The 2001 anthrax attacks explained: Everything you need to know

The FBI identified Bruce Edwards Ivins as the sole perpetrator of the anthrax attacks. However, the case remains controversial, with experts and colleagues expressing doubts

Beginning on September 18, 2001 —just one week after the September 11 terrorist attacks in the U.S.— letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to several news media offices and government officials, resulting in the deaths of five people and 17 infections. Although the Bush administration quickly blamed al-Qaeda —the organization behind 9/11— and Iraq for the attacks, the FBI declared American microbiologist Bruce Edwards Ivins as the sole perpetrator. However, a scientific report cast doubt on that conclusion, and some believe there may have been more people involved.

What is anthrax?

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, which manifests in four forms: cutaneous, pulmonary, intestinal, and injection. It can spread through contact with the bacterium’s spores, often found in infected animals or animal products. Symptoms can appear between one day and more than two months after contracting the infection. In the cutaneous form, a small blister with surrounding swelling turns into a painless ulcer with a black center. Pulmonary anthrax manifests itself with fever, chest pain, and breathing issues, while the intestinal form causes diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. In the injection form, it may lead to fever and an abscess at the injection site.

According to the CDC, anthrax was first identified in 1752, and in 1769, it had been described in historical accounts. Anthrax vaccinations have been available in the U.S. since the 1950s and are recommended for people at risk of infection or in areas with previous infections.

The anthrax attacks

The 2001 anthrax attacks occurred in two sets of letters containing anthrax. The first set, postmarked Trenton, New Jersey, on September 18, 2001, was sent to ABC News, CBS News, NBC News, the New York Post (all located in New York City), and the National Enquirer at American Media, Inc. in Boca Raton, Florida.

The first known victim was Robert Stevens, a photojournalist who worked at the Sun tabloid, also published by AMI. He died on October 5, 2001, four days after experiencing symptoms like vomiting and shortness of breath. The letter was never found, but three individuals at ABC, CBS, and AMI became infected with anthrax.

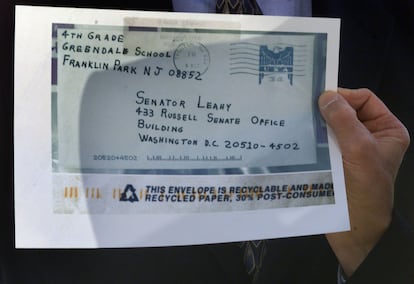

The second set of letters, dated October 9, were addressed to two U.S. Senators: Tom Daschle of South Dakota, the Senate majority leader at the time, and Patrick Leahy of Vermont, head of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The letter addressed to Daschle was opened by an aide, Grant Leslie, on October 15, prompting the shutdown of the government mail service. The one addressed to Leahy was found in an impounded mailbag on November 16 because of a ZIP code misreading. David Hose, who worked at the annex, contracted anthrax.

The material found in the media letters was described as “clumped coarse brown granular material, similar in appearance to dog food,” according to a scientific examination. The Senate letters contained a more potent, highly refined dry powder consisting of about one gram of nearly pure spores. Although some reports initially claimed that the powders were “weaponized” with silica, bioweapons experts later rebuked this claim after analyzing the anthrax used in the attacks.

The letters were copied using a copy machine; the originals were never found. Both are dated September 11 in a possible reference to 9/11.

The media letters contained the following note:

“09-11-01

THIS IS NEXT

TAKE PENICILLIN NOW

DEATH TO AMERICA

DEATH TO ISRAEL

ALLAH IS GREAT”

The Senate note read:

“09-11-01

YOU CANNOT STOP US.

WE HAVE THIS ANTHRAX.

YOU DIE NOW.

ARE YOU AFRAID?

DEATH TO AMERICA.

DEATH TO ISRAEL.

ALLAH IS GREAT.”

The references to Allah and “Death to America” appeared to link the letters to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Immediately after the attacks, FBI Director Robert Mueller faced pressure from White House officials to publicly blame al-Qaeda without evidence. President George Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney also mentioned the possibility of a link between the attack and al-Qaeda.

Who was responsible?

In October 2001, it became known that the strain of anthrax used in the attacks was the Ames strain, isolated in Texas in 1981. Molecular biologist Barbara Hatch Rosenberg suggested that the mailings might be the work of a “rogue CIA agent” and provided the FBI with a name of the “most likely” person involved, leading to an investigation into Steven Hatfill, an American physician, pathologist, and biological weapons expert. Hatfill was considered a “person of interest,” and his apartment was searched by the FBI on June 25, 2002. Hatfill denied involvement and later filed a lawsuit against the FBI, which was settled with a $4.6 million annuity in 2008. He was officially exonerated of involvement in the attacks. The Justice Department later identified military scientist Bruce Edwards Ivins as the sole perpetrator.

Ivins, a microbiologist at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick, Maryland, had been involved in anthrax research, developing vaccines and treatments for anthrax infections. He came under suspicion in 2008 after a lengthy FBI investigation due to his access to anthrax at his workplace, his expertise in microbiology, and inconsistencies in his statements and unusual behavior. The FBI also discovered that Ivins had mental health issues, a history of threats, and detailed homicidal plans shared with a social worker who treated him.

Ivins died by suicide on July 29, 2008. Eight days later, the FBI and the DOJ formally announced that the Government had concluded that Ivins was likely solely responsible for the attacks. On February 19, 2010, the FBI released a 92-page summary of evidence against Ivins and closed the investigation.

Despite the FBI’s conclusion, some senior microbiologists, the widow of one of the victims, and Patrick Leahy, who was among the targets, have contested it.

The FBI later requested a panel from the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to review its scientific work on the case. On May 15, 2011, the panel concluded that “the bureau overstated the strength of genetic analysis linking the mailed anthrax to a supply kept by Bruce E. Ivins.” It also stated that “it is not possible to reach a definitive conclusion about the origins of the B. anthracis in the mailings based on the available scientific evidence.”

As a result of the attacks, five people died, and 17 were injured. Several victims reported lingering health problems years after the attack, and no further investigation into the case has been conducted.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.