Why does non-alcoholic beer taste different?

Neither what is advertised as such is always alcohol-free, nor does it retain the characteristics of its alcoholic versions: here is everything you need to know about the processes by which ‘alcohol-free’ beer is produced

“It’s not the same.” That’s the standard response when nutritionists suggest switching to 0.0 beer to reduce your consumption of alcohol. And you’re right: non-alcoholic beer does not have the same taste as normal beer. They are much healthier, but why can’t non-alcoholic beer be just like the alcoholic version? Is it true that everything that tastes good is unhealthy?

Non-alcoholic beer with alcohol

As hot as it may be, it’s best to stop ordering non-alcoholic beer to stay hydrated, as if it were a better version of tap water. FDA regulations allow non-alcoholic beer to have up to 0.5% alcohol. So, you could still be introducing alcohol into your body, and depending on your rhythm, it could be a significant quantity.

How is non-alcoholic beer made?

There are several methods to reduce or eliminate alcohol in a beer. They fall into two categories: preventing alcohol from forming and eliminating alcohol once it has already formed. In both cases, flavor takes a toll. The former system is the most common. It consists of modifying the production conditions so that little alcohol is produced during fermentation. That can be done by modifying the maceration, stopping fermentation or using a special yeast.

The changes in maceration cause there to be less sugar available for the yeast, and, therefore, less fermentation and less alcohol. The grains used to make beer are composed mainly of starch, a complex carbohydrate formed by glucose molecules. If the starch is “cut,” it is reduced to strings of fewer glucose molecules, called simple sugars.

The importance of malt

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or brewer’s yeast, cannot ferment starch, but it can ferment sugar. The first step is to break the long chains of march. That begins with malting, which consists of wetting the grains so that they germinate. The grain releases enzymes and then is dried to stop the germination.

The resulting grain is called malt. It is ground to begin the maceration process. Hot water is then added to activate the enzymes that break up the starch and free the sugars that the last will turn into alcohol. The quantity and kind of sugars released will depend on the enzymes activated, which is controlled by temperature. A low-sugar brew will have a lower quantity of alcohol.

Stopping fermentation to reduce alcohol

Fermentation can be stopped in several ways, including quickly reducing the temperature to freezing so that the yeast stop their activity. Another way is to pasteurize the broth to destroy the microorganisms. Or the yeast can be removed from the liquid.

Using yeast that produces less alcohol solves the problem. A strain that is unable to ferment malt can be used. Except for the type of microorganism used, the process of creating a non-alcoholic beer is the same as that of a normal beer.

What if the damage is already done?

Alcohol can be removed from beer in several different ways. The beer can be heated to evaporate the alcohol. The problem is that if high temperatures are used, reaching a boiling point, a large part of the compounds that give the beer its aroma will also be removed, and the resulting liquid does not even resemble beer. Generally, vacuum distillation is used at a temperature between 30 and 60 °C. That system allows for the complete elimination of alcohol. Unfortunately, though, volatile substances that are part of the beer’s aroma are also lost.

Goodbye, flavor

The alcohol is reduced, but the beer’s taste and smell can be altered. Why doesn’t it taste the same?

None of these processes result in a drink that tastes like the original beer. If the fermentation is stopped, the yeast cannot act on the aldehydes that give beer its aroma, leaving an undesirable taste in the end result.

While stopping fermentation reduces alcohol, it also reduces the presence of important compounds like esters and higher alcohols — those that, unlike ethanol, have more than two carbon atoms, like propanol, isobutane, amyl alcohol and isoamyl alcohol — that give beer its fruity flavor. You end up with an alcohol-free beer with little aroma and a sweet taste.

The heating process does not leave those flavors, but the result could also be improved. Both techniques result in the loss of esters and higher alcohol. When heat is applied, an undesirable caramelized aroma appears.

A light at the end of the tunnel

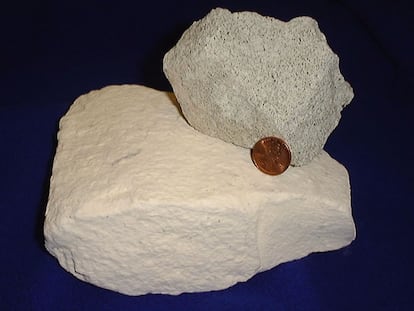

What is food technology for, if not to solve humanity’s most serious problems? An innovative system has been proposed to improve the taste of non-alcoholic beer: using zeolites, porous minerals that function as screens. They act as sieves, and their tiny pores trap aldehydes.

To compensate for the loss of aroma in the heating process, the brewing process can be altered to favor the development of certain compounds, creating a more aromatic brew that helps to balance out the losses. The final beer can also be mixed with a small amount of untreated beer, using an especially aromatic beer obtained by high temperature fermentation or with aromatic extracts.

A recent study proposes using yeast to synthesize monoterpenoids, the compounds that give hops its characteristic flavor, and adding them at the end of the brewing process. For the researchers, it has the added advantage that hops are no longer necessary. In summary, you’re not alone. Many people are working to make the utopia of non-alcoholic beer that tastes like normal beer a reality.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.