The science of dance: At the nightclub, we synchronize like a flock of starlings

A study analyzes the movements that are driven by music compared to those that are driven by partner imitation. Interpersonal synchronization is a mechanism that is deeply present in humans

Many songs have been written about dancing close together, dancing alone, dancing as if no one was watching... The topic has been analyzed from a poetic perspective, but less so from a scientific one. Until now. A new study has analyzed interpersonal synchrony in human dance. At the nightclub, we synchronize like a flock of starlings or a school of fish. Partly because we are listening to the same music, which works as a metronome and sets the tempo; but there is also a social component. Dance moves are contagious, they spread across the dance floor. “It’s something we all know,” explains Giacomo Novembre, neuroscientist and director of The Neuroscience of Perception and Action Laboratory (NPA Lab), who led the study. “But we don’t understand why it happens, how this synchronization process works at an almost subconscious level. That’s what we wanted to find out.”

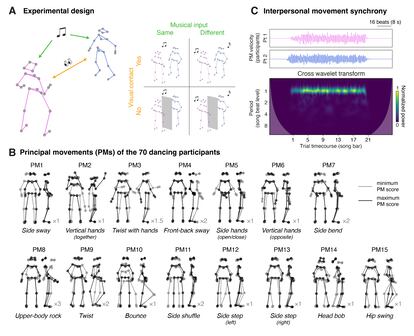

To do so, the team converted one of their laboratories in Rome into a dance floor. The researchers put colored paper on the cold LED lights, to give it a disco atmosphere, invited 70 people and gave them headphones. On the playlist, there were stirring songs by Rihanna, Dua Lipa, Whitney Houston, Gala and Michael Jackson. “Some people danced as if it were Friday night, they were crazy,” explains Felix Thomas Bigand, Novembre’s colleague at the NPA Lab and lead author of the study, with amusement. A camera recorded the dancers’ movements in four possible combinations: 1) when the dancer sees the other participant and is listening to the same music; 2) when the dancer does not see the other participant, but is listening to the same music; 3) when the dancer does see the other participant, but is not listening to the same music, and 4) when the dancer does not see the other participant, nor is listening to the same music.

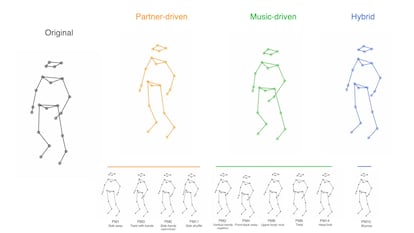

“With this, we got a large database,” explains Bigand. “We used an algorithm to reduce complex dance movements to very simple ones. We saw that only 15 are enough to explain what happens on the dance floor.” It was the skeleton of dance, of rhythm fragmented, chopped up and reduced to its essence. “That’s when we discovered that one cluster of movements synchronized with the music, and another cluster of movements synchronized with the dance partner. And these two processes did not overlap, which was something we did not expect. They are totally independent and do not interact.” Thus, moving sideways or turning your hands are dance steps driven by imitation, while raising your hands or moving your head back and forth (as in a rock concert) are movements driven by the music.

There was only one type of movement that proved to have a hybrid nature, halfway between the social and the musical: the vertical bounce. The dancers started bouncing to the music, but when they saw the other participants doing it, they bounced more energetically and increased the intensity. “It’s like we have a built-in metronome,” says Novembre. “Bouncing makes social interactions very powerful, it is as if you were trying to find a common space.” This did not happen with the rest of the movements, which remained stable in the presence of other dancers. The interesting thing is that this conclusion was reached without a prior premise, without a hypothesis to prove: rather the data explained an intuitive result, of which there are many examples in everyday life.

Bouncing has a tribal component and serves to unite a group. And this is seen in collective dancing, in nightclubs and concerts, as well as in protests and soccer games, where fans jump in unison to cheer on their team. “As a kid, I went to the stadium a lot to see Fiorentina [football club],” remembers Novembre, “and we all synchronized singing and jumping at the same time. I am convinced that this behavior responds to this mechanism. Just like moshing at concerts.”

Sascha Frühholz, professor at the Neuroscience Unit at the University of Zurich, has been studying how emotion is transmitted through sound for years. He praises the new study because it confirms with data what has been suspected theoretically. ”More and more studies point to the notion that interpersonal synchrony is essential for human behavior and important for social interaction in various contexts,” he explains. “And more interestingly, this interpersonal synchrony between humans usually occurs at an implicit level, so that humans are usually not aware that they are synchronizing their behavior.”

This process, which occurs without the need for an external factor, is enhanced when the same music is heard. As musical psychologist Rosana Corbacho said, “When you see the audience dancing in a club to a DJ session, their heart rhythm is synchronized in some way. It is as if our neurons dance to the same rhythm.”

The synchronization of movements is by no means exclusive to humans. We have ritualized it, in dances with specific rules and standardized steps. Even in military marches, but these only enhance something that was already there, in our genetic base: the need to synchronize, to imitate, to coordinate movements to feel part of the group. It’s something that’s also seen in nature. Monkeys are not particularly good at it, but there are studies that analyze how they synchronize when walking. Insects do it especially effectively to organize life in the colony or hive. Fish and birds synchronize hypnotically to frighten or throw off predators.

Damien R. Farine, a researcher at the University of Zurich, has been studying this delicate choreography in flocks of birds for years. “Synchronization means a lot of different things. For example, all birds may respond to a predator’s stimulus and fly off at the same time, but they are not likely to flap their wings at the same time. Flocks of starlings will maintain a large spatial structure, synchronizing their movements, but not the beating of their wings. Some birds that fly in a V synchronize their wings to match the elevations of birds in front, but this is more of a response to the environment and airflow, rather than synchronization per se,” he explains.

The best cases of synchronization in birds, the expert points out, are mating rituals. “In some cases, like in great crested grebes or the clicking of beaks in albatrosses, they are like a dance, but with a fairly specific purpose.” That underlying purpose may also be present in human dancing, the author concedes. “It is likely that this initially led to the ritualization of dance.” From the debutante balls to today’s nightclubs; from the coquettish play of Mozart’s operas to the twerking of Latino music: Dance has always been related to seduction and courtship. The study Music, Dance and the Art of Seduction delves into the anthropological and cultural side of dance, but starts from a biological base, which is what is analyzed in Novembre’s study.

“Interpersonal synchrony is a transversal concept,” says Novembre. “In all societies studied so far, music and dance are used to connect, in many animal species it is used. It is universal.” His study has demonstrated this with data, but deep down it is something that everyone suspects. And it’s something easily observable in a nightclub or a concert. You might, in this context, think that a certain flamboyant dance move was born of its own accord, but if you look around you may well see that someone else is doing it. And it will be difficult to ascertain who did it first, because this imitation works on a deep, subconscious level. It is engraved in our genes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.