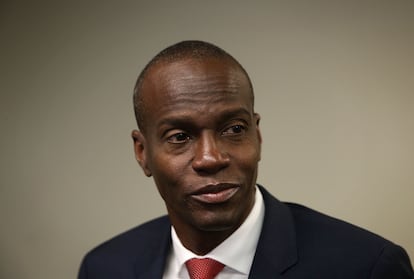

Jovenel Moïse, a president surrounded by too many enemies

The Haitian leader, who was assassinated on Wednesday at his home in Port-au-Prince, had gone up against senators, powerful businesses and Venezuela during his time in office

If Haiti was a movie and the police asked witnesses who could have had a motive to kill the president, the investigating officer would be left with a long list of suspects. The assassination of the 53-year-old president, Jovenel Moïse, has laid bare the social and political decay the country had been mired in since well before the earthquake of 2010 left it in ruins. Moïse’s death at the hands of as-yet unidentified gunmen has exacerbated the chaos and left a power vacuum less than three months before presidential and legislative elections that were providing a road map for the president to relinquish power via the ballot box.

Hugely unpopular and branded an authoritarian, Moïse was clinging to power by a thread. US President Joe Biden held a positive view of holding elections in September in order to stave off a crisis that would destabilize the country and potentially lead to greater migration to the United States.

Moïse was hated by a group of families including the powerful Vorbe dynasty, which controls the country’s electricity supply. In one of the most notable achievements of his time in office, the president had cut them out of the profitable business of bringing electricity to all parts of the country. Moïse also attributed a failed coup to the Vorbes and other influential families who control the economy, and of being behind previous attempts on his life.

Moïse was hated by a group of families including the powerful Vorbe dynasty, which controls the country’s electricity supply

Among his other enemies are the dozens of senators – and the numerous businesses they control in parallel to their legislative duties – who were facing the unemployment lines if a constitutional reform was passed in a vote slated for September that sought to bring an end to the governmental model of an Assembly and a Senate in favor of a unicameral parliament. Even within his own political grouping, the Haitian Tèt Kale Party, Moïse’s naming of a close ally as prime minister created malcontent and fresh enemies in the corridors of power as they saw their own influence placed under threat.

The president also had a significant external foe: Venezuela. If Haitian leaders are clear on one thing, it is that their terms can be expected to last as long as it takes the US to give them the thumbs down. Over the last four years, Moïse had lived in an idyll with Donald Trump in the White House, among other reasons due to his activism against Venezuela and his decision to cut trade links with the Bolivarian states. The Chavist machinery in Caracas responded by leaking documents accusing Moïse of corruption linked to the PetroCaribe alliance, which sparked the instability Haiti has been embroiled in in recent years. It was no coincidence that in its official communiqué following Moïse’s assassination, the Haitian government said that the suspects spoke Spanish.

At the same time, Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier, a former police officer who runs one of Port-au-Prince’s most violent and powerful gangs – and who has been empowered by the booming industry of kidnappings in addition to arms and drug trafficking – appeared on social media recently threatening to seize power and calling for an “insurrection of the impoverished.”

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.