Haiti’s president hits out at ‘coup attempt’ and vows to complete disputed term

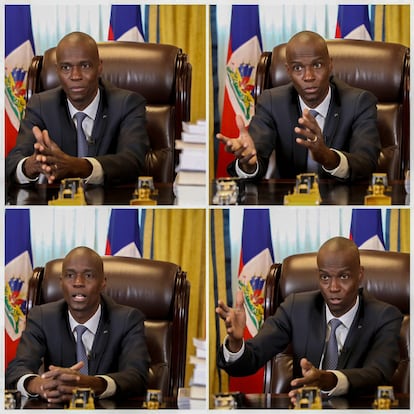

Speaking to EL PAÍS, Jovenel Moïse blames the opposition and powerful figures in the country’s economy for attempting to remove him, vowing to remain in power for another year

Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse has accused the political opposition and wealthy backers of mounting a coup attempt against him, as a dispute over the end date of his current term in office has been accompanied by an upsurge of violence on the streets of the Caribbean country.

In an wide-ranging telephone interview with EL PAÍS, Moïse, 52, hit out at Joseph Mécène, a 72-year-old judge who recently declared himself president, and attacked powerful families who “control the main resources of the country, and who have always installed and removed presidents, using the street to create chaos”.

The corrupt oligarchs who are used to controlling the president, ministers, parliament and judicial system think they can take the presidencyPresident Jovenel Moïse

Moïse was elected in 2015 for a five-year term to start the following February, but that poll was voided due to fraud allegations. He was confirmed as president in a subsequent election a year later, but the opposition argues his time is already up and he should have left office.

“My mandate began on February 7, 2017, and ends on February 7, 2022. I will hand power back to its owners – the Haitian people,” he said, speaking from his office in the capital. “The corrupt oligarchs who are used to controlling the president, ministers, parliament and judicial system think they can take the presidency, but there is only one way of doing this: through elections.” Moïse added that he would not stand again for office in line with the current constitution, which prohibits consecutive terms.

Haiti, the poorest nation in the Americas, has struggled to recover from devastating natural disasters, and is grappling with a tanking economy and armed gangs who have de facto control of sectors of the capital, Port-au-Prince. The arrest this week of 23 people accused of conspiracy and attempted murder of the president has ratcheted up tensions.

Supreme Court Justice Mécène swore himself in a message recorded in a room with no witnesses, apart from a Haitian flag and his Facebook account. The move has so far been ignored by the international community. As he was doing so, a plane from the United States landed with dozens of deported Haitians on board, 21 of them children, underlining the country’s many difficulties.

Regardless of the simmering domestic atmosphere, Moïse so far has the backing of the United States and the Organization of American States (OAS), which are keen to avoid further violence and political gridlock in the country. Analysts have said the US and OAS will apply pressure for elections to be held this year to ensure Moïse has a clear successor, rather than to oust him now.

Moïse enjoyed a good relationship with former US President Donald Trump, owing to the Haitian leader’s repeated denouncement of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Venezuela responded by accusing Moïse’s administration of corrupt handling of money from PetroCaribe, a loan programme designed to help Caribbean countries create their own development funds.

While the Haitian president’s relationship with President Joe Biden is facing its first test, he is optimistic about working with the newly elected leader. “I have not had the opportunity to speak with Biden personally, but relations with the United States are at their best, and I don’t think that will change in future,” Moïse said. There is little he can do to stem an avalanche of criticism over his governance, however. “We are witnessing the making of a Somalia in the Americas,” Ralph P. Chevry, a board member of the Haiti Center for Socio Economic Policy, told The Washington Post this week.

Until now, governments were the puppets of business, but that’s no longer the case and so those who once felt untouchable are really taking it badly

Moïse has ruled by decree since he failed to call legislative elections in 2019, effectively leaving the country without a parliament. This has exacerbated accusations by the opposition that he is acting like a “dictator”, though he insists they are the ones acting undemocratically.

“This coup d’etat is not a single incident but a sequence of actions. Until now, governments were the puppets of business, but that’s no longer the case and so those who once felt untouchable are really taking it badly,” he told EL PAÍS. Moïse has previously blamed families who largely control the country’s electricity supply for sabotaging his rule and stoking violence.

He has also attracted criticism for decreeing the creation of a secret service, and referring to street protests as “terrorism.” Moïse said that being criticised was “normal” and that he “understood the preoccupations” of his accusers, and was “working hard to dispel their fears.” At the same time, he dismissed the idea of widespread protests against his rule. “Mass protests are not taking place all over the country. These are small groups of 30 to 50 people in Port-au-Prince or [northern commune] Gonaïves. Violent people who are being manipulated,” he said.

Another contentious policy that Moïse seems intent on pursuing is reform of the 1987 constitution, which affords the president little power in favour of parliament and a prime minister. Moïse said he would hold a referendum in April on plans to create the post of vice-president, to combine Haiti’s two legislative chambers, and expand the popular vote to the diaspora community. He would not personally benefit from these changes, he noted. “The new constitution will attempt to balance out the power currently concentrated in the legislature,” he said. “If I give you an example, I won the last election but for 22 months I could not keep a single one of my promises because I could not even make appointments to my cabinet.” Moïse wants to allow “the most capable and prosperous Haitians” – referring to the diaspora – to become ministers and lawmakers too.

Politics aside, Haitians are panicked by the growth and strength of violent gangs. Kidnappings and robberies are common in Port-au-Prince, even forcing organizations such as Doctors Without Borders to suspend some of their work there. Anecdotally, there is a sensation that there are more weapons on the streets than ever before.

“In a country where there is a lot of misery, it is normal among people with no conscience to prey on the weakest to do their dirty work, and guarantee their interests,” the president said. “When you see a person with no shoes on holding a gun worth thousands of dollars, you know that they work for criminal groups.” Moïse pointed to the appointment of a new police chief as evidence he is serious about gun violence, but admitted he was fighting “an arms business” that has engulfed the country.

In the midst of its political crisis, Haiti has had little time to commemorate the anniversary of a devastating 2010 earthquake that killed at least 250,000 people. Moïse also has to contend with how little quality of life has improved in the so-called “Republic of NGOs”, which has benefited from billions of dollars of aid. “I am sorry to say it as the president of Haiti, but we missed an opportunity to remake the country. We had the problem of political instability and we didn’t know what to do with the projects that came to us from international funds. However, we cannot change history and we have to start again. It was tough for us that for 11 years we were given a lot, and the results are very minimal”.

Meanwhile, the president has little time left to accomplish all of his own promises. Moïse’s pitch to the electorate of the first Caribbean republic in 2015 was that he would bring electricity to every home, but just 44% have access today, according to the US Department of Energy.

English version by Jennifer O’Mahony.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.