Will we ever be able to have a conversation with animals?

The arrival of AI has turned expectations on their head when it comes to achieving complex communication with other species, and makes it possible to analyze their sounds, movements and behaviors to a degree of precision previously unthinkable

Last December, the Whale SETI scientific team had a 20-minute conversation with a humpback whale. The experiment, which took place on the Alaskan coast, entailed reproducing sounds made by a whale attempting to make contact, through an underwater loudspeaker. The University of California Davis’ Dr. Brenda McCowan, lead author of the study, stated that this was the “first communicative exchange between humans and humpback whales in humpback ‘language.’” Or as Finding Nemo’s Dory would put it, it is the first time that humans have managed to “speak whale.”

The arrival of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have set expectations on their head when it comes to achieving complex communication with other species. These technologies allow experts to analyze animals’ sounds, movements and behaviors with a speed and precision that would be impossible for unassisted humans. In the Whale SETI team’s study, for example, this technology was essential to be able to decode and reproduce the whales’ calls. They used advanced equipment to listen and analyze recordings of the animals’ sounds, which helped scientists to detect patterns and variations in their communication, as well as variations in the tone of their calls and in the way they produce sounds.

Kate Armstrong, director of the Interspecies Internet program, is convinced that in the future, we will be able to decode and understand the language of various animal species with a high level of precision. “In a certain sense, we’re already doing it,” she explains on a videocall, pointing out that one of the great challenges in the compilation of data for communication with other species is the presence of noise. “That’s why most of the studies that have been reported on by the media have been done on species who live underwater, where it is easier to extract data,” she says. “This technological advancement brings with it the need to think carefully about how we use these tools and consider implementing regulations to ensure ethical and responsible use.”

The world’s limits

Speaking with an animal using their own language has certain limitations. For example, the recent interaction with the humpback whale was not a conversation in the human sense. That is to say, there was no exchange of ideas or complex meaning. Instead, it was an exchange of sounds that showed that whales can respond in an intelligent and adaptive manner to auditory signals. Researchers interpreted this as proof that whales can participate in a kind of “dialogue” using their own system of audio communication. “Although we can decode their sounds or gestures, differences in cognition and behavior between humans and other species can limit the depth and kind of communication possible,” says Armstrong.

Linguist Mamen Hornos questions “if it is really possible to translate thought between species.” Hornos argues that, even if we share some experiences of reality with other animals, like cause-effect relationships and spatial orientation, we don’t know if they can understand profound human ideas. “And there could also be important things for animals that we don’t understand.”

Hornos mentions philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous aphorism: “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.” This idea suggests that our way of seeing and understanding the world is closely connected to our language. When it comes to human-animal communication, each species may be limited by its own linguistic and conceptual perception of the world. Interspecies communication might never be completely symmetrical or complete, since each species perceives and understands the world through its own linguistic and cognitive “lens.”

The limits of language

Before anyone believed that it was possible to decode the language of whales, there were scientists who conducted famous experiments in an attempt at teaching human language to animals. For example, in 1966, only three years after the novel Planet of the Apes came out, two researchers named Allen and Beatrix Gardner adopted a chimpanzee named Washoe in order to investigate the linguistic capabilities of primates. They treated her as if she were a human child and taught her how to communicate using American Sign Language, a method of communication used by Deaf people. Washoe learned more than 350 signs and could use them to form simple phrases and express ideas of some complexity.

In another case in 1977, a researcher named Irene Pepperberg worked with a parrot named Alex. She taught him more than 100 words and Alex learned to recognize shapes, materials and numbers. He even invented a new way to say “apple,” because the original word was hard for him to pronounce with his beak, which is designed for cracking nuts and seeds. Dr. Pepperberg later recalled that he last words Alex said to her before he died in his cage were, “You be good. I love you. See you tomorrow.”

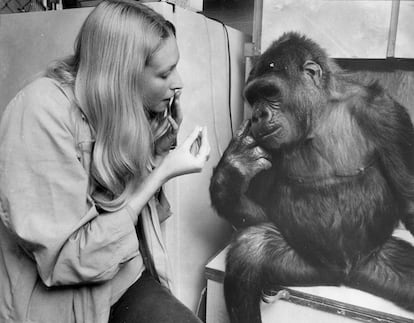

J.M. Mulet, scientific researcher and author, says that, even though there have been “very optimistic” studies at certain points that announced that their researchers had achieved complex communication with animals, these ultimately did not convince language experts. He cites the case of the gorilla Koko, who was trained by psychologist Francine Patterson. It was said that Koko had learned more than 1,000 words in sign language and could carry on conversations. But Mulet doubts that Koko really understood that she was using a new language.

In a passage in which he examines similar work done with other primates, Mulet writes, “It would not be normal, if a chimpanzee was aware of knowing a new communication system, for it not to try to teach it to other chimpanzees, or ask any questions.” In fact, there’s no proof that any non-human animal has asked a question in the sense that humans understand and use questions. Asking questions does not just entail the use of a symbolic language: it also requires self-awareness and the understanding of concepts that are more complex than the communication of basic needs. “The chimpanzee only uses this language when their human instructor directs it at him. For him, it is not communication, but rather, a game,” says the expert.

For Hornos, what keeps an animal of superior intelligence, like some primates, from being able to use human language in the same way that we do, is that they don’t have a hierarchical understanding of language, but rather a linear one. To understand this, think of the phrase “the cat eats fish.” In linear processing, we would understand this sentence by simply reading it word by word, in order: “The,” “cat,” “eats,” “fish.” Each word is understood individually, one after the other. Now, in hierarchical processing, we analyze how the terms are grouped and related. “The cat” is the subject and “eats fish” is the predicate. In this view, we see not only individual words, but also how they relate to each other: the subject “the cat” performs the action of “eating” the object “fish.” Thus, while linear processing sees words one after another, hierarchical processing sees more complex relationships and structures between groups of words.

“There is a hierarchical structure in human language that animals do not have,” explains Hornos. “Animals understand signs and symbols, but they do not have the capacity to understand the syntactic structure and more complex implications of language.”

However, some scientists argue that, given that humans evolved from ancestors that they have in common with other species, there should be a certain continuity or evolutionary relationship between our communication systems and those of other species. Hornos says that the evolution of language doesn’t have to be a linear or progressive process. “Evolution is not always gradual. Similar to life itself, which has significant moments that change us, when it comes to evolution, important leaps also take place,” she says.

Will our relationship with animals change?

Armstrong holds that one of the most significant goals of the Interspecies Internet project is that a better comprehension of the language of animals will increase our empathy towards them. “Understanding the language of endangered species can give us valuable information when it comes to their conservation. For example, knowing what animals communicate about their threats or mating needs can help conservationists make better informed decisions when it comes to protecting habitats and species.” According to the expert, as we better understand how animals communicate, we may come to recognize and value their intelligence and cognitive abilities more highly, and change the way we view and treat them legally and socially.

According to Marta Amat Grau, a PhD in veterinary medicine who is head of the ethology service at the Autonomous University of Barcelona’s faculty of veterinary medicine, progress in the understanding of animal language and communication is positively influencing our relationship with pets. Grau explains that “many behavioral problems stem from a lack of understanding of how we communicate with dogs and cats.”

“Today, we have ample knowledge to interpret, for example, a cat’s meows or a dog’s barks, especially when we analyze them in conjuncture with their body language, which can indicate whether they are experiencing anxiety or seeking attention,” she explains. She also mentions that in recent years, apps have appeared that are designed to translate the sounds or behaviors of pets into a language more understandable to humans. However, she warns that most of these apps have no scientific backing.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.