A roof over their head, English lessons and job training: Denver offers another model for migrants

After receiving 42,000 people bused in by Texas and spending $72 million to shelter them, Colorado’s capital is shifting its focus to a program that integrates asylum seekers into the community as soon as they receive their work permits

The memory of Denver the way it was nine months ago seems like something from another world. In mid-January 2024, the capital of the state of Colorado had reached peak occupancy at its makeshift temporary migrant shelters, which were holding 5,200 people. Nearly all of them were asylum seekers sent by bus from Texas by Governor Greg Abbott, and who were sleeping in hotel rooms paid for by the city. On the streets, entire families expelled from the shelter system for reaching the maximum time limit were reported to be spending the freezing winter nights at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, under bridges, and lining up for hours to get a hot meal.

Mayor Mike Johnston, with the city’s accounts in the red, asked the federal government for help several times. There was no response. Faced with silence and a municipal expenditure of $72 million since the end of 2022 to care for 42,000 migrants, he and his team decided that something had to change. So they devised a new program focused on long-term integration.

In the spring, while Chicago and New York were announcing new and stricter time limits for staying in shelters, Denver proposed almost the opposite: full and continuous support for six months, the time it takes to get approval for an asylum application and obtain a work permit. Now, with the new program in operation since late June and at full capacity, with 865 beneficiaries, including 215 families, and also with new migrant arrivals at a minimum due to the implementation of Joe Biden’s executive order to limit illegal border crossings, the city is a different place.

Sarah Plastino, director of the new program, explains that “the goal of the program came from the fact that a large number of people were leaving shelters and entering our communities here in Denver. We knew we needed a program that would specifically support those people who did not yet qualify for a work permit and needed to apply for asylum. So we designed this to capitalize on the six-month waiting period to train those who were waiting for their work permit and provide a large number of people with stability.”

First, they decided that instead of housing people and families in hotel rooms night after night, which was extremely expensive, they would be placed in permanent housing for six months. This is cheaper for the city, and it also gives the beneficiaries more autonomy. In partnership with non-governmental organizations, they assigned apartments and houses available on the regular market, according to the size of the families and the area where the children were already attending school. Using the same logic, they began to provide food and vouchers to prepare meals at home, which is also much more economically efficient for the city than providing food through restaurants or contractors. Also, to make it easier for the migrants to move around and communicate, those who joined the program were given mobile phones, SIM cards and public transit passes.

These foundations provide stability and generate a very different relationship with the authorities. Plastino likes to tell the story of how she recently put a migrant in touch with the police because she needed help with a delicate security issue. “She probably wouldn’t otherwise have felt comfortable enough to trust me and then talk to the police,” she reflects.

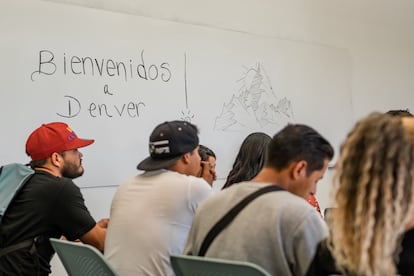

But the program has a long-term vision above all. While minors are legally enrolled in school as soon as they arrive, adults had to wait six months, unable to perform any paid legal activity until they received a work permit. Now, under the program and in alliance with the Workers’ Center, a city organization dedicated to the training and professional development of the working class, there are English lessons for migrants and job training in the areas where there is the greatest demand: construction, hospitality, and caregiving. In addition, the organization is in direct contact with potential employers and it is expected that the migrants will get good jobs as soon as they receive their paperwork.

This was already something that the Workers’ Center did independently, but by collaborating with the city the operation has grown immensely, says Mayra Juárez-Denis, executive director of the organization. “The city saw what we had done and was very impressed. We had limited resources… Now they are referring these participants to us and it’s like the same program we were running, but on steroids, because we have twice as many resources, more collaborators and more interest from companies, which are in contact with the city’s Department of Economy, to find jobs for people beforehand. That collaboration is very powerful.”

They are committed to training at least 500 people this year. The plan has several distinct stages. The first, which is now ending, focuses on the basics, mainly English language, computer skills and learning about the culture, to facilitate assimilation into a new society. The second, which is just beginning, is the vocational stage, aimed at preparing immigrants for the jobs that are available.

As an immigrant herself from Monterrey, Mexico, Juárez-Denis hopes that this program will demonstrate “the power of our institutions, not just government institutions, responding to the needs of the community.” She says that this way, a chain of solidarity and support is cultivated that strengthens the social fabric. She has already seen this in action: a family of migrants who “literally arrived with a backpack” and now, after finding employment, can also teach others.

For Plastino, the program is a source of pride after months of hard work to make it a reality. “It is designed to benefit the individual, but also industries where there is a shortage of workers. It is very strategic,” she says, adding that she would like to make it a model to follow by showing that even on a smaller scale it is possible to provide effective solutions to complicated problems.

However, the basis for the program’s success at the moment depends on border crossings remaining very low and, therefore, new arrivals in Denver being practically on hold. Throughout the months of July and August, Texas did not bus any more migrants to so-called sanctuary cities, and the handful of new immigrants who arrived in the capital of Colorado have been the recipients of a basic program that provides shelter and food; but for just a few days before facilitating their transfer to someplace else where they can be cared for by relatives or friends.

In the event that migrant arrivals spike again, Plastino says they are prepared and have redesigned the reception system based on lessons learned during the most critical period, although she does not provide details. In any case, the most important lesson is that one must be flexible and adapt to the specific needs of each moment, she stresses. In the current context, that means a comprehensive and long-term support program to facilitate the social and labor integration of the migrants who now call Denver home.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.