The guardians of the meteorites of the Argentine Chaco

About 4,000 years ago, an intense shower of these objects fell in the north of the country, turning it into a reserve of great astronomical and spiritual value for the Indigenous Moqoit people

In a remote area of northern Argentina, between the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero, the land is dotted with dozens of depressions. The cause is natural, but not exactly from planet Earth. The culprits are meteorites, or as the Indigenous Moqoit (Mocoví) people call them, gifts from the sky.

The Pigüem N’onaxá (Campo del Cielo, or Field of the Sky) Reserve is a provincial park in the town of Gancedo, Chaco. It is a protected area within a larger zone where, more than 4,000 years ago, a giant meteor, believed to have weighed about 800 tons — roughly the weight of five blue whales — fell. Upon entering the atmosphere, it broke apart, causing a meteor shower that dispersed over an area approximately 100 kilometers long and three kilometers wide (62 x 1.86 miles).

Campo del Cielo is one of the largest known impact craters on Earth. It contains some of the world’s largest discovered fragments, such as Chaco, which weighs 37 tons, measures 2.20 meters at its tallest point, and is the second-largest meteorite on the planet. Also located there is Gancedo, the third-largest, weighing 28 tons, as recorded by scientists in 2016. However, the Moqoit people knew about these iron and nickel objects long before that.

Caressing meteorites

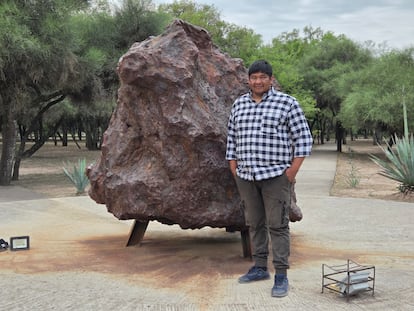

Gabino Mocoví walks slowly among the meteorites. Each time he passes near one, he caresses it with love and respect. “They have a very important meaning,” he says as he strolls on a mild October afternoon in the reserve. “They are gifts from the sky of Lapilalaxachi,” or the grandfather, a group of stars known in academic astronomy as the Pleiades. “Through the meteorites, it connects with us as protection,” he explains.

Mocoví is 30 years old and a Nauecqataxanaq (young Moqoit guide) who, along with 10 other members of the community, welcomes tourists, students, and those curious about meteorites. “We want to convey what Campo del Cielo is from our worldview. Not just from the scientific side,” he says.

For thousands of years, this was a place of pilgrimage and ritual for the Moqoit. Meteorites are part of their identity. They even used them to make tools, such as bolas, a traditional weapon for hunting. Many of the locations of these objects were kept secret for generations.

“The elders believed that meteorites were buried underground and would emerge to be found by the chosen one,” Mocoví adds. In the 1960s, the American scientist William Cassidy led an expedition and found several meteorites weighing thousands of kilograms, such as the Chaco. This massive metal object and its crater are located within the reserve, meters from an interpretation center that houses at least 300 meteorites from the area.

The expedition, and others that followed, brought explanations and new hypotheses about these objects and put Campo del Cielo on the world astronomical map. But, at the same time, the meteorites began to come under serious threat.

Black market

Examples of Campo del Cielo meteorite trafficking abound. On the black market, they fetch thousands of dollars, depending on size and weight. Last July, the U.S. television show Pawn Stars showed a man trying to sell a 20-kilogram meteorite from Campo del Cielo for $7,000. Meteorites are protected by provincial and national laws, but experts say these are insufficient. More enforcement is needed.

It’s a threat that goes beyond science. For the Moqoit, Campo del Cielo is an energetic space. “The elders said that this sacred place has energies that can renew you spiritually. That’s what happens to me and all my companions,” says Mocoví.

As he gazes at the night sky, the guide points to a cluster of stars. “There is Lapilalaxachi, the grandfather who protects the sky and the Earth. He sent the meteorites as protection. And the Moqoit people understand this powerful message. That is why we must care for and respect the meteorites.”

Astronomer and anthropologist Alejandro López explains that the Moqoit people believe that the cosmos, “somewhat like Star Trek, is full of human and non-human societies. The very structure of the universe is determined by the actions and interests of these societies.”

For almost 30 years, he has specialized in ethnoastronomy, primarily that of the Indigenous peoples of Chaco and the processes of change in the history of their astronomical practices. “From the Moqoit point of view, when one relates to the cosmos, one does not only do so with the sky, but also with the forest, with the water... You are not simply interacting with objects, but rather you are essentially reading a map of intentions,” he explains.

Protection for the future

The arrival of scientists at Campo del Cielo, the worldwide awareness of this place, and the smuggling of meteorites opened the door to new conversations among the Moqoit. It was decided that young people were the ones who had to divulge the culture and the secret of the meteorites they had protected for millennia.

“When the training process for the young guides was underway, it was very important to have the authorization and participation of elders from the communities,” explains López, who participated in the training. “A large part of that work consisted of negotiating what things were reasonable to put into words in the context of tourism and visits. And it wasn’t so common to decide that young people would be talking about this topic.”

Mocoví explains that “the elders interpreted this as meaning there had to be a new way of caring for the meteorites. Something had to change. They had to find the courage to speak out and share their perspective. If they spoke, it could be a new way of caring for and protecting the meteorites.” Furthermore, he concludes that “in this way, from now on, the meteorites will be protected by both cultures.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.