Donald Trump’s lies about Haitians raise racial tensions in Springfield

Migrants from the Caribbean country living in this Ohio town, who the Republican accused of eating pets, share their concerns and fears ahead of the presidential election on Tuesday

There is only one object out of place in Jim Denis’ photography studio in Springfield, Ohio — a city that has been thrust into the national spotlight due to Donald Trump’s racist remarks about Haitian migrants. The 30-year-old Haitian learned to take portraits with YouTube tutorials and uses the studio to photograph families and pregnant women. On his desk rests a holster for a firearm, which he explains is kept in a safe at home. “I need to protect my family,” he says. “The neighborhood where we live is predominantly white, and you don’t know who hates you and who doesn’t. They don’t talk to me, so I have it just in case,” he adds in English, tucking the holster away in a drawer.

Denis’s profile starkly contrasts with the image Trump painted of Haitian migrants during the presidential debate in September that drew over 67 million viewers. In that debate, Trump falsely claimed that Haitians in Springfield were eating residents’ pets — an outrageous falsehood that has strained racial tensions. Fact-checking organizations traced this false allegation back to social media accounts affiliated with members of the Blood Tribe, a neo-Nazi group that had begun circulating the misinformation in early August.

Denis has lived in Springfield for five years. He grew up in Port-au-Prince and studied in the Dominican Republic, where he learned Spanish by watching Telemundo shows. About a decade ago, he emigrated to Florida, a common entry point for many Caribbeans; in fact, half of the country’s 700,000 Haitians reside there. He trained in Fort Myers to become an electronics technician and first heard about Ohio from his younger brother, who promised him that work would be easy to find in the state.

And so it was. Today he is the very image of a successful businessman. He owns three properties in the city, a studio and is an event promoter. However, his main income comes from repairing Amazon robots in the technology giant’s local warehouses, which are among the region’s largest employers.

“This was a very small town, and it can be worrying when so many people come to your community,” admits Denis, who lives in Springfield with his wife and two-year-old son. “They think that Haitians who come here want help from the government or to take advantage of it. Nobody asks you. If they see that you have a nice house, they think the government gave it to you!”

In September, Springfield authorities estimated that the Haitian population in the town ranged from 12,000 to 15,000. However, Obed Lamy, a Haitian documentary filmmaker working in the area, contests this figure, suggesting that a community of that size would be more visible in such a small town. In the wake of the Republican’s remarks, several families have either left or are planning to leave Springfield.

Adaptation problems

Elinor Fortune is already thinking about leaving. At 54 years old, with six children — all of them adults — he is one of the dozens of Haitians who arrived in the U.S. during Joe Biden’s term. He has been in the country for seven months and in Springfield for two. Before the U.S., he lived in Brazil, where he stayed for 11 years. He sold several of his belongings to undertake the journey north. “I don’t know why I came. The things I thought about the U.S. were not true. I found many difficulties, many calamities, many problems. It has been very complicated. My wife cries all the time,” he says.

Fortune — who has a work permit and has protection from deportation valid for two years — gets by distributing food for an app. And thanks to the safety net that the city’s 10 evangelical churches have woven to help Haitians. However, his outlook is grim as the presidential election approaches. “The things that Donald Trump says about us are very harmful to me and to any Haitian here in the United States,” Fortune says in Spanish. Once he manages to save enough money, he plans to return to South America.

On Friday morning, Fortune fills out a job application for Walmart on a computer, assisted by Michelet Delcine, a self-proclaimed community leader who owns several businesses aimed at supporting the community. Delcine immigrated to the United States as a teenager in the early 1980s. He lived in Florida until he was forced to relocate after losing his job during the pandemic. He has since found opportunities in Ohio, a Republican stronghold that Trump is expected to win easily on Election Day on Tuesday.

Trump’s remarks about Haitians has motivated Delcine to enter politics. He has found the courage to launch a campaign for the municipal commissioner position in 2025, where he aims to advocate for the rights of the Haitian community. As an evangelical pastor, Delcine acknowledges that many newcomers must make greater efforts to adapt.

“They need to learn about American culture. They do a lot of things that Americans don’t do,” Delcine says in his office, adding that one of the most pressing issues is for immigrants to understand traffic rules. “That way, they will cause fewer accidents. That’s the biggest complaint against us right now,” he adds.

Traffic accidents

Traffic accidents have become a focal point in the cultural clash within the city. Ohioans have voiced concerns that some immigrants drive without licenses and disregard traffic laws. This conflict escalated in late August when Hermanio Joseph, a 36-year-old Haitian, collided head-on with a school bus on the first day of school. Aiden Clark, an 11-year-old boy, lost his life when he was thrown from the bus’s windshield. Joseph only had a license issued in Mexico.

The issue has heightened tensions at council meetings, where residents express controversial opinions. “When we give people three minutes to speak and they start with, ‘I’m not racist, but...’ — when they use that phrase, they don’t know what it tries to cover up,” said the city’s mayor, Republican Rob Rue.

The contributions of the Haitian community in Springfield are evident. The small Adasa supermarket is filled with energy drinks and brands of basmati rice imported from Haiti. Customers can find yucca and plantains, staples of Caribbean cuisine, alongside bread shipped in from Florida. The aisles are bustling with Haitians shopping, and outside the store, a long line forms with people waiting to send money to the island, paying a commission of up to $10 for every $300 sent. All the signs in the store are in Creole.

The supermarket is operated by the Buitron brothers, two Mexican entrepreneurs. They are nervous about the media attention: some journalists have come to photograph their butcher shop. “We haven’t been selling meat for that long, and they’ve never asked us for it before,” Saul, one of the owners, admits. He quickly adds, “We do not agree at all with what is said about them; we do not agree with racism. They have always been excellent customers.” Business is going so well that the brothers opened a second store in Springfield just last weekend.

“After Trump, some people called me to ask if we had cats and dogs on the menu. I tried to be nice to them and read them some of the dishes we had,” says Rosema Jhuis, owner of the Haitian restaurant Rose Goute.

Jhuis, originally from Petit-Goâve, cooked traditional dishes for the community before deciding to open the restaurant in mid-2023. Today, he employs 10 Haitians in the kitchen, where they prepare goat stews, rice and beans with fried plantains. The day before the interview, Jhuis had the honor of hosting musician John Legend, who hails from Springfield. Legend recorded a message against hate during his visit to the restaurant.

Solidarity in the face of hatred

Many of the diners aren’t even locals; they’ve traveled long distances to express their disapproval of Trump’s remarks. One such diner is Jason Lockhart, originally from Alabama. His grandfather was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan, and his father had to win a discrimination lawsuit just to keep his job.

“A lot of people feel more comfortable making these kinds of racist comments now; it’s on the rise. The Springfield issue has gone from being about the border and immigration to being a completely racist narrative,” says Lockhart, a sales agent for dietary supplements who spends his free time educating others about racial history.

In early August, a dozen neo-Nazis marched through downtown Springfield, chanting racist slurs. Their faces obscured by ski masks as they waved swastika flags and carried rifles. Local authorities described the protest as “unfortunate” but said that it was protected under free speech and state law, which allows weapons to be carried in public.

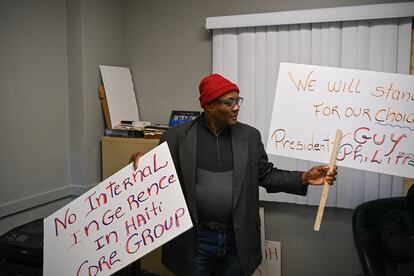

The reaction to that march was evident in the streets of the city just a few days later. The city’s religious leaders organized a demonstration in favor of unity, with dozens of people walking two miles to show the Haitian community that they are not alone. However, the turnout was not as big as expected.

“I’m not worried about hate groups or the KKK,” said Carl Ruby, a white pastor at a Catholic Church, at the October march. “What concerns me is the white moderate church that doesn’t get involved. I want to apologize for the lack of diversity. There are very large evangelical churches here, and I don’t see them standing with us. I’ll be honest: people from my congregation didn’t come, either. We have to do better,” Ruby told the predominantly Black audience.

He was followed by Mayor Rob Rue, who declared: “Hate has no home here.” That morning, a Black singer from an evangelical church sang alongside a Haitian pastor, a powerful moment of unity in a community shaken by Trump’s xenophobic rhetoric.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.