A month of terror without respite in Catatumbo: ‘My daughters are dying, I am going crazy’

A family was caught in the crossfire between two armed groups fighting over the area. They had returned a week earlier, after a month displaced, and left again with grief in their souls and no hope for the future

Doña Blanca Parada (Tibú, 49 years old) clings to the white coffin as if she could still hug the body of her youngest daughter. She is surrounded by a dozen relatives. They all arrived as displaced persons in Cúcuta, a border city in the northeast of Colombia, living from shelter to shelter, with their lives in a backpack and a couple of bags. Her daughter Johanna Quiñones, 18, is one of the 64 fatal victims of the renewed war in the surrounding rural region, known as Catatumbo. She was wounded on Friday, February 14, by two bullets from the crossfire between ELN guerrillas and members of the dissident FARC group known as Front 33, who after a week of truce were involved in a firefight on a road that leads from the municipality of Tibú to El Tarra. The Quiñones’ house, in the Villa del Río area, was caught in the middle of the nearly three-hour battle, between their home and a nursery school.

They had been back in the house, with wooden walls and ceilings, for barely a week. Before that, they had been displaced for a month: men from the National Liberation Army (ELN) ordered them to vacate the entire village in the early hours of January 16. When the shooting started, around 9 a.m., Doña Blanca was preparing breakfast for her children and grandchildren. Johanna was in one of the rooms with her three young nephews, aged two, three and five. Alejandra, her 25-year-old sister, was with her. They threw themselves to the floor, crawled, looked for the youngest ones and protected them, wrapping them in a fetal position. They managed to protect them, but not themselves. Both were hit by the bullets.

Johanna was hit in the head by two shots that went through the wooden planks of the kitchen. Almost instantly, Alejandra felt a flash of pain between her leg and her hip. Both screamed for help, with the children on their chests, but the bullets did not stop. Doña Blanca crawled on the ground to try to help them and stem the blood that was already forming a puddle under their bodies. When the shots stopped, almost three hours later, and a Colombian army tank appeared on the sidewalk, the combatants had fled into the woods.

Blanca threw herself onto the road, in the path of the armored vehicle, without fear of being run over. She needed her pleas to be heard. “The soldiers shouted at me asking if I was crazy, asking how I dared cross the road like that. ‘Yes, I am crazy,’ I told them. ‘My daughters are dying and I am going crazy,’” she recalls, sitting on a plastic chair in the abandoned park of the La Mechita shelter for displaced people in Tibú. It has only been five hours since her life changed forever.

La Mechita is the largest shelter for displaced people in Tibú, created by the Mayor’s Office to deal with a humanitarian crisis that has seen at least 50,000 people forcibly evacuated from their homes. It is private property, with an open hall in the middle and space to house about 250 people, but up to 100 more have been crammed into it. To maintain a minimum of cohesion and community life, those who take refuge there are divided into villages.

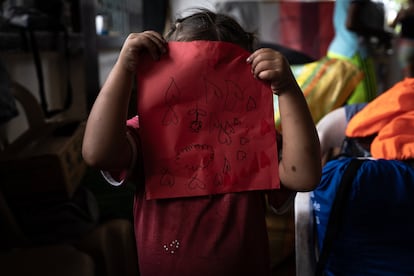

Doña Blanca keeps her gaze fixed on the ground and, from time to time, whispers prayers for her daughters. Johanna and Alejandra have been transferred by ambulance to Cúcuta, about three hours away. “They didn’t want to take them by helicopter,” she says with resignation. They were taken by road, more than 126 hazardous kilometers with bullets lodged in their bodies. After the confrontation, Blanca and her family were again displaced. They shouldered the suitcases with which they had returned and went back to the same shelter they had left with hope, because the conflict had subsided. It was her, her children María and José Miguel, her brothers-in-law Junior and Javier, and her four small grandchildren. They barely have a mattress for the nine of them and the pain and uncertainty for Johanna and Alejandra.

The day is ending and Blanca grabs her cellphone, waiting for a call. She is waiting for news from the Erasmo Meoz hospital. It is 7 p.m. on a Friday night, which in other places or at other times is synonymous with rest, partying, family gatherings. She paces around the shelter in circles. She refuses to eat anything. When Michelle, five, is asked about her mother, she answers bluntly: “They killed her.” Alejandra is in an intensive care unit in the state capital, but the last time the children saw her she was lying on the floor. “It was them,” says the little girl when she sees the military police guarding the shelter with rifles. “Since the guerrillas were also in uniform, she thinks they are the same people,” explains her grandmother. Michelle gets up and goes to play.

***

It has been a month since the war set Catatumbo ablaze. There is no way out or truce in sight. The violence, which had been latent or barely perceptible for so long, erupted on January 16, when the country’s last armed guerrilla group attacked dissident groups of the decommisioned FARC, as well as some signatories of the 2016 peace agreement, which at the time generated so much hope in the country and among residents of Catatumbo. Since then, the dead have numbered in the dozens. As of February 18, the Ministry of Defense had reported 63 deaths: 33 in Tibú, 21 in Teorama, six in El Tarra, one in San Calixto, another in Hacarí and one more in Ocaña. The situation has been described, almost unanimously, as the worst humanitarian crisis in recent decades in Colombia.

The Colombian Air Force has been tasked with delivering tons of humanitarian aid to the area, while the army has sought almost since the beginning of the upsurge in violence to regain control of the region to guarantee the return of citizens. Army commander-in-chief General Luis Emilio Cardozo said on January 24 that he hoped to have control of the most critical points “in one or two weeks.” Outgoing Defense Minister Iván Velásquez said at the time that no return would be allowed until security conditions could be guaranteed. A month later, that has still not happened.

President Gustavo Petro described the ELN’s actions as war crimes and ordered the suspension of the peace talks with the guerrillas, which had already been frozen since May 2024. The situation also led him to declare an emergency and issue decrees aimed at protecting the population. It is also one of the most serious blows to his “total peace” plan, with which he hoped to reach an agreement that would demobilize the guerrillas during his term, but which now seems impossible.

Jesús Gabriel Sánchez, parish priest in Tibú and delegate of the peace commission of the Catholic Church, speaks from his office, which has a privileged view of one side of the central park. “They killed a man there yesterday at this very hour,” he says, pointing with his finger. And he admits, without hesitation, that no armed group has a true desire for peace. “As a Church, we know this. It is a fact. They are not interested in handing over their weapons or returning to civilian life because this illegal world is a business and it has been their way of life.” Nevertheless, he adds, he hasn’t stopped supporting the peace processes: “They are worth it because at least they help to lessen or diminish the intensity of the conflict.” He ends the interview and heads to a village, where he will try to mediate with a guerrilla to achieve the release of a kidnapped person. Afterwards, he will hold a mass.

Tibú, the most populated municipality in Catatumbo, has been militarized since January 24, when, after a bloody week, the army managed to deploy in the area. Even so, in broad daylight, homicides continue to be committed in the park, the main avenue, and the market square. The tension is felt in the way inhabitants look at strangers. Most motorcycles, trucks, cars and houses carry improvised white flags. Some are scraps of plastic bags hung with broomsticks. As a measure of self-protection, people avoid exposing themselves in public places. In the first week of the conflict, 4,500 displaced people arrived in an urban area that houses just over 22,000 people. There are so many that no entity has tried to count the total.

Jaime Botero, president of the association of community action committees in Tibú, is one of the main sources of information on armed attacks in the rural area. The leader of these grassroots peasant organizations, he opens his cellphone and shows the WhatsApp groups where messages forwarded by the ELN arrive, listing the names, surnames, and photos of the people whom the guerrillas are threatening to kill.

He says that the current situation reminds him of the war that took place in Catatumbo 20 years ago, when the paramilitaries came to take over the region — rich in coca, onions and oil — also with lists in hand. “The method is almost the same, only now these groups have a political legitimacy that no one has been able to confront,” he says. Since the conflict intensified, the guerrillas have killed 14 community leaders like Botero and at least 20 more have been displaced. “They left me alone, but I don’t judge them. They left to protect their lives. Maybe I should do the same,” he says with a tone of resignation and his gaze lowered.

Humanitarian aid has dwindled, and displaced people are wary of institutions. “Before, large packages used to arrive, now we get leftovers and broken things,” says a leader of the La Mechita shelter. In front of the main parish church, Silvia Arocoshimana, an Indigenous Bari leader of the Association of Mothers for Catatumbo, explains that her organization is responsible for caring for some of the most vulnerable people: women and children. She takes a crumpled piece of paper from her pocket with the names of women confined in their shelters for a month. “They don’t even have sanitary pads,” she says. “They are using banana leaves or their own children’s diapers to manage their periods.”

***

The night of February 14 in Tibú was noisy and violent. After the confrontation in which Johanna and Alejandra were shot, 20 soldiers and police arrived at night to guard the commercial area and enforce the curfew decreed by the Mayor’s Office from 10 p.m. Two hours later, at almost midnight, two explosive devices shook the military barracks, the headquarters of an engineering battalion. No one knows if they were “rehearsals” by the army or an attack, but everyone agrees that there are explosions of this type every night. “One is no longer afraid of something exploding; what is truly scary is hearing the bullets,” says Doña Blanca, as she prepares to travel to Cúcuta to see her daughters.

While traveling that Saturday morning, Johanna died due to the severity of her injuries. Blanca only found out several hours later, when she arrived at the hospital in Cúcuta. She was alone. The rest of the family was still in Tibú, in the shelter. There they received the news at around dawn. They looked for photos of Johanna and begged for help to travel to Cúcuta. They hoped to find another shelter there, one that would take them in at least while they attended the funeral. Johanna died protecting the children. Her family only wants to surround her, as she did with the little ones.

Javier Báez, Alejandra’s husband, set off on his motorbike towards Villa del Río to collect the few clothes they could take from the house. “The floor is covered in blood. You can see the bullet holes in the walls. We left everything behind, I only brought the children’s clothes,” he says upon returning, his eyes filled with tears and a small green backpack on his back. He had returned to the village to work in a rice field and thus raise money to pay the 400,000 pesos (around $100) they owed for two months’ rent on the house where his sister-in-law died. But his second displacement in a month occurred in silence, without goodbyes and amid deep uncertainty. “We lost everything again, even the field that fed us.” Alejandra, his wife, survived the attack without learning of her sister’s fate. Her family did not tell her to prevent her from suffering another setback.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.