From police officer to bloodthirsty kidnapper: Terror in Mexico during the years of ‘The Ear Chopper’

Daniel Arizmendi, who is believed to have kidnapped 200 people, used the modus operandi of cutting off a piece of his victims’ ears, in order to demand ransom from their families. Last week, a judge acquitted Arizmendi in one of the cases against him

“Excuse me, can I see your ears?” The famous Mexican journalist Javier Alatorre asked this of Daniel Arizmendi, during a 1998 television interview. Arizmendi lifted his disheveled, uneven hair to reveal them to the camera. He turned first to the right, then to the left.

“Wouldn’t you be afraid if someone were to cut off your ears with a pair of poultry shears?” Alatorre inquired, continuing his line of questioning.

“Hmm…” Arizmendi thought for a few seconds, his face cold. “Knowing what I’ve done, if it were out of revenge, no, sir,” he replied, without flinching.

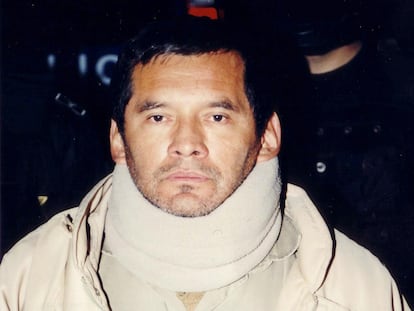

The arrest took place in the early morning of August 17, 1998. Daniel Arizmendi — alias “El Mochaorejas,” translated from Spanish as “The Ear Chopper” — and some members of his gang were taken into custody. This closed one of the most macabre chapters in the history of crime in Mexico during the 1990s.

The bloodthirsty and ruthless kidnapper was believed to have been responsible for at least 200 abductions. His modus operandi was to sever the ears and fingers of his victims.

Shortly after his arrest, upon being questioned by the press, he showed no remorse. “Yesterday was just bad luck for me. I was arrested. That’s all,” he stated indifferently.

Now, 27 years later, Arizmendi has returned to the headlines. On December 24, a judge acquitted the 67-year-old in one of his cases, for the crime of “unlawful deprivation of liberty.” The judge from the State of Mexico (Edomex), Raquel Ivette Duarte Cedillo, issued an acquittal against “The Ear Chopper” in the case of unlawful deprivation of liberty in the form of kidnapping. In her opinion, the evidence presented at the time by the Federal Attorney General’s Office (FGR) was insufficient.

Despite the decision, the convicted man won’t be released from prison. This is because he’s serving a sentence for other offenses related to organized crime, with a penalty of eight years.

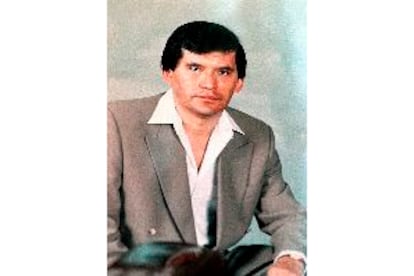

Arizmendi, a native of Miacatlán, a city in the state of Morelos, was 40 years old in 1998. He gave his first two interviews that same year, on the night of August 18. In these recorded segments, he said that, although he was accused of hundreds of kidnappings, he only committed 21. He also confessed to six murders and asserted that he felt no compassion for the people he tortured, nor guilt for his crimes. “Many people think it was for money, but it was just to see if I could do [the kidnappings]. It was a challenge — for the police, for me — to see if the operation would work, if [the families] would give me money.”

“I never got any pleasure from having a large amount of money. I never felt shame, pleasure, or horror at mutilating people,” he confessed to Alatorre.

Rising in the world of crime

In his adolescence, his family moved from Morelos to Edomex, the state that surrounds Mexico City. At a very young age, he started out in his family’s workshop in Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl, where they made hats, baby coats, and scarves. Until he was 20, he moved from factory to factory. He then got a job with the Mexican Navy, and he also worked as a private and public transportation driver. But he didn’t stay in either position for long. At 26, on the recommendation of his brother, Aurelio Arizmendi (who would later become one of his accomplices), he managed to join the Federal Judicial Police in Morelos. He was a cop for only two months… and it was with the police force that he met “El Móvil,” who taught him how to steal vehicles. That’s how he took his first steps into the world of crime.

On a podcast called Penitencia (“Penance”), Jesús Luna Cesma — who was his right-hand man, first in the car theft business and later in kidnappings — said that Arizmendi “changed his line of work,” after becoming quite well-known for selling stolen cars. Luna explains that the police already knew he was a repeat offender, but they didn’t arrest him because they always “got their cut.”

According to Luna, it was because of this impunity that Arizmendi entered the world of kidnappings. His signature — which earned him the nickname “The Ear Chopper” — was to sever his victims’ ears with “poultry shears” or “shoemaker’s shears” (another type of cutting tool), without offering them medical attention. Instead, he would cauterize the wounds with hot shoe polish and avocado ointment. “They said it was the ear, but in reality, what we sent were three or four centimeters of cartilage,” Luna recounts.

The kidnapping of a businessman from Edomex, Leonardo Pineda, was one of Arizmendi’s first jobs. However, according to his former collaborator, it didn’t go well: “It was a failure. When [Arizmendi] got upset, he lost it.”

In a statement, another of his associates recalls that they demanded five million pesos for Pineda, but the ransom was negotiated down to 1.2 million. After two months, his family still hadn’t paid the ransom. Arizmendi sent Pineda’s wife a piece of the man’s ear. According to the same associate, he told her: “Near your house, at the gas station, look in the garden for a plastic bag with a note from your husband.” The woman paid the ransom… but Arizmendi didn’t get the money, because the person he sent to collect it was arrested.

“Daniel gave one of his associates a 9mm Browning pistol. He shot Leonardo Pineda in the head. He left him to bleed to death in the bathroom; then, we tied up his hands, feet and blinfolded him. We wrapped him in a blanket, put him in a pickup truck and dumped him on a road in Chalco. Daniel called Pineda’s wife and told her where to look for her husband,” the testimony details.

In a 1996 interview with the newspaper Reforma — two years before his arrest — Arizmendi was asked why he had cut off pieces of his victims’ ears. He replied: “Because their families, despite having so much money, didn’t want to give [any of] it to me. It was like I told them: ‘God is going to punish you for being greedy [...] For hoarding your money, for not wanting to give it up for a family member.”

“I told them: ‘God is going to punish both of us. What’s more, in the end, who knows who God will judge?’”

According to Luna, he estimates that, during the two to three years that Arizmendi dedicated himself to kidnapping, extortion, and murdering victims whose ransoms weren’t paid, he generated between 100 and 150 million pesos, or approximately $20 million. However, at the time, experts and media outlets speculated that his fortune from his crimes reached even higher levels.

Extreme cruelty toward his victims

The impunity he enjoyed — thanks to police protection — and the extreme cruelty he displayed toward his victims made Arizmendi the emblem of systemic corruption and the defenselessness of Mexico’s citizenry. Two weeks before his capture, on August 5, 1998, the Ear Chopper kidnapped businessman Raúl Nieto Del Río, in the state of Querétaro. According to the case file, a van blocked the path of the victim’s sports car: Arizmendi then rammed it from behind with a utility vehicle. During the struggle, one of his accomplices shot the businessman, killing him.

They took the victim’s body to a hideout, where he was buried in a hole. It had been dug in one of the rooms to hide loot… right under the bed of the man considered to be the Mexican king of kidnapping.

Before burying Nieto, Arizmendi cut off his ears, which he sent to the man’s wealthy family, the owners of a gas company. The parents demanded proof that their son was alive. Arizmendi exhumed, washed and made up the corpse; he blindfolded Del Río’s body and photographed it with a Polaroid camera. According to police sources, he even injected it with saline solution through a catheter, in order to give the deceased the appearance of life.

The Mexican journalist and writer Humberto Padgett went so far as to claim that Arizmendi led a gang which had a protection network that included a state prosecutor, a commander of the Judicial Police and another officer from an anti-kidnapping unit. His story served as the basis for Tony Scott’s film Man on Fire (2004), starring Denzel Washington and set in Mexico City. “The kidnappers were named Daniel — like “El Mochaorejas” — and Aurelio, like his accomplice.”

“I think I would do it all again. Even if I had $100 million, I would do it again. Kidnapping was like a drug for me, like an addiction. It was the thrill of knowing you were taking a risk, that they could kill you. It was like predicting [the future]: ‘Now I’ll cut off this guy’s ear and [the family] will pay.’ And they paid!” Arizmendi exclaimed, as noted by the writer Carlos Monsiváis in his article titled A Bad Day in the Life of Daniel Arizmendi, published in Proceso in 1998.

“I didn’t feel anything good or bad when I mutilated a victim,” the kidnapper shrugged. “It was like cutting bread, like cutting pants.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.