antoni like bees to honey, according to the locals. “And it used to be ours,” Brunet says.

Skyrocketing rents, along with commercial metamorphosis, are making it difficult for tenants such as Brunet to remain in their lifelong neighborhood.

Brunet is an engineer and a father of two. His wife is unemployed. Last November, the landlord informed them that the rent would go up from €700 to €1,100 within a month, as their old lease was expiring. They could scarcely afford it.

The average rent in the Catalan capital was €681 in 2013. In 2018, it had increased to a record figure of €929

“We fought back and, at least we got a one-year extension on our old contract,” he says. But he doesn’t know what will happen 12 months from now. He is afraid the rent may force the family to move to a cheaper district in Barcelona. They would not be the first, nor the last.

Within the next three years, as many as 3,500 families in Sant Antoni will have to renew their rental contracts, according to Fem Sant Antoni (FSA), an association created in 2017 to defend vulnerable residents. Together, they aim to fight growing problems such as evictions and speculation in the housing market.

Up-to-date statistics show a clear upward trend in prices. According to a report from Barcelona City Council dated June 2018, the value of a square meter in Sant Antoni has gone up from €10 to €13 in the last four years, representing a 30% increase.

This price inflation is affecting the whole of Barcelona. The average rent in the Catalan capital was €681 in 2013. In 2018, it had increased to a record figure of €929, according to the Chamber of Private Property of Barcelona.

But the price hikes in Sant Antoni are also a reflection of the district’s human and urban landscape transformation. Its streets are going trendy and modern new shops are opening up. “Fancy bistros, hipster cafes, expensive boutiques, even dog-clothing stores. Those are of no use to the average Sant Antoni neighbor,” says local resident Araceli Casado.

Casado recalls Bar Calders, located on Parlament street, as the first “cool” bar around, back in 2011. Now, even the Michelin-starred chefs Ferran and Albert Adrià have five restaurants in Sant Antoni. “It’s hard to find a cheap spot to have a beer,” notes Casado.

Sant Antoni, home to 38,000 residents, didn’t use to appear in tourist guides. Following Barcelona’s Eixample – the great district built as Barcelona expanded in the late 19th and early 20th century – Sant Antoni has always been a plain residential area.

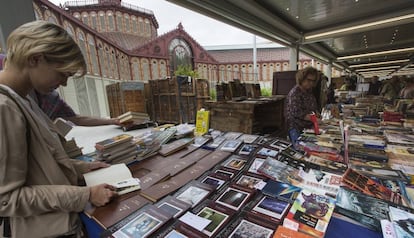

“In Sant Antoni there is no Sagrada Família, no Casa Batlló... but now we have the market,” says Jesus Fabà, a member of FSA. This Art Noveau building in the heart of Sant Antoni has been at the epicenter of neighborhood activity since its creation in 1882.

In May 2018, after a nine-year-long refurbishment, the market reopened as a brand new landmark for the district that stirs both pride and concern among the neighbors, as some fear that prices will go higher up still.

New players

There is a word for what’s happening in Sant Antoni: gentrification. As defined by the Oxford Dictionary, it is “the process of renovating and improving a district so that it conforms to middle-class taste.” “It is accompanied by an influx of affluent people and often results in the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents,” says the Merriam-Webster dictionary.

Many people have been forced to leave flee Sant Antoni, and new residents are taking over. “There are many European professionals who come here to work, with wages that allow them to pay high rents,” says Araceli Casado. “These are the ones who go to Bar Calders,” adds FSA spokesman Vladimir Olivella.

Such a place is perfect terrain for real estate agencies. More than 25 are working in the district already, according to FSA. Their strategy: getting hold of as many apartments as possible so they can be rented or sold at higher prices.

“An old lady died some months ago, and at her burial there were already estate agents calling to buy her apartment,” says Casado. She has had many of them knocking on her own door. “They always offer me a valuation for my apartment.”

So-called vulture funds are also nesting in the district, Casado says. “They buy entire buildings, often with tenants inside.”

In early March, Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau announced a €2.8-million fine for two of these investment funds that had kept two residential buildings empty for years, representing 24 homes.

Many of these uninhabited properties may end up, after some refurbishment, on platforms such as Airbnb. There are up to 1,300 tourist apartments in Sant Antoni, according to FSA. Despite half of them having no legal license, international visitors are still flooding in. “You see people strolling with suitcases everywhere,” says Ferran Brunet.

Neighbors, united

According to the last local survey, affordable housing is the main political problem for citizens in Barcelona. As such, many neighborhood associations such as FSA have emerged throughout the city. Their manifestos call for housing to be considered a “social right, not a commercial stock.”

Two Wednesdays a month, Araceli, Vladimir, Jesús and other residents in Sant Antoni gather to plan their actions and to seek counsel. Their fight is mainly on the legal side – there’s always a lot of fine print to be read – but they often have to go out on the streets as well. Many neighbors are being kicked out by rising rents without fighting back.

“We have stopped more than 10 evictions,” says Araceli Casado. “But there are still too many silent ones that we don’t know about.”

An Elpais.cat project

Since November 2016, the Catalan edition of EL PAÍS, Elpais.cat, has been publishing a selection of news stories in English.

The texts are prepared by journalism students at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), who adapt content from EL PAÍS, adding extra information and background to these stories so that they can be understood in a global context.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.