The deportation that thwarted Sara and Kinzie’s wedding plans

Sara, a Venezuelan immigrant, was arrested by federal agents as she left work in July. She unwittingly signed her own deportation order back to her country, and her partner, Kinzie, was powerless to stop it

Two men approached her. They surrounded her, shouted at her, and pinned her against a van.

“Please let me go!” she begged him in English. Sara fumbled for her phone with a free hand and dialed her girlfriend, Kinzie Morrow, putting the call on speaker.

“Get in the car!” they yelled. One of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents pointed his taser at her. Sara panicked and squirmed as she was handcuffed. The officer warned her that if she didn’t stop moving, he would use the taser.

Sara, who agreed to be interviewed on the condition that her last name would not be used due to fear of persecution, was walking to her car in the parking lot of her job when she was arrested by ICE on July 18. Like many immigrants, the 30-year-old Venezuelan woman worked multiple jobs to stay afloat and contribute to her community, but on Friday, July 18th, she was working in her main role as a baker and pastry designer at the Walmart in Centennial, Colorado.

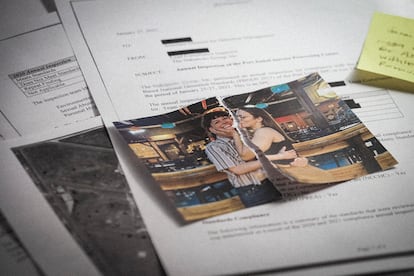

Sara was especially eager to leave her shift that afternoon. She intended to fly to Texas later that day so she could meet her partner Kinzie’s family for the first time. It was the next step in their plan to eventually get married — two days before they had moved in together. Six days earlier, they’d celebrated Sara’s 30th birthday together.

“I was ready to make my life with her,” Sara gushed. “I’m completely sure she was my person.” When she was arrested, she said it felt like her entire world was taken from her in seconds.

When Kinzie picked up the phone that Friday, Sara said that the police were there. Kinzie could hear the officer’s shouts from her end of the line. She surmized that they were ICE agents, and tried speaking to them directly, asking why Sara was being detained, and whether they had a warrant. The agents largely ignored her at first.

One of the officers eventually identified himself, telling Kinzie that the reason Sara was being taken was that she had failed to fill out a 1099 form, a tax document used to report income other than wages or salaries. “She’s an illegal,” he added.

But the reality is that Sara had a valid work visa and had submitted a 1099 form to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for another role as an independent contractor at DoorDash. She was in the country under humanitarian parole, a program that granted temporary residency to 500,000 immigrants from Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Venezuela. In May, the Supreme Court gave the Trump administration the authority to end this program, exposing its beneficiaries to sudden deportation.

Her arrest represents a scene that has become familiar across the country as part of Trump’s intensive immigration policy. Kinzie, who is a U.S. citizen, and her determination to find her girlfriend and avoid her deportation illustrates the difficult situation that faces thousands of families every day, while the administration intensifies its efforts to try and expel one million immigrants in the first year of the Republican president’s tenure.

A false promise

The ICE agent who arrested Sara handed her a sheet of paper later that day, once she was in custody at the federal agency’s local office in Centennial Colorado. She asked what it was for, and he replied that the form would allow her to get a lawyer. Sara was afraid. The paper was in English and she didn’t understand it completely, but the agent assured her that she would not be allowed legal representation if she didn’t sign the form, so she jotted her name down.

The paper, which was reviewed by EL PAÍS, was an expedited removal form. Sara had just unknowingly signed off on her own expulsion.

“There’s no such thing as a form you can sign to get yourself a lawyer. Period,” cautioned Karen Zwick, Director of Litigation at the National Immigrant Justice Center.

The Immigration and Nationality Act states that immigrants have a right to counsel as long as it’s at no expense to the government. In rare cases, one can be appointed a lawyer if they are accompanied by an immigrant child or deemed incompetent by a judge, but in the past few months, the Trump administration has attempted to cancel those programs as well.

“I think there is a great deal of misrepresentation, especially right now, happening in the context of immigration detention,” Zwick continued. In ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody, the expert added, officers will create storylines around what may or may not happen if detainees sign the indicated line.

“Sometimes those mysteries are, like, ‘you can go home if you sign this form,’ and people think that they’re talking about going home to wherever they were living in the United States,” when really, the officer is referring to their country of origin, and the migrant is signing an expedited deportation form that gives the government broader authority to expel them, Zwick commented.

While Sara was unknowingly signing off on her own removal, Kinzie followed the location tracker on her girlfriend’s phone, which had been confiscated, and arrived at the office where she had been detained. She was told that she wouldn’t be able to see Sara that night, or receive any information until she was transferred to the Aurora, Colorado ICE Processing Center.

The next morning, Kinzie spotted Sara in ICE’s Online Detainee Locator System in Aurora. Because it was a Saturday, there were no visiting hours. On Monday, July 21, both Kinzie and one of Sara’s relatives went to see her for the first time. Representatives at the center told them that they could not give them any information about why Sara had been detained. Immigration attorneys offices were closed on the weekend, and Kinzie knew that a lawyer would cost more money than the couple had.

Out of desperation, Kinzie turned to TikTok, pleading for financial and legal resources. “We’ve been reaching out to attorneys, we can’t get calls back,” Kinzie implored in her video. “I have no idea what to do,” she continued. “She’s done her taxes. She has done everything she is supposed to, and we still don’t know why she is being detained.”

Her video has since amassed over half a million views and thousands of comments. Through her new following, Kinzie found an ICE education organization and a lawyer. She created a GoFundMe page and anonymous donations began flooding in from people across the country.

At first, the couple felt both hopeful and grateful. Since the start of 2025, high-profile expulsions with no legal justification and mass deportations to countries like El Salvador, Venezuela, and Panama under the Trump Administration have captured Americans’ attention. Kinzie and Sara both recognized that not every migrant has the resources that they found through TikTok.

It did little to help. In the end, Sara was still deported. The expedited removal form that the Venezuelan woman unknowingly signed streamlined her deportation. The use of expedited removal, a mechanism through which a foreigner can be expelled without seeing an immigration judge, has expanded in scope since Trump returned to power.

“I will not stop fighting, I will see her again,” Kinzie appealed to her new TikTok audience, choking up in another video.

“We slept in the cold and chained up”

Their hands and feet were shackled with chains that climbed up their bodies and roped around their waists, Sara said. With a group of other detainees, she was flown from Colorado to Utah on the morning of August 4, then Utah to Arizona and Nevada, before finally landing in Texas that same evening. With each stop, the plane picked up more migrants.

When she arrived at the Port Isabel Detention Center in Los Fresnos, Texas, she was boarded onto a bus with other men and women. She could see other buses outside her window. “They left us on the bus all night,” she recalled. “We slept in the cold and chained up.”

The detainees became desperate. The men started banging on the sides of the bus and shouting — they had not been allowed to use the bathroom all night, and they were still shackled.

Once Sara was inside, she was shuttled into a crowded room. “I was there for three days, without hygiene, without clothes. We slept on the floor.” There was no access to a telephone, she added and little access to medication for those who needed it.

While newly erected immigration detention centers like Alligator Alcatraz in Florida have gained attention in recent weeks for complaints about inhumane conditions, some previously existing facilities like Port Isabel have gone largely unreported on.

Detainees at Port Isabel are housed in four nearly identical housing units. By comparing satellite images to records of the number of beds in each unit, EL PAÍS found that each detainee has around 21 square feet of living space, which is about the size of a large pantry. By comparison, that’s almost four times what would legally be considered “overcrowding” in a New York City apartment.

That’s only when the facility is at capacity. The maximum population count for at least one day in 2025 at Port Isabel was 103 people over its contractual capacity, according to TRAC, a nonpartisan organization at Syracuse University that tracks overcrowding in detention centers.

“In that whole entire three day period while she was in Texas, they [ICE] didn’t update the website,” Kinzie said in an interview. So for her, Sara was missing. Kinzie turned again to TikTok to inquire about flight tracking resources, and got in touch with a flight-tracking hobbyist who was able to follow part of Sara’s journey. While he was helpful, and occasionally correct, it was difficult to follow her.

Since mid-May, domestic transfer flights increased by 65% compared to the average of the prior six months, according to data collected by Thomas Cartwright, a member of the immigration advocacy group, Witness at the Border, who independently tracks ICE flights. Those domestic transfers, like the ones Sara was subjected to, make it more difficult for lawyers to keep track of their clients facing deportation — and to help them defend themselves.

From the center in Texas, Sara flew to Honduras and eventually arrived as a deportee in Venezuela, where she remains.

Stranded in different countries

“That’s the more difficult part,” Kinzie said. “Not knowing how to really do life without her anymore.”

Kinzie and Sara have decided to reunite in a place outside of the United States. But as two women, they face an additional obstacle — finding a new home that is conducive to their LGBTQ+ status. They cannot move to Venezuela, which is considered a hostile country for the queer community.

The pair has considered Canada and Mexico, two countries nearby where gay marriage is legal. “I just want us to be safe wherever we go,” Kinzie maintained.

Only a few weeks ago, Kinzie never would’ve believed that Sara was in danger of being deported, given how hard she worked and how many steps she had taken to live in the United States legally. Now, they are coordinating from afar to sell most of their belongings to afford a permanent relocation together.

However, there was a bittersweet silver lining for Kinzie: the social media community she has built in a matter of weeks. She believes that her videos have shown more people how ICE is carrying out President Trump’s campaign of mass detentions and deportations. Sara agrees: “I hope my voice is heard to defend the rights of many people.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.