Football, fashion and funk: Laurie Cunningham, the first Englishman to play for Real Madrid

The London-born forward, a trailblazing fashionista and free spirit, wanted to be a dancer but ended up as the most expensive signing in the Spanish club’s history in 1979

Laurie Cunningham is best remembered in Spain for being the first British player to turn out for Real Madrid, but he is also fondly remembered by fans of Rayo Vallecano, in the south of the capital. In the UK, Cunningham is remembered as a trailblazer who was one of the first Black players to represent his country, earning his first international cap a year after Viv Anderson made his pioneering debut for England in 1978, as well as a symbol of the battle for racial equality.

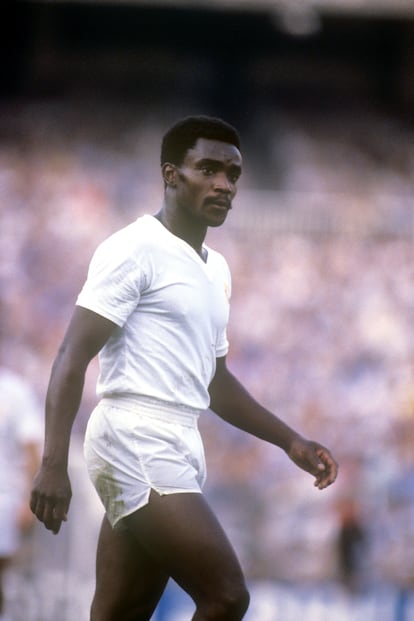

Cunningham’s career was blighted by injury and cut short when he died in a traffic accident in Madrid in 1989 at the age of 33. But the player dubbed “the Black Pearl” in Spain shone on the pitch. A dancing winger who liked to take on defenders, he was also one of the first members of a working-class subculture in the UK that emerged toward the end of the 1970s called the Soulboys due to their tastes in American funk and soul music. He was also a fashionista and free spirit who never quite fit the mold that society tried to place on him.

In a book entitled Different Class: Football, Fashion And Funk. The Story Of Laurie Cunningham, published in 2019 and recently translated into Spanish by publisher Colectivo Bruxista, the player’s life and career are examined by British journalist Dermot Kavanagh. “I remember Cunningham as a player at West Bromwich Albion in the 1970s when I was a kid. Then, apparently, he disappeared when he went to Spain. There was little coverage of Spanish, or even European, soccer in England at the time and he was largely forgotten until his death was reported in 1989. After several years of not thinking about him, my teenage memories came flooding back when I saw a photo of him wearing a Gatsby-style suit. That’s when I felt I had to find out more about him,” recalls Kavanagh. “Then, when I discovered he was a soulboy, I knew there was a much bigger story to tell about Laurie, about London and the vibrant youth culture of the time. London’s Black soulboys have been overlooked in the British pop culture narrative, so it’s not surprising that Cunningham isn’t known as a dancer and style icon. It was an underground scene that relied on word of mouth. The 1970s explosion in youth culture in Britain is dominated in the media by punk, which was all over the music press and television. Soul and funk received very little coverage at the time and were largely ignored. The soul clubs in London were interesting, mixed, and multicultural. Filmmaker Don Letts [a key figure among those who documented the musical effervescence of the era in the UK] told me that no scene has ever been as mixed as that one.”

The soulboy soccer star

Kavanagh’s biography of Cunningham shares more traits with No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, the memoirs of Sex Pistols front man John Lydon, than most books about soccer players. “They are exact contemporaries. They were both born in 1956 in Holloway and grew up in Finsbury Park. Both were self-made, in the sense that no one taught them how to do what they did. Both were the children of working-class immigrant parents and very shy as teenagers, who nevertheless loved clothes and dressing in a distinctive way. And both were shaped by London. I don’t think the punk scene or the soul scene could have happened anywhere else, and they both grew up in homes that also loved music,” notes Kavanagh. “Laurie’s father, Elias, was a big fan of ska and jazz and his son played piano and danced at family gatherings.”

The Cunninghams came from Jamaica, emigrating to the UK in the 1950s as part of the Windrush Generation, encouraged to leave their Commonwealth country homes to move to Britain and fill the worker shortages resulting from World War II. On arrival in the UK, however, they found themselves treated as second-class citizens. Laurie Cunningham stood out on the soccer pitch from a young age, although his idols were Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. When Hong Kong martial arts movies became mainstream, Bruce Lee was added to the list and Cunningham took up karate, all of which shaped his later playing style.

Around 1973, Cunningham became one of the star dancers at the London Soho club Crackers, a gay venue that ended up being frequented in equal measure by straight and homosexual people, Black and white, and which soon became the influential epicenter of jazz-funk. It was frequented by up-and-coming musicians such as Jazzie B of Soul II Soul and house DJ Terry Farley. Dance-offs were part of the attraction of Crackers, and often it was Laurie who would win. “At that time, the Black community could only meet in churches, community halls and illegal bars. We created something, but we were never recognized. The London soul scene, from which many creative minds were born, was created out of sheer survival,” recalls Dez Parkes, a regular opponent in the dance-offs, in the book.

Cunningham was just as groundbreaking when it came to clothes, as those who saw him get off the Leyton Orient team bus one afternoon still recall. Cunningham, who began his career at the London-based side in 1974, was wearing a gangster’s suit, complete with shirt, tie with pin, two-tone shoes, fedora, and cane. “You had to be very brave to dress like that, especially in the soccer world,” notes Kavanagh. Cunningham was a regular at the fashion stores on the King’s Road in Chelsea (including Sex, the Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm MacLaren store where the Sex Pistols were born) and among the second-hand markets in Camden, where he bought clothes from the 1940s and 1950s that he combined with designer items from exclusive brands.

According to Kavanagh, by dressing so differently, he was saying that soccer wasn’t the only thing that mattered, that it didn’t define him, and that clothes could be used as a tool to explore different aspects of his personality. Cunningham also acquired a reputation as an eccentric due to his lack of punctuality in arriving for training. His relationship with a glamorous white girl, Nikki Brown, was also frowned upon by a society that at the time was still not very open to interracial couples.

When Cunningham emerged, alongside other Black players such as Cyril Regis and Brendan Batson at West Brom — leading to the formation of what their coach, Ron Atkinson, famously called the “Three Degrees” — and Clyde Best, Clive Charles and Ade Coker at West Ham, racism was rife in British stadiums. Insults and banana-throwing were commonplace but beyond the occasional Black Power salute to the stands, Cunningham endured the affronts from Orient onward with stoic elegance and a refined footballing technique that made him one of the first Black players to wear the England jersey, in 1979. He was, at the time, one of the most promising and exciting players in the world. So much so that, in an era when international soccer transfers were still few and far between, Real Madrid made him the most expensive signing in the Spanish club’s history.

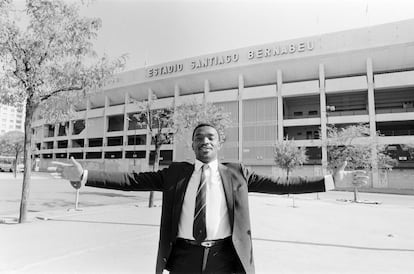

Real Madrid culture shock

When he arrived in the Spanish capital in 1979, Cunningham’s characteristic innocence began to crack. At a Real Madrid team still very much conditioned by the Francoist concepts of discipline and decorum imposed by Santiago Bernabéu, he was received with suspicion, even among his own teammates, who were jealous of his salary. Legend states that in his very first training session, he playfully nutmegged José Antonio Camacho — playing the ball between his legs, a trick designed to make defenders look foolish — immediately arousing antipathy in the dressing room. The veteran Gregorio Benito later sold Cunningham a mansion in the town of Las Matas for a fortune, leading the Englishman to eventually confess to feeling cheated by his teammate.

It was an era of democratic awakening in Spain in the aftermath of the Franco dictatorship but many traits of national Catholic morality remained. The wives of the other players did not understand that Nikki and Cunningham were not married. There was also a youth subculture emerging, the Movida madrileña, throwing off the shackles of Francoism and providing a city nightlife full of temptation. “It must have been difficult to adapt to a new country, and his girlfriend at the time speaks of the isolation and loneliness he often felt,” Kanavagh says. “At first there was a sort of exotic curiosity; people would swerve their cars to get a closer look. The discipline of a club like Real Madrid was also a shock after England. I don’t think he ever adapted to it, it went against his curious and instinctive character. He came to love Spain, he liked the lifestyle and culture, he learned the language and made many friends, but he later felt aggrieved by the way he was treated by Real Madrid toward the end.”

Cunningham didn’t enjoy a huge amount of glory at Real Madrid, despite winning a league and cup double in the 1979-80 season, his first and most productive in Spain. He was given an ovation for his performance in a 2-0 win at Camp Nou, the stadium of Madrid’s arch-rivals Barcelona, but the robust nature of Spanish defenses meant that he was often injured by crunching tackles. One of the worst he received was meted out by Real Betis player Bizcocho, which nearly ended Cunningham’s career. A subsequent photograph of the player with Nikki in the famous nightclub Pachá, dancing clumsily with a cast on his foot, led to a fine of one million pesetas (the equivalent of €6,000) from the club. Real Madrid showed him the door shortly afterward and he began an erratic pilgrimage that took him to Sporting Gijón (a city where he had a daughter he wanted nothing to do with, according to the book), via a loan at Manchester United, Olympique Marseille, Leicester City, Rayo Vallecano, Wimbledon — where he was part of the FA Cup-winning side that beat Liverpool in the 1988 final — Charleroi and, in 1988-89, Rayo again, where he scored the goal that took the working-class suburban side back into the top-flight.

“After the injury problems and bad press he had suffered at Real Madrid, when he arrived at Rayo, Cunningham was a very different person,” says Kavanagh. “He had to learn to deal with disappointment and, at times, had trouble keeping his career from going off the rails. At Rayo he knew he was no longer the quick forward of old, but he adapted and played an important part in their promotion to Primera División. A purely personal theory I have is that Rayo were a similar-sized club to Leyton Orient, where Cunningham started out. Both clubs were in unglamorous, working-class areas of the capital, with a strong community identity and a thriving immigrant population. To Cunningham this might have been familiar and he felt at home at the club.” During his second spell at Rayo in 1986-87, Cunningham married Silvia Sendín-Soria and had a son, Sergio. Despite his role in returning the team to the top division in 1989, he would not have the chance to go up against his former employers, Real Madrid, the following season. In the summer of 1989, his car crashed into a lamppost on a highway leading out of the Spanish capital.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.