Man whose harrowing image defined Bosnian conflict takes denialists to court

A photo of an emaciated Fikret Alic was seen around the world in 1992. He and other former prisoners are taking legal action in the wake of comments made about their plight on Serbian television

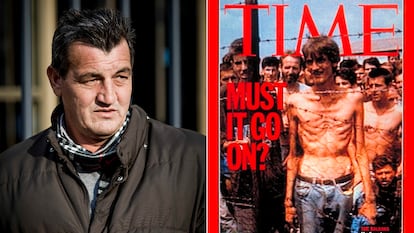

On August 17, 1992, TIME magazine published the image of an emaciated man behind barbed wire on its front cover. It symbolized the return of concentration camps to European soil half a century after the Holocaust, and would come to define the Bosnian war. It was taken by a group of British journalists in Trnopolje, one of the three camps set up by Bosnian Serb forces near the Bosnian town of Prijedor. Everything except Fikret Alic’s smile visually recalls the Nazi genocide.

In February 2021, almost 30 years later, Milomir Maric, the host of a morning program on Serbia’s Happy TV channel, chatted with Predrag Antonijevic, the director of the controversial film Dara of Jasenovac – the country’s candidate for the Academy Awards. Alic was described without being named as “the skinny one” with “tuberculosis.” The camp where he was held was mentioned as a place where one could enter and leave freely, created by Bosnian Serbs “to prevent someone from killing” the people held there. “Then they fed him [Alic], took the skinny guy away and showed him in a circus around Europe. That’s their propaganda,” Maric said.

Their conversation would not be considered out of place in a country that has difficulty coming to terms with its role in the wars of the former Yugoslavia. There is a permanent sense that Serbs are demonized, that the massacres they committed are not contextualized, and that the enemy’s atrocities are ignored. The top Bosnian Serb leader, Milorad Dodik, one of Bosnia’s three rotating presidents, considers the Srebrenica genocide to be “the greatest myth of the 20th century.”

Although this is not an isolated episode, something snapped inside Satko Mujagic, a survivor of the Omarska camp. “I thought, ‘what else could they do now?’ First, for all the evil they did to us, and 25 years later, I have to hear on public television that the place where I was detained was not a camp. It wasn’t like it was anonymous people denying what happened in comments on the internet, it was on state television, watched by hundreds of thousands of people. I felt enough was enough,” Mujagic said from the Netherlands, where he rebuilt his life after arriving as a refugee.

Mujagic, 49, a University of Amsterdam law graduate, contacted a well-known human rights lawyer in Belgrade and phoned Fikret Alic. The two agreed to lodge a complaint to Serbia’s electronic media regulator, REM, together with the 3,200-member Association of Detainees of the Kozarac Camp. In its response last May, REM acknowledged the personal offense to Alic, but dismissed the complaint.

Faced with this rejection, they decided to go a step further and take their case to court. Last July, they filed a lawsuit against the regulator at Belgrade’s administrative court, aiming to force it to reconsider. REM refuses to comment on the case, considering that any statement “could be interpreted as pressure on the court and other participants in the proceedings,” it said in a written response to this newspaper.

Alic now lives in Bosnia after a long stint in Copenhagen, and although he is part of the lawsuit, he sees it with more emotional distance. “It is unfortunate to see that today some people make fun of our suffering and deny it, although personally I don’t pay too much attention to it, because I know what we lived through. This is not a matter of opinion, as our testimonies and the trials in British and Bosnia-Herzegovina courts confirmed. I think it would be good to punish the genocide deniers in order to look ahead to the future. And that requires a clear picture of what happened, and means facing the truth,” he said via a series of messages.

During the Bosnian war (1992-1995), Bosnian Serb forces set up dozens of camps to hold civilians alongside Bosniak and Bosnian Croat fighters. They committed murder and rape, as well as beating and starving the captives, according to court records and testimony. Of his months in Trnopolje, Alic recalled “the harshness of the conditions,” but also “the constant fear.” “We feared what each new day might bring and we didn’t know if we would survive. Along with fear, hunger and disease reigned, and we lived in extremely inhumane conditions,” he explained.

Unbearable conditions

When Alic was in Trnopolje, Mujagic was in a nearby camp, Omarska, where some 700 of around 6,000 people living there died. “Some, and I saw one with my own eyes, simply gave up,” recalled Mujagic, then 20 years old. “We didn’t have enough food, we slept on the floor, many of us were beaten, there was no medicine and no showers. Even going to the toilet was dangerous. In those conditions, many people got sick, there was dysentery... At a certain point, the conditions were already so unbearable that people started dying from them, instead of being murdered directly.”

What happened on August 5, 1992, saved their lives, Mujagic believes. A group of British journalists — among them Ed Vulliamy, who years later would become the first reporter since the Nuremberg trials to testify at a war crimes trial — visited the camps, surprisingly at the invitation of Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic. “In the days before, the killings had become more systematic. They were calling more and more people to leave and taking them away. Later we learned that they were all buried. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was in the next group,” Vulliamy said. During the visit to Omarska, when asked about the conditions, one of the prisoners replied: “I don’t want to tell lies, but I can’t tell the truth.” Later, a cameraman filmed Alic as he walked past Trnopolje. Days after the image was published, the Bosnian Serbs removed the barbed wire around the camps and improved conditions for the inmates.

Mujagic is now 49 years old and works for the European Commission assessing compliance with Schengen zone rules. Despite the legal complaint and another he has filed against President Dodik for discrimination and hate crimes, he says he has distanced himself from activism, which he clung to in order to deal with the pain. “In Omarska we saw and experienced things that a human being is not supposed to see. Life as we knew it ended there. I don’t remember laughing once in four years. In 1993 I tried to commit suicide. I found work fast, which helped me a lot to stay busy; and I started a family, but Omarska was always there. I will never get over it. It’s part of my life, but it doesn’t dominate it anymore.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.