Furby Alert: When a toy frightened the US intelligence services

It may make us laugh, but perhaps the overreaction by the NSA, which has once again come to light through the publication of thousands of emails, was not so different from our current attitude towards technological change

In early 1997, Dave Hampton and Caleb Chung, two product developers who had met while working at Mattel, attended the International Toy Fair in New York. There they saw for the first time an artifact that impressed them. It was the Tamagotchi, then a new virtual pet that the Japanese inventor Aki Maita had developed and Bandai had begun to market. The concept behind that toy seemed brilliant to them. However, they found a problem that seemed fundamental: you couldn’t hug or pet your Tamagotchi.

After that discovery, Hampton returned to his workshop and began to think about a new toy that, taking the Japanese invention as a starting point, would be a little easier to love. The name he gave to the new invention was Furball, although he soon shortened it to Furby. “I started a script, like, if you rub his back, he’ll purr,” he explained to The New York Times a few years later. He also created a language for the creature, Furbish: it was a mix of all the languages Hampton had learned during his years of service in the U.S. Navy. Among the toy’s strange vocabulary, it is possible to trace words that come from Japanese, Thai, Chinese and Hebrew.

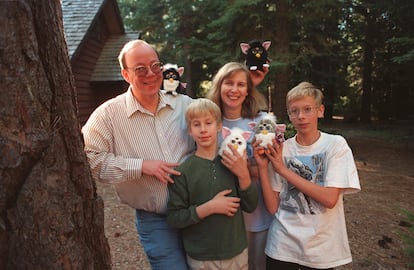

With Chung’s help and a bunch of cables, sensors and simple circuits, they shaped the Furby’s guts, which they then covered with a colorful furry animal — just as its name promised — with huge round eyes and a yellow beak. That first prototype, a little smaller than the final product and much more unsightly, can be seen in a video interview that Chung gave in 2014.

Everything moved very quickly after that. Tiger Electronics, a subsidiary of the multinational Hasbro, bought the patent and the product went on sale in October 1998, a few months before Christmas. After a powerful advertising campaign that highlighted the novelty of the new toy, Furby was presented to the public at the famous New York toy store FAO Schwarz, the one where Tom Hanks danced on a giant piano in the movie Big. The launch could be described as a total success, but that would definitely be falling short. At the end of the first week of the exhibition at FAO Schwarz, orders already amounted to 35,000 units. An impressive figure that came to nothing in the following three months, as the figure skyrocketed to 1.8 million units sold. In 1999, sales reached 14 million.

Although it would be daring to venture to say what the secret of its success was, what is clear is that its creators were wise enough to combine toys that had been children’s favorites for years, such as teddy bears and talking dolls, and update them for the 21st century. In some way, Furby satisfied a certain need, among children and parents, about the future. The year 2000 was close at hand and, although everything was quite similar to the way it had always been, the democratization of the internet had made us dream of a new present. Furby, rudimentary as it was, seemed to have what was beginning to be called “artificial intelligence.” Furthermore, it allowed us to connect and feel a kind of intimacy with a technology that the Tamagotchi had already outlined in a more distant form, sending children and their parents into the future. It was the closest thing you could find to one of those robots from sci-fi movies, but you could also hug it, it was adorable, fun and it only cost $35.

Furby and the National Security Agency

The story of Furby’s launch is fascinating on its own. But perhaps it is even a little more so if we pay attention to a curious incident that occurred during Christmas 1998, involving the National Security Agency (NSA).

The first news reports came out on January 12, 1999, in The Washington Post. The article, written in a shamelessly humorous tone and titled “A Toy Story of Hairy Espionage,” explained how, due to all the rumors and exaggerations that had been circulated about the capabilities of Furbys — especially that they could repeat what they heard — the NSA had decided to launch a Furby Alert among its employees and prohibit them from bringing the toy to work. The newspaper cited an alleged memo that had been circulated internally at the agency that read: “Personally owned photographic, video and audio recording equipment are prohibited items. This includes toys, such as Furbys, with built-in recorders that repeat the audio with synthesized sound to mimic the original signal. We are prohibited from introducing these items into NSA spaces. Those who have should contact their Staff Security Officer for guidance.”

The Post article continued: “It’s hard to imagine them divulging state secrets, but who knows more about pulling in what it hears than the NSA, which intercepts electronic communications around the world using satellites and other highly classified means. NSA officials were worried, said one Capitol Hill source monitoring the intelligence community, ‘that people would take them home and they’d start talking classified.’”

Tiger Electronics was forced to come forward to confirm that the Furbys did not have recording systems nor were they capable of repeating any type of information. Although it seemed that little by little they were learning to speak, it was all an illusion: they began speaking exclusively in their own made-up language, and were programmed so that, as the days went by, they would say more and more words in English or any other language they were programmed in. That is to say, they didn’t actually learn anything, they only gave the impression of learning.

Recently, this curious confusion came to light again due to a Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request by an anonymous citizen who goes by the user name @dakotathekat on the social platform X. In compliance with the law, the NSA sent this individual a large amount of information containing all the conversations that NSA officers had regarding the case. There were chains of emails filled with speculation and very little information about the artificial intelligence of the dolls, their communication and recording capabilities. The exchanges do not exactly leave employees in a very good light, instead evidencing their mistrust and fear.

I have acquired the fabled NSA "FURBIE ALERT" memo.

— (da)kota/the/Kæt (@dakotathekat) January 22, 2024

I have a significant amount of documentation that came back on an FOIA and I'll be scanning it in the coming days.

Stay tuned. pic.twitter.com/Fyo04dm4Oo

The documents end with a message in which an official demands that his colleagues stop speculating on the subject immediately. Perhaps out of fear that the agency would be made to look ridiculous if, at some point in the future, these conversations ever came to light, as they finally have.

An ancestral fear of technological innovation

After 25 years, this fear of a toy displayed by the world’s most important security agency may seem ridiculous and unfounded. And maybe it was. However, the fear of technological innovation, or technophobia, has been with us for centuries. Although there are cases in the Middle Ages, such as the people who rejected the printing press in the 15th century, perhaps the first important example was the English Luddites: they were a group of anti-technology workers who, between 1811 and 1816, denounced that the new steam engines were taking away their jobs. In the middle of the British Industrial Revolution, they carried out sabotage actions in industrial or agricultural machines and workshops.

The rapid technological progress of the 19th and 20th centuries only increased the cases of technophobia. Virtually every major technological advance has had its detractors: from the railway to electricity, the telephone, automobiles, television and the uses of radioactivity.

This is ground that has always been very fertile for the creation of fiction. An early example of this is Frankenstein, the novel by Mary Shelley, but there are many more, especially in the world of cinema: from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to The Omega Man, Blade Runner, Terminator, Matrix and WALL-E.

But technophobia is perhaps currently experiencing its golden age due to new scientific advances that seem to call into question many of the pillars of our civilization that we considered immovable. This is the case, of course, of artificial intelligence and its possible effects at work. A fear that connects us directly with the Luddites, but also with the Furby alert. It is easy to laugh at a bunch of clueless individuals who, back in 1999, feared that a new hoarse-voiced doll might be able to destabilize the Clinton administration. But you could say that the Furby alert was nothing more than another chapter, perhaps one of the funniest, in our long relationship with technophobia.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.