The lifecycle of a tampon: Used for only a few hours, it takes hundreds of years to disintegrate

The health impacts of one of the most popular menstrual products have not been studied yet. Here, we explore the item’s journey from creation to degradation

When her mother died of ovarian cancer, Mercedes Escoda did not yet know that what comes into contact with the vagina impacts the body up to 80 times more than what is ingested through the mouth. Cancer can be caused by multiple factors; while there are no studies that confirm that the use of menstrual products is one of them, Escoda was disturbed to find out that some of their components “are classified as carcinogenic,” she said. Following this discovery, she founded the chemical-free pad and tampon company Myalma.

An alarm bell went off for Ramón Vendrell when he was working in the pharmaceutical industry: his gynecologist colleagues were telling him about cases of patients with allergies and vaginal discomfort of unknown origins. “Twenty percent of the visits were due to irritations in this area, affecting the [patients’] quality of life,” he said. Then he learned that the menstrual products these women used contained petroleum derivatives and potential allergens. “Is it necessary to put these [substances] into the body?” wondered Vendrell, who later founded the organic feminine hygiene product company Cohitech.

Spanish menstrual activist and politician Maria Perez was the driving force behind a groundbreaking bill to end the labor inequality that comes with menstruation. She explained that she found a “brutal” lack of data about products “that are basic necessities.” For her part, Mexican doctor Sitara Mehmood, a specialist in gender-based medical inequality and the founder of the organization Medicina sin Violencia [Medicine without Violence], decried the same thing: Our knowledge of “the composition of a pad or tampon is very superficial,” she lamented. She has also treated patients who use these products and have vaginal problems, the source of which cannot be determined.

These stories reflect the reality that women are increasingly demanding transparency from the brands that control the feminine hygiene market. But unlike suppositories and drugs, which are also inserted into the body, “the law does not require them to [disclose information],” said Ana Enrich, the founder of Period Spain, an organization that focuses on menstruation and poverty.

Those of us who have periods use between 5,000 and 15,000 menstrual products over the course of our fertile years. Tampons are the second most popular choice. Although they come into direct contact with the vagina, we know very little about them. As a result, according to the nine experts consulted on the matter, women are unaware of what they’re putting into their own bodies and how it affects them.

Producing tampons

There are precedents for tampon use in World War I, when nurses used tissue to absorb bleeding; slightly earlier in Asia, where women used moss; and even earlier in 5th-century Egypt, where it is believed that women used rolled-up papyrus. But the modern tampon was first patented in 1931. Since then, demand for the product has been boosted by its liberatory effects: suddenly, women could swim at the beach or do acrobatics during their periods. For this reason, some experts claim that tampons favored female autonomy and helped women avoid being victimized for menstruating.

Mireia Sabadell, a PhD in Communications and an influencer at @mybestperiod, agreed: demonstrating that a tampon is not noticeable, and that it allows movement with peace of mind, is linked to the idea of “inhabiting public spaces without the fear of being judged,” she explained. But that also implies that menstruating “is deeply shameful.”

Initially, tampons were mass-produced using chemicals. A conventional tampon today consists mainly of cotton and plastic: polymers such as polyester or polyethylene, superabsorbent polyacrylates, perfumes, chemically processed cellulose such as viscose or rayon and cotton; for the most part, these materials are non-organic and treated with herbicides and pesticides.

Leading brands such as Tampax say that their ingredients comply with the standards of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but the reality is that the American regulatory body does not require manufacturers to itemize all the substances used in tampons and test them. In addition, the FDA exempts the companies from disclosing how the tampons have been processed.

For its part, the Saba company asserts that the substances it includes in its menstrual products are not of concern because of the small quantities used. It also points out that current science “has not yet determined that all of those [substances] can have an effect on hormones.” The brand also claims that its products are dermatologically tested but adds that there is still “no official definition for the term” and that each company “establishes its own testing methods.” In the United States, at least nine bills have been proposed to force companies to reveal all chemicals used in their feminine hygiene products, but none have passed.

Kotex, another industry giant, barely mentions the materials it uses or their possible effects. America Futura requested transparency reports from these three companies: Tampax refused on the grounds of confidentiality issues, Kotex declined after learning of this article’s approach, and Saba did not respond.

The substances that these and other conventional manufacturers include in their products have been linked to cancer, hormonal disruptions and vaginal infections, which affect three out of four women at some point in their lives, according to multiple reports, such as the one by Women’s Voices for the Earth.

The vagina is a living environment, and these substances could alter its microbiota and affect the reproductive organs or the immune system, noted Dr. Sitara Mehmood. “For example, superabsorbent polyacrylates can retain fluids that are necessary for the good health of that part of the body,” explained Ramon Vendrell. “Spanish menstrual pad company Ausonia’s ‘dry and safe’ slogan seems dangerous to me. If I had a dry mouth, I wouldn’t be able to talk or swallow,” he said.

Some tampons also include unspecified fragrances, on the assumption that period blood smells bad: “But have you smelled blood? It doesn’t smell. It smells from coming in contact with the product fibers or from [the product] being used for a while,” Mehmood noted. “It’s simply blood that’s shedding endometrial tissue.”

The Scientific News and Information Service (SINC) reported the presence of parabens in menstrual blood. Other research has found additional contaminants such as dioxins, furans and phthalates; the latter gives tampons a soft feel. All of these substances are considered endocrine disruptors that can unbalance hormone receptors and cause chronic fatigue or affect fertility, for example. The metabolic excretory system “is not completely effective,” and these compounds can accumulate in the body, SINC notes. However, companies do not disclose the use of these substances in their menstrual products.

Moreover, many tampons do not have a one-hundred-percent protective perimeter veil to prevent the fibers from sticking to the vagina, according to a test conducted by Vendrell’s company, Cohitech. “It’s easy to check [for that] with adhesive tape or a lighter,” he said. In addition, Vendrell claimed that 99% of patients who switched to chemical-free products improved their vaginal health: “The quality of the products you use now is a determining factor for the health you will have in menopause. And that isn’t explained anywhere.”

Today, there are no official contraindications for using conventional tampons, despite research linking their components to possible harmful effects. However, without conclusive studies, medical professionals cannot provide informed advice about it to those who menstruate. “Medicine continues to be androcentric,” lamented Maria Perez. “And women make up half of the world’s population.”

Mehmood believes that there is a medical debate about human exposure to contaminants that needs to be pursued: commercial tampons are tested on animals, but the effects on human health could be different.

Using tampons

A lack of knowledge about the feminine hygiene industry extends to the daily use of the products. “Some 90% of us have worn a tampon longer than recommended,” said Enrich, of Period Spain. In the most severe cases, that can lead to toxic shock syndrome, a potentially fatal, though rare, infection. In Mexico, there are brands that do not state the product expiration date and include marketing claims on the packaging that “are not verifiable,” according to the Federal Consumer Protection Agency (Procuraduría Federal del Consumidor).

But Enrich also emphasized menstrual poverty and illiteracy. In Spain, two out of 10 women are included in that category. Thus, some “wear tampons for days at a time” because they have no other choice, she said. In Mexico, where inequality is on the rise, the figure is twice as high. While tampons, along with disposable pads, are the most affordable option in the short term, sometimes they are still too expensive.

Over the course of a lifetime, using disposable menstrual products can cost more than $1000 per person, not counting medications, contraceptives, and heating pads for cramps. In the United States, the total cost can be as high as $18,000. Choosing reusable options—such as the menstrual cup, which can last for up to 10 years—would considerably reduce that figure.

According to Anahí Rodríguez, the founder of Menstruación Digna [Dignified Menstruation], the organization that fought to eliminate taxes on menstrual products in Mexico, menstrual poverty is not just a matter of tampons and pads. In public and private spaces, “the bathrooms are [in a] deplorable [state] or there may not be any at all.” In general, the infrastructure is not prepared for menstruation.

This poverty affects all women who lack access to soap, paper, water, drainage systems and/or places to manage their bleeding in a dignified way. Rodriguez pointed out that this problem exacerbates school and work absenteeism, which further widens the gender gap. In addition, many girls and women choose not to participate in daily activities during their periods, leading them to miss out on everything from employment opportunities to recreation.

Menstruation also remains surrounded by stigma, myths and taboos. In places with strong religious and moral beliefs in Latin America, such factors often determine which menstrual product a woman buys. For example, a box of Kotex Super tampons proclaims that using them “does not affect virginity.” Meanwhile, in its instructions for tampon use, Saba refers to the “V Zone” instead of saying the “vagina.” As Mehmood argued, that’s “because of misogyny, the patriarchal gaze.”

Disposing of tampons

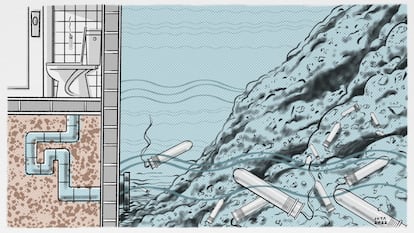

Tampons are created, used and discarded... Those that do not contain plastic can disintegrate in 6 months, but most tampons have a plastic applicator or wrapper and remain on the planet for much longer than their users: it is estimated that they take up to 800 years to decompose.

Assessments of how long it takes for a tampon to disintegrate are made based on laboratory tests, but the actual time may vary according to conditions such as a lack of oxygen or the effects of microorganisms. For example, polyethylene doesn’t degrade easily, likely because single-celled organisms do not eat the material. While using plastic to manufacture tampons has improved the menstrual experience for many women by providing softness and comfort, it has also added to the culture of disposability, thereby condemning future generations to a cycle of non-reusable consumption.

Because they are disposable, tampons cannot be recycled. They end up in landfills and incinerators or in land and aquatic ecosystems (80 percent are flushed down the toilet). For that reason, they are the fifth most common single-use plastic item found on beaches, according to data from the European Parliament. For instance, on an expedition in the United Kingdom, nine tampon applicators were collected per kilometer of sand.

A dearth of studies prevents us from knowing how much menstrual product waste there is on the planet; there isn’t even a universal category for the research. But Harvard University estimates that 20 billion female hygiene products are thrown away each year in the United States alone. Disposable pads are believed to leave a much more harmful environmental footprint than tampons. Manufacturing and waste treatment processes—which involve using fossil fuel energy, carbon emissions and employing large amounts of water—also fail to safeguard the wellbeing of the environment.

Reusable alternatives that are more profitable and sustainable in the long term—the menstrual cup appears to be the best option—have been around for years. But by focusing on disposability, the major feminine hygiene companies have deprived many women of that information.

According to Escoda, it is difficult for organic companies to carve out a niche in the industry: “They don’t let us speak or be found,” she explained. “We’ve had a hard time getting into the supermarkets.” For her part, Mireia Sabadell believes that the industry giants are not interested in promoting environmentally friendly products because reusable items would not generate sales.

To Vendrell, it is essential that schools incorporate menstrual education into their curricula to raise awareness of the impact of using an applicator for three seconds only to have it “take centuries to disintegrate.”

The experts interviewed for this article agreed that eliminating popular unsustainable menstrual products overnight and forcing women to use biodegradable alternatives instead, as Mexico City tried to do in the past, would be a mistake. In the context of high poverty rates and menstrual illiteracy, “everyone should be able to decide which product they want or are able to use,” said Anahí Rodríguez. But she adds that the companies should be the ones to guarantee that female hygiene items are not harmful in any way.

The conventional tampon industry continues to expand amid murky information and lax government oversight. But nowadays, customers around the world are developing a more critical view of menstrual companies’ products: this new perspective is based on the experiences of patients, users and experts who demand the ability to use menstrual products that don’t compromise their own health or that of the planet.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition