LA Mayor Eric Garcetti on racism scandal: ‘For the city to heal, the council members need to step aside’

While in Buenos Aires for a summit on climate change, the Democrat spoke to EL PAÍS about the racist comments made by three municipal politicians who compared a Black child to a ‘monkey’

Earlier this month, the president of the Los Angeles City Council, Nury Martínez, resigned after she, a labor leader and two fellow Latino council members – all from the Democratic Party – were caught on tape making racist remarks.

The recording revealed an hour-long conversation from October 2021. The main subject of the discussion was how Martínez and councilmen Kevin de León and Gil Cedillo planned to gerrymander municipal districts to favor their allies and increase their political power.

The three municipal politicians also made dozens of racist comments about African Americans and Latin American people of Indigenous descent. At one point, the adopted Black son of a member of the city council was referred to as “changuito” – a monkey – and migrants from Central America and parts of Mexico were called “ugly and dark.” The release of the recording sparked fury in Los Angeles and across the country. Even President Joe Biden weighed in, saying that the three council members should resign. While Martínez did so, De León and Cedillo have not.

Cedillo lost his Los Angeles City Council seat in June of this year, meaning that his tenure will end soon. However, De León – a former state senator and a mover-and-shaker in the California Democratic Party – is hoping to hold on to his seat for another two years. He has refused to resign.

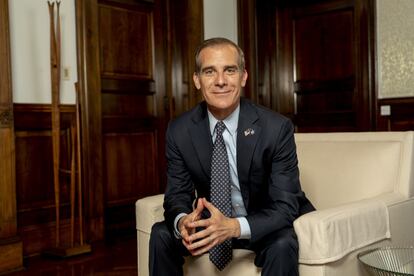

Eric Garcetti, 51, the Democratic mayor of Los Angeles, is in Buenos Aires, Argentina for a summit to discuss how cities can handle climate change and how high-income countries can help developing nations in the green transition. He took some time out of his schedule to speak with EL PAÍS about the racism scandal that has rocked his city, as well as about the subject of climate change.

This interview has been translated and edited for clarity.

Question. How did you feel when you heard the comments that were made by Martínez, De León and Cedillo?

Answer. I felt very sad. They’re old friends… leaders that had the capacity to do important things. Nury Martínez pushed a lot of policies that benefited families. Of course, there are lines that nobody should be allowed to cross.

Q. Councilman Kevin de León has said that he won’t resign because “there is too much work to do.” What’s the political solution to this situation?

A. They [the councilors] offended so many communities. For the city to heal, for different communities to heal, they need to step aside. I say that not only as mayor, but as a friend. I hope that, in the future, there’s a path for them to return to public service… but I don’t think they understand the pain that they have caused in our community.

When I was elected mayor in 2013, only 2% of our energy came from renewable sources. By the end of this decade, 97% of our energy will come from low and zero-carbon sources

Q. Do you think that this pain could affect the unity of Los Angeles, which is such a diverse city?

A. We’re very united in Los Angeles. Our view of the United States is stronger than ever. We have a community in which everyone feels that they belong. The words of those council members don’t reflect this spirit of unity.

Q. You’ve travelled to Argentina to participate in the C40 World Mayors Summit, which brings together 121 cities from around the world to make commitments in the fight against global warming. Are you satisfied with the results?

A. What we see today are municipal governments rapidly moving towards meeting their climate goals, but national governments that are reacting too slowly. We need more action, more investment and more ideas to accelerate our work. I’m leaving this summit with a lot of ideas and a lot of optimism.

Q. What is LA’s environmental story?

A. In the 1970s, when I was a boy, we had a huge problem with smog pollution – sometimes we couldn’t go out into the street to play. Today, since that period of time, we’ve reduced smog levels by 90% – it’s a success story. We’ve also made progress when it comes to green energy generation. When I was elected mayor in 2013, only 2% of our energy came from renewable sources. By the end of this decade, 97% of our energy will come from low and zero-carbon sources.

Q. The summit has announced $77 billion for initiatives to tackle the climate crisis. Is this enough money?

A. It’s not enough for the Southern Hemisphere – and not enough for the rest of the world, either. In my city – which lies in the North – we need more commitment from industry and the financial sector. We also need to remember that we have a lot of power in our hands, in our neighborhoods, in our schools and places of work. There is power in the actions that we take, even on a small scale.

Q. California has committed to banning the sale of new gasoline-only cars by 2035. Is this a feasible objective given the strain on the electrical grid, especially in the summers?

A. It’s not going to be easy. The need for electricity grows every year. But we’re making progress with solar energy and helping clean energy initiatives get loans. I’m confident that we can meet demand.

Q. How has climate change affected the populations with the least resources to mitigate its consequences?

A. It’s not only about climate change. These vulnerable communities are also victims of pollution. And of poor planning: in many of our cities, there are fewer trees and inadequate public transportation systems. To solve these problems – and to create more economic opportunity – we’re betting on green solutions to achieve equity. For example, building electric vehicles needs to start in the poorest communities, where many people often don’t even have a car. It’s about a change that isn’t just for the rich who can afford Teslas.

Q. What can the United States do to help cities in the developing world?

A. We need to focus more on Latin America. The Biden administration is doing this, but we need to bring more resources to South and Central America, not just to Africa and Asia. My message to President Biden is that the destiny of the United States is here, on this soil. Whether it be due to migration, the environment, or the economy. And I hope that we can help Latin American countries become models of change. The resources exist, the knowledge exists – the industries are present. But we need more help from Inter-American institutions.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.