TikTokers against Washington: ‘If they ban TikTok in the US, they will destroy the American dream’

Users of the video-editing app are on the warpath after the House of Representatives approved a bill that would force ByteDance to sell the social network to a U.S. company

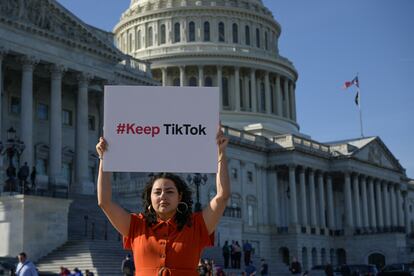

In addition to the usual tribe of lobbyists and other merchants of influence that swarm around Washington, last week saw a group of TikTokers protest outside the Capitol. Giovanna González — who has 200,000 followers on TikTok — was among the group. Last Tuesday, she met with members of Congress to try to get them to change their minds about new rules to ban TikTok in the United States. According to González, “those old white boomers want to ban” a tool that has allowed her to turn her “passion for finance education into a full-time job as a content creator and paid speaker.”

González was not successful: the next day the House of Representatives took the first step to force ByteDance, the Chinese parent company of TikTok, to sell the social media platform to an American company. If it does not do this, it will be blocked from the app stores in the United States, where 170 million — half the population — has a TikTok account. The move can also be seen as a challenge to China that will fuel the growing commercial and diplomatic tensions between Washington and Beijing.

Despite its popularity, few issues in Washington have achieved so much consensus in the most divided House of Representatives in memory. The measure was approved with 352 votes in favor and 65 against. In another sign of TikTok’s enormous influence, members of Congress received calls from TikTokers all throughout last week: the company had advised users on how it could send complaints to their corresponding representative.

Now that the law is on its way in the Senate — where it is not clear whether it will be approved — the company went on the attack again. On Thursday, the CEO of TikTok, Shou Zi Chew, visited Capitol Hill. “There’s a lot of noise,” he said. “I haven’t heard exactly what we’ve done that is wrong.” The next day, the company sent another notice: “Tell your Senator how important TikTok is to you. Ask them to vote no on the TikTok ban.” This is not the first time that a tech company has tried to pressure U.S. lawmakers by calling on its users, but none have ever campaigned so aggressively.

U.S. President Joe Biden has warned that he will sign the bill into law if it finally lands on his table. Although his re-election campaign has opened a TikTok account to reach Generation Z voters, the president agrees with cybersecurity experts, who point out that ByteDance is obliged under the Chinese espionage law to share its users’ data with Beijing authorities if they request it. Experts also warn that the addictive tool could contribute to misinformation and influence American public opinion ahead of the November election. And that worries the intelligence services, as the directors of the FBI and the CIA made clear this past week in the Senate.

“So far Congressional critics of TikTok have offered no real examples of how TikTok is a threat to national security. The personal data provided willingly by TikTok users, particularly in personal videos, does not appear to constitute anything resembling a national security threat,” Paul Triolo, one of the leading experts on the technological struggle between China and the United States, says in an email. “TikTok has also already taken major steps to control access to US customer user data via Project Texas, with the data hosted by Oracle in US based data centers. The malign influence argument is also dubious, as the vast majority of content viewed by TikTok users is user generated, and what they see via the recommendation algorithm is what they prefer to see. There is no evidence that the Chinese government is interested in or capable of forcing Bytedance and TikTok to alter the way the algorithm works, and in any case, this would be obvious to users.

ByteDance has repeatedly denied that it shares its data with Chinese authorities. In its defense, the company has claimed the ban is a violation of freedom of expression (an argument shared by prominent civil rights associations) and would take a heavy economic toll on users — people like Paul Tran and Lynda Truong, who run a cosmetic company (@loveandpebble, 138,000 followers), which owes “90%” of its income to the platform. “We’re not just on TikTok, we thrive on TikTok. If they pass this bill, they will be destroying the American dream,” says Tran.

The list of the 65 members of Congress who voted against the bill (50 Democrats and 15 Republicans) is a curious list of strange bedfellows: a mix of more progressive lawmakers such as Pramila Jayapal and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and members of Trumpism’s praetorian guard, from Matt Gaetz to Marjorie Taylor Greene. The youngest member of the Chamber, Maxwell Alejandro Frost, 27, also voted against the bill.

The voice of Generation Z

Frost is the voice of Generation Z on Capitol Hill, a group of voters that the parties risk losing with the TikTok ban. And not just them: according to the Pew Research Center, 72% of Americans agree that there needs to be more government regulation on tech companies’ use of data, an AP survey in February, found that just 31%. of U.S. adults are in favor of a TikTok ban.

At an event at Georgetown University on Thursday, influential tech journalist Kara Swisher tried to reassure students. “Kids, your TikTok’s not going away, FYI,” Swisher said. “It’s worth too much. None of these rich people are going to let that die. It’s whether the Chinese government, which has been involved in every Chinese company, is going to be able to have this access.”

Swisher, however, is more concerned about TikTok’s propaganda power than its threat to national security. The app is already banned at almost all levels of the U.S. government. “It is as if we gave ownership of all the cable television networks to a foreign government: the Chinese one, to be exact,” she warned. “Or worse, because TikTok has more power than CNN, MSNBC and Fox combined.”

If the law goes ahead, ByteDance is confident that it could still be overturned by the U.S. courts, as happened when Donald Trump tried unsuccessfully in 2020 to get his hands on the Chinese technology company. But that effort was not entirely in vain: it forced ByteDance to store the data of American users on servers located in Texas and controlled by the technology giant Oracle.

Trump is now against banning TikTok because he argues that it will give Meta — a tech company he calls “the enemy of the people” — more power. Recently, U.S. media has shed more light on Trump’s change of heart: it turns out that Jeff Yass — one of the most powerful donors of his campaign — owns 15% of ByteDance. And the Republican candidate for the White House is considering naming him secretary of the Treasury if he wins the election in November.

Under the bill, TikTik would have six months to find a U.S. buyer. Some of the biggest names in Silicon Valley are rumored to be interested. Steven Munchin, Trump’s former Treasury secretary, announced the day after the House vote that he is gathering a group of investors to bid. According to CB Insights, ByteDance was valued in December at $225 billion, but the price of TikTok — known as Douyin in China — is not yet known, although some put it at $84 billion.

And the algorithm?

It’s not clear how much it will sell for, nor what exactly will be sold. Swisher is convinced that if ByteDance finally sells, it will keep TikTok’s greatest secret weapon: the algorithm that has transformed internet culture and keeps users wanting more. In order to sell the algorithm, it needs permission from Beijing.

The bill is now moving to the Senate, but debate on its passage is expected to drag on, as Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has not yet decided whether to force a vote. The bill would also requite the new owner of TikTok to cut any “operational relationship” with ByteDance.

“It is unlikely that the Chinese government will approve the transfer or licensing of that artificial intelligence algorithm,” says Triolo. “Also, no one is going to pay what TikTok costs without having access to that secret. And it's also unclear how that technology could be transferred, even if Beijing approved such a deal, because the engineers and developers are in China. Recreating the algorithm would be difficult, time-consuming and there would be significant uncertainty around this process, which would worry investors.”

If a U.S. company were still to buy it under these conditions — an operation that The New York Times columnist David E. Sanger compared to “acquiring a Ferrari without its famous engine” — the other big question is whether TikTokers will be faithful to the “made in America” version of the social platform or whether it will turn into a shiny husk of itself.

It is also not clear how the new algorithm would affect the more than seven million companies that, according to TikTok data, do business on the video-sharing app. On Friday, a TikTok spokesperson sent this newspaper a link to the profile of Carlos Eduardo Espina, one of the content creators who came to Washington to pressure lawmakers against supporting the ban. In a featured video on his profile, he explains that he made $770,000 on TikTok in 2023. In another clip, with the Capitol in the background, he warns his 8.8 million followers that the sale requirements would force TikTok to change “drastically.” “It wouldn’t be the platform we know and love,” he argues.

TikTok did not, however, respond to EL PAÍS’s request for a comment regarding the campaign to pressure senators. The company’s move to encourage TikTokers to flood their representatives’ phone lines with angry calls has fueled further criticism of the app. Critics see it as the definitive (and perhaps unintentional) demonstration of TikTok’s enormous ability to influence American politics in one of its most decisive years in recent history.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.