He lost a son, did battle with Trump and is now fighting cancer: The resistance of Congressman Jamie Raskin

The Democratic representative, who experienced the Capitol riots just days after his son committed suicide, spoke with EL PAÍS about his participation in the committee to investigate the events of January 6, 2021. He vows that his battle with illness will not compromise his ‘struggle to defend democracy’

This interview was originally meant to take place on December 28, 2022, one week after Congressman Jamie Raskin – a Democrat from Maryland – read out a statement on behalf of all nine members of the bipartisan congressional committee that investigated the assault on the Capitol, which took place just over two years ago, on January 6, 2021.

On December 19, the panel agreed to refer former president Donald Trump and others to the Justice Department for potential criminal charges, including the charge of inciting an insurrection. However, that same day, it was announced that Raskin – one of Washington’s most charismatic politicians – is suffering from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. This cancer, which is considered to be “serious but curable” by oncologists, became national news, forcing his meeting with EL PAÍS to be delayed.

Since then, Raskin has undergone the first of six chemotherapy sessions.

“I’m hanging tough. The doctors are very optimistic about it. I’m very optimistic about it,” he says.

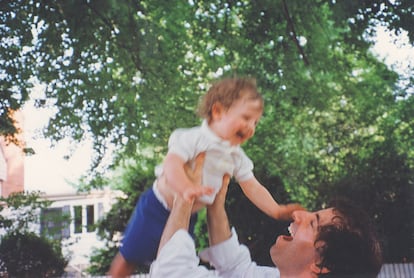

In addition to this difficult medical situation, the congressman has recently commemorated two terrible anniversaries. On December 31, 2022, it was two years since the death of his son, Tommy Raskin, who committed suicide at the age of 25 while suffering from depression aggravated by the Covid pandemic. And, on January 6, two years had also passed since rioters stormed the Capitol building. On that day, Raskin, along with hundreds of other congresspeople, had to flee through the halls of the legislative branch to save themselves from a violent mob.

Both of these “insurmountable traumas” – mourning and insurrection – are the backbone of Raskin’s memoir, Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy. The book, published by HarperCollins in January of 2022, is a mixture of a political treatise and personal memories from the months in which a man lost a son, was about to lose a democracy and became a figure of international prominence by leading – at the request of then-speaker Nancy Pelosi – the second, unsuccessful impeachment against Trump.

Raskin’s prominent role as a member of the committee that investigated the attack on the Capitol made him a key witness to the recent history of the United States. He likes to play this down.

“History sometimes decides for you.” The past few years of his life are certainly proof of this.

Raskin, 60, spoke to EL PAÍS last Saturday, from his home in Takoma Park – a suburb of Washington, DC – in Montgomery County, Maryland. He wasn’t wearing his usual dark suit and tie, but rather, dressed in comfortable clothes, with a backwards baseball cap. He apologized that the interview was over Zoom; the doctors, he explained, have advised him to avoid contact with people as much as possible. “I’m immunocompromised.”

He does not plan, however, to let the disease keep him from his legislative work and his “struggle to defend democracy.” He demonstrated this during the first week of the new session of Congress, in which – for the first time in four years – the House of Representatives is controlled by the Republicans, who have a tiny majority.

The election of Speaker Kevin McCarthy, a Republican from California, resulted in an embarrassing spectacle, with the process being hijacked by 21 far-right lawmakers who forced McCarthy to go through 15 rounds of voting before allowing him to be sworn in.

Raskin – who taught constitutional law before entering politics – didn’t miss a single one of those votes. He spent those days in a “little conference room” adjacent to the chamber.

“I was not able to hang out, but I spent a lot more time tweeting,” he recalls. “It’s tough for me as a politician, most of us are compulsive extroverts.”

For an avid student of US history like Raskin, the rounds of failure were historic for the wrong reason: never in a century had a party been unable to elect its own leader right off the bat.

“The extremist right-wing faction of the Republican Party called the Freedom Caucus is basically able to hold their whole Republican majority hostage until they get everything they want. And that’s what we saw happen,” Raskin notes. “We saw McCarthy cave in to everything they were asking for: The promise to create a new committee for attacking government investigations, which I call the Insurrection Protection Committee, because they’re basically trying to insulate themselves from investigation and prosecution for their role in January 6.”

“They’ve been very clear that their plans for this Congress is just to try to conduct a series of hearings about scandals du jour and they hope to engage in character assassination of Joe Biden’s administration,” he adds.

One of the first controversies stirred up by conservatives this year is the discovery of classified papers that were in Biden’s possession, from the two terms that he served as Barack Obama’s vice president (2009-2017). They were found by Biden’s lawyers at a private office in Washington and at the president’s private residence in Wilmington, Delaware. The attorneys brought their discovery to the attention of the Department of Justice and handed them over to the National Archives.

Republican Congressman James Comer – chairman of the House Oversight and Accountability Committee – has ordered a House inquiry, despite Attorney General Merrick Garland appointing a conservative special counsel with the same mission.

Raskin acknowledges that it’s “unfortunate” that Biden had “that relative handful of documents.” He considers that handing them over “immediately” to the authorities was “the right thing to do.” But he doesn’t believe the intervention of Congress in the matter is necessary.

When asked if the attorney general’s decision equates the Biden case with the top-secret papers that the FBI found in Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida, he replies: “Obviously, it’s more serious in Trump’s case where there were thousands of documents missing and he defiantly fought to keep them secret. And they were in a very public place, not locked up in an office, but rather at a hotel [a wing of Mar-a-Lago].”

“I don’t see why we need to conduct a legislative investigation when there is a special counsel operating. That’s what gives this much more the look of a show trial. We conducted a year and a half investigation into the assaults on Congress and the democracy on January 6, because there was no outside commission doing it.”

To fulfill that mission, the January 6 Commission interviewed around 1,000 people and reviewed more than 100,000 documents. In addition, the members shared their conclusions with the American public via televised hearings to “teach the people the consequences of setting yourself up against the constitutional order and against the government.”

“Democracy is under assault all over the world. This is a global phenomenon we’re dealing with,” the congressman explains, pointing to the recent assault on Brazil’s National Congress, Supreme Court and presidential palace by thousands of supporters of former president Jair Bolsonaro.

Raskin was not surprised when this took place. “I‘ve had a visitation of human rights groups and lawyers, groups and legislators from Brazil several months ago, and they were predicting that Bolsonaro would attempt the exact same thing Trump had done, and Bolsonaro’s son was in Washington on January 6. Steve Bannon, who is the key philosopher of the extreme right wing movements in America, has been in close contact with the Bolsonaro forces in Brazil. It was a very predictable event actually.”

The January 6 Commission’s final recommendations – which included charging Trump with four crimes and banning him from seeking public office again – could only be that: recommendations. But Raskin is confident that the US Department of Justice will have taken note.

“They have done a very good job in prosecuting hundreds of participants in the violence on January 6 [...] I would be surprised if Trump wasn’t prosecuted.”

For now, though, Trump has announced his third candidacy for the White House, two years in advance. This will hinder many of the legal cases he has pending across the country.

“Now, there are some people like Governor [Ron] DeSantis in Florida and Governor [Glenn] Youngkin [in Virginia] who would like to take him on,” the congressman admits. “But Trump’s still the leading figure in the party. And in the same way that he refused to accept the idea that he had lost the 2020 election, he will refuse to accept the idea that he has lost the primary fight in the 2024 election and he will try to run as an independent.”

This makes Raskin uneasy. “Trump unleashed very sinister and fascist forces in the country. And just as they attacked the US Capitol, in January of 2021, they could also proceed to attack state capitols and school boards and other public institutions around the country.”

For Raskin, such a threat is more of a personal matter than a political concern. In Unthinkable, he relates the suicide of his son with Trump’s “lethal recklessness and incompetence in confronting the pandemic took place against the background of an already violent, hateful, and polarized culture he was bringing into existence.”

“The staggering public mental and emotional health crisis of the Trump years hit young people hard, and it hit people already struggling with a mental illness like a tornado. Tommy was in both groups,” writes Raskin.

In the interview, Rasking highlighted some of the progress that has been made since his family’s loss, such as increases in public funds for programs to combat mental illness, or the opening of a suicide prevention hotline.

“On the other hand,” warns the congressman, “we continue to have profound political polarization in the country with lots of conspiracy theories, disinformation, propaganda and ideological combat. Those conditions are just unhealthy for everybody and they are especially tough on young people who are dealing with a mental health problem.”

To continue to raise public awareness about these issues – and to honor Tommy’s memory – Raskin is thinking about writing a children’s book that tells his son’s story. For now, though, he wants to take advantage of the fact that cancer treatment has forced him to cancel “a lot of speeches and public appearances” to write “a number of essays and articles” that will draw from the experiences that life – and history – had in store for him.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.