Why do we dress?

According to anthropologists, dressing began as a means of fulfilling a psychological function, not just as protection from the weather

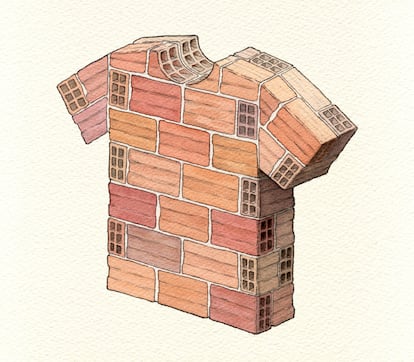

I take notice of the way my patients dress, and the changes that take place throughout the course of the sessions. When a teenager shows up wearing a long-sleeve hoodie in the middle of summer, I wonder why the heat doesn’t affect them… or why it’s so important for them to exacerbate it. What does our way of dressing reveal about us? Does this second skin somehow align with the first? We have a very personal relationship with our clothing; it serves as our exoskeleton. As a way of presenting our self in everyday life, it is a comment on how we blend in or differ from others. Garments can be considered mirrors of the psyche and are – according to the poet Henri Michaux – “a concept of the self that we wear.”

My tendency for “the usual” steers me towards a narrow repertoire: jeans and T-shirts (or sweaters, depending on the season). Patterns that do not require much thinking are useful to me. This, in addition, translates into a sort of constant that allows for the expression of my patients. I distance myself from the fashion trends; they come and go, always carrying an economic connotation. Instead, I subscribe to the principle of Oscar Wilde, who believed that “in fashion” is what one wears, and “out of fashion” what others dictate you should wear. I once heard someone say that one special garment, invested with the capacity to act as a defining feature, is enough to form an outfit — in terms of what it means to us; we are more likely to feel good in it and, most importantly, it improves our self-esteem. More than luxury, moderation and balance constitute the basic element of this other way of understanding elegance. I find it in my denim jacket; it gives me a sense of continuity.

Behind an apparent frivolity, clothing reveals the subtle movements of our desires. As the main element of the adornment we wear, it is a social mask, a non-verbal language, an accurate and valuable indicator of the way we see ourselves and the image we want to project to others in the world. According to clothing anthropologists, dressing began as a means of fulfilling a psychological function before it was adopted for practical purposes. In its literal sense, “protection” means covering the front. Protection is one of the first foundational acts of civilization, as can be seen in the book of Genesis: “They saw that they were naked and they covered themselves.” It is not just protection from the weather; it is, above all, protection from the eyes of others. Thus, protection is basically an ornament.

Designer Issey Miyake has declared that personality is expressed in the space between the garment and the body. In fact, the word “personality” suggests a mask, which in itself is a piece of clothing. To demonstrate this phenomenon, which they named “enclothed cognition,” Northwestern University psychologists Adam D. Galinsky and Adam Hajo assessed the impact of clothing on our cognitive abilities and in our way of thinking. They devised a series of experiments with 50 students who were given identical white coats; some were told they were from a doctor, others, from a painter. When subjected to attention tests that evaluated their ability to identify inconsistencies and differences between two very similar images as quickly as possible, the students who thought they were wearing a doctor’s garment did better. The researchers concluded: “Clothes invade the body and brain, putting the wearer into a different psychological state.”

Our attitude towards clothing is exquisitely ambivalent. In The Psychology of Clothes (1930), psychoanalyst John Carl Flügel stated that we are born in a condition of narcissistic self-love, the consequence of which, he wrote, is a “tendency to admire one’s own body and display it to others.” Trying to understand what motivates the act of dressing, Flügel continues: “[clothes] cover the body and thus subserve the inhibiting tendencies that we call ‘modesty,’ and at the same time afford a new and highly efficient means of gratifying exhibitionism on a new level.” This double function, fundamentally contradictory, according to Flügel, is the most fundamental fact of all the psychology of clothes. It has as much to do with our desire to expose the body as with our sense of modesty.

Lucian Freud, grandson of the founder of psychoanalysis and a master nude painter, once said during an interview: “When I paint clothes I am really painting naked people who are covered in clothes.” Within their fibers, clothes contain the memory of the first care; they project, in their own way, our dreams and hopes, and reflect the construction of our identity. They are, without question, the only material object that is simultaneously intimate and social.

David Dorenbaum is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.