January 6 committee: Trump hid plans for Capitol march

Tuesday’s hearing into the attack looked at the former president’s links to far-right groups and whether he had planned the rally ahead of time

It’s a tough competition, but the meeting on the night of December 18, 2020, in the Oval Office wins the award for the most “unhinged” of the Donald Trump presidency. That was the conclusion following the seventh hearing of the House select committee investigating the siege of the US Capitol on January 6.

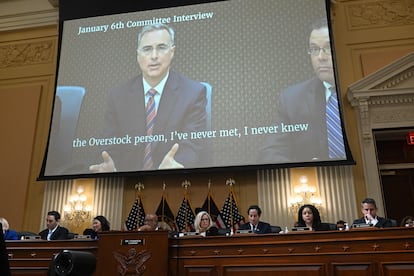

The emergency meeting took place four days after the election, and was attended by several people close to Trump, including one of his campaign lawyers, Sidney Powell, the former mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani and General Michael Flynn, who was then the National Security Advisor. The heated meeting lasted six hours. There was shouting and insults as the group locked horns over the results of the November election. One side believed that the Democrats had stolen the election with the help of countries such as Iran, China and Venezuela. While the other tried to convince Trump that claims of election fraud were “nuts.” This side included then-White House Counsel Pat Cipollone, who after refusing to testify for weeks, agreed to speak with the committee on Friday. His statements, broadcast at Tuesday’s hearing, provide new and important information for the investigation into the January 6 insurrection.

At the December 18 meeting, vividly recreated in a seven-minute montage of taped interviews, Trump came close to ordering the military to seize state voting machines – an idea put forward by Sidney Powell. “To have the federal government seize voting machines, it’s a terrible idea. That is not how we do things in the United States. There’s no legal authority,” Cipollone told the January 6 committee.

The meeting went on past midnight. Once over, Trump expressed his frustration that some of his strongest allies had refused to back his claims that the election was stolen. He calmed his frustration by doing what he knew best: tweeting.

He posted a message that “changed the course of history,” said Jamie Raskin, one of the most high-profile members of the January 6 committee. It read: “Statistically impossible to have lost the 2020 Election. Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild.” That frosty day in winter, Trump held a rally and fired up his supporters, even though he knew that some of them were armed, as revealed by former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson in a hearing last week. The Republican encouraged the protesters to storm the Capitol, and said he even wanted to join them.

The tweet is well known, but at Tuesday’s hearing, it was revealed that Trump had written another message and decided not to send it. An undated draft tweet, marked as being seen by the president, promoted his Jan. 6 speech at the Ellipse and concluded: “March to the Capitol after. Stop the Steal!!”

The finding suggests that Trump had been planning the rally, but wanted to appear as a spontaneous decision – an idea backed by other testimony heard by the January 6 committee. Indeed, the committee found that Trump campaign spokeswoman, Katrina Pierson, wrote in an email after a Jan. 2 call with then-White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows that the president’s “expectations are to have something intimate at the Ellipse and call on everyone to march to the Capitol.”

Two days later, another organizer said it was important to keep the plan a “secret” so as to not alert the National Park Service, which is in charge of granting permits for rallies in the National Mall, a landscaped park near the US Capitol.

Tuesday’s hearing also shed light on the links between Trump and far-right groups such as Oath Keepers and Proud Boys. Members of both groups are facing seditious conspiracy charges for their role in the insurrection. Stephen Ayres, who pleaded guilty last month to charges related to his actions at the siege, told the committee that he regretted allowing himself to be misled by Trump. “I think everybody thought he was going to be coming [to the Capitol]. He said in his speech that he was going to be there with us. I believed it,” he said. “I felt like I had horse blinders on, I was locked in the whole time.” At the end of the session, he apologized to a Capitol police officer, who was one of the 140 officers injured in the attack.

Jason van Tatenhove, who was a member of the Oath Keepers until 2018, also testified, describing the group as “a violent militia.” “The best illustration for what the Oath Keepers are happened January 6, when we saw that stacked military formation going up the stairs of our Capitol.” The committee also shared videos of Trump supporters threatening to kill Democrats. Jamie Raskin, one of the most prominent members of the committee, described the violent rhetoric resulting from Trump’s call as “openly homicidal.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.