Hispanic-American cuisine: Older than the U.S. Constitution

Spain and Latin America have contributed significantly to that blend of flavors that is American multiculturalism

There is a saying in Spanish that goes, “Love enters through the kitchen.” And it should be added that so does identity and the sense of belonging. Each family has its particular flavors and culinary secrets, like my cousin Eddy’s black beans and other flavors treasured for generations. However, that family one day will be an entire country of more than 330 million inhabitants from origins as diverse as any multicultural family nowadays, still enjoying the smells and flavors of that melting pot and sowing the seeds of gustatory memory that future generations will long for. That’s what we call a Homeland: a territory projected into the future, where memory and nostalgia merge.

The culinary legacy of Hispanics in the United States is extensive and even older than the Constitution. It’s common knowledge that Hispanic presence in the United States spans over four centuries and spreads along the southern border and as far north as the current state of New York, where the first non-Native American to live independently was a Dominican man, Juan Rodríguez. Rodríguez arrived in what is today Manhattan in the spring of 1613 as part of the crew of a Dutch merchant ship allegedly carrying out smuggling activities on the Hispaniola coast on its way back to Europe. The Santo Domingo native stayed on the island for at least a couple of years, based on historical documentation.

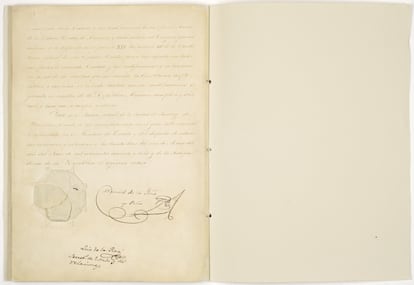

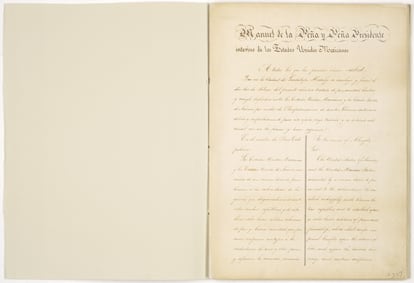

Rodríguez’s story could be an anecdote since “one swallow does not a summer make.” Still, in the southern United States, a massive chunk of the population can trace their ancestry back through the generations to the original setters and livestock ranchers from New Spain (Mexico) and Spain more than 400 years ago, far before the border passed over entire towns with the Guadalupe Hidalgo treaty that officially ended the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) ceding 55% of Mexican territory, including the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Mexico also relinquished all claims to Texas and recognized the Rio Grande as the southern boundary with the United States.

By September 1787, when the Constitution of the United States was signed, climbing aboard the American experiment, “a group of states with different interests, laws, and cultures,” the Hispanic sap was already in its roots and feeding that alliance, even literally. It is believed that the Founding Fathers, meeting in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention, had dinner at City Tavern—a restaurant still running that is dedicated to preserving historical dishes from the 18th century—and it is possible that at least some of them had as an appetizer the popular Philadelphia pepperpot soup, a hearty, spicy, stew-like soup which is a hybrid of Spanish and West Indian traditions made of beef tripe, taro root or potatoes, onion, habanero pepper, spices and greens, mixed in that natural, cultural blender that is the Caribbean, a genuine melting pot of all cultures and races, and a laboratory of transculturation and syncretism. As a trivia fact, pepper pot soup is one of the original flavors of Campbell’s canned soups, sold for 12 cents and available for over 100 years until it was discontinued in 2010.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Hispanic population in the United States has reached 63.7 million, 19.1% of the total population, making it the nation’s most significant racial or ethnic minority and the United States the second country in the world with the largest Hispanic population after Mexico. The U.S. Hispanic population is also a young, vibrant community with a median age of 30.7 years and a purchasing power projected to reach $2.6 trillion by 2025.

“Hispanic Americans contributed $2.8 trillion, or 13%, to U.S. GDP as of 2020. If the Hispanic population in the U.S. were counted as an independent country, its GDP would be the fifth largest in the world and the third-fastest growing,” revealed Jingqiu Ren in Insider Intelligence’s “Hispanic Consumer 2022″ Spotlight report.

With immigration, traditions migrate but so does cuisine. That’s one of the reasons why Latin and Tex-Mex food recently overtook Italian as America’s go-to favorite cuisine, according to a Datassential report. For Jennifer A. Kingston, author of Axios What’s Next, it means that “the dramatic rise in the U.S. Latino population is reshaping the national palate— and sending restaurant operators south of the border (or thereabouts) to freshen up their menus.”

As the Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink highlights, “Modernization of ethnic dishes is a global phenomenon but has occurred especially rapidly in the United States.” Perhaps the regional cuisine that has undergone the most radical transformation is the millenarian Mexican cuisine, which is the basis of a whole cross-cultural culinary phenomenon along the southern border that has been grafted into regional cuisines, creating, among others, the Mexica-American, Tex-Mex, New Southwestern, and the recently developed Alta California cuisine, a creative fusion at the intersection of indigenous, Mexican-American, and American comfort food with a Cali twist, such as the delicious Hatch Chile Spaghetti topped with grilled shrimps you can try at chef Thomas Ortega’s Playa Amor restaurant in LA.

Under the revolutionary impact of Mexican-American cuisine, typical American dishes have emerged, such as Frito pies, Mission Burritos, the Texan Chili con carne, yellow cheese enchiladas, fajitas, chimichangas, taco salad, cheese dip, tasty sopapillas (New Mexican quick bread), and even the world-famous Margaritas, invented by Pancho Morales on the Fourth of July of 1942 at Tommy’s Place on Juarez Avenue, El Paso, where he was a bartender. “A lady came in and said, ‘Let me have a Magnolia,’” Morales told Texas Monthly in 1974. Since Morales didn’t know how to prepare the cocktail and knew roughly some of its ingredients, he mixed them, adding tequila. “I gave it to her, and she says, ‘Oh, this is not a Magnolia, but it is very good.’ And, I said, ‘Oh, oh, I thought you said Margarita.’ You see, daisy, in Spanish, is margarita. I called it the Margarita because I thought of the flower margarita, like the magnolia. She liked it. That’s how it originated,” Morales told the magazine.

One of the most distinctive dishes of Mexican-American cuisine is the hard-shell or crispy taco, the most common type of taco in the U.S., popularized by the chain of fast-food restaurants Taco Bell. The nacho was born in the border town of Piedras Negras, Coahuila, in 1943, at the Victory Club, as a quick fix snack for a party of Army wives stationed at the local U.S. Army Air Force base (Eagle Pass Army Airfield) after the kitchen was closed, but rapidly gained celebrity becoming the American favorite sporting events snack.

Another showcase of the impact that 60 years of exile and immigration can have on reinventing a local cuisine is Miami, with dishes like the Cuban Sandwich, a South Florida staple never known by that name in Cuba. The recipe of the Cuban Sandwich includes slices of Cuban roast pork, sweet ham, Swiss cheese, pickle chips, and yellow mustard, served on buttered pressed Cuban bread—Tampa, Key West, and New Jersey cities have their variation. Another favorite of the South Floridian is the Elena Ruz Sandwich (turkey, strawberry preserves, and cream cheese in a soft medianoche roll), created in Cuba but gone from the national menus after 1959, like many other traditions such as the national soft drink Ironbeer.

Hispanic immigrants have even developed cooking or roasting techniques, such as la Caja China, a roasting box. This method of roasting pork and other meats is believed to have come from Asia and was introduced by Chinese immigrants to Cuba. However, the truth is that whether this roasting method was used in Cuba sometime in the previous century has yet to be discovered.

La Caja China isn’t used in China either. Until someone proves otherwise, it spread throughout the U.S. and the world from Miami, its original city. Its creator says he saw in 1955 or 56 a similar box used by a Chinese family in Havana’s Chinatown. Although it was not until more than 30 years later, in 1986, that he had the idea of creating his own prototype in Miami, its creator revealed to chatchowtv.

Even recent migratory flows, such as from Venezuela, are speedily building a very particular legacy that fuses flavors and customs. There are many theories about the origin of tequeños, those delicious rolls of wheat dough or puff pastry filled with cheese that are more Venezuelan than the “corotos” and “macundales.” (Don’t worry if you don’t understand those words in quotes; they are pure Venezuelan vernacular that not even all Spanish speakers understand.) However, it is believed that the cheese and guava tequeño version could be a contribution made by the thriving Venezuelan community settled in southern Florida.

Many dishes worldwide have been developed at the intersection of several cultures, whose origin is lost in time, buried in centuries-old recipe books and kitchens, and which several nations dispute. But there’s no doubt that Spain and Hispanic America have contributed significantly to that ajiaco of flavors that is American multiculturalism, which is best tasted at dinner time. Even one of Louisiana state’s emblematic dishes, the Natchitoches meat pie (ground beef empanada), is, according to the website of State Symbols USA, a 1700s Native American creation later improved by the Spanish. Legacy and belonging, if they had to be defined, is that familiar smell that comes out of our kitchens, those wild, fresh, spicy flavors, taking us back centuries before the signing of the Constitution.