Crypto, lies and torture: Inside the scam compounds of Southeast Asia

Tens of thousands of cyber slaves are held captive in Southeast Asia’s scam compounds, working around the clock to defraud love-seeking victims through dating apps and social media

When Daniel, a guy in his 40s in a town in southern Sweden, registered an account on the dating app Tinder, things went slowly at first. “I do think I look pretty good, but my self-confidence is low and I don’t really know how to write online,” he says. But then Adele showed up. Stylish, Asian features, in her 30s. She was in Sweden to visit her aunt. Daniel quickly took a liking and the conversation continued on WhatsApp. Adele sent pictures of herself and talked about her interest in cosmetics and cooking. They planned to meet up, maybe going on a trip to southern Europe together.

Adele also told him that she had made a lot of money from cryptocurrency investments. She wanted Daniel to try his luck too. At first, he was skeptical, but after a few weeks, Adele invited him to a WhatsApp group. In the group, about 100 people discussed their successful investments and the financial analyst “Manish Aurora” gave advice. Adele persuaded Daniel to buy €100 of the cryptocurrency USDT and deposit it on the crypto platform digitalcurrencyocean.com. The money seemed to grow. But in order to get more informed advice from “Manish Aurora,” larger investments were required. Daniel decided to take a risk and invest everything he had, around €40,000 ($41,165).

But a few days later, he was warned by another woman on Tinder that he could be a victim of a scam. Daniel first tried to withdraw a small amount from the crypto platform. It went well. But when he wanted to take out the rest, his account was suspended. Adele claimed there were “taxes” that he had to pay to get his money. That was when he realized he had been cheated.

“I used to live a life with quite a lot of money. Now I was almost broke. I felt like a giant loser,” says Daniel.

What happened to Daniel is a textbook example of Sha Zhu Pan, the Chinese for “pig butchering scam.” Adele never existed in real life. Neither did the investors in the WhatsApp group. And Manish Aurora is an American hedge fund manager who, when we contact him, is in despair because his identity has been stolen and his reputation tarnished.

The pig was fattened with romance. Then it was time for slaughter.

The pig butchering scam is a relatively new form of fraud, increasing explosively since the pandemic. Thanks to investigations carried out by journalists, NGOs and researchers, we now know quite a lot about the criminal networks behind them. The scams are carried out from office complexes, usually in Southeast Asia, but also in Dubai and other places. The offices are run by crime syndicates with roots in China and with links to power elites in several Asian countries. According to calculations made at the University of Texas, these scams had a turnover of $72 billion between 2020 and 2024.

Some of the workers in the scam compounds are there of their own free will. But, according to a number of sources, a large proportion are trafficking victims forced to carry out the scams. According to a report from the UN agency OHCHR, there may be 100,000 such victims in Cambodia alone. In Myanmar, there might be another 120,000. If the numbers are correct, this could be one of the largest coordinated human trafficking operations in history, carried out by transnational crime syndicates, according to another report by UN agency UNODC.

Many are lured into the scam compounds with false promises of lucrative jobs. Raymond, a Chinese-speaking Malaysian in his 40s, got into trouble when his construction business lost revenue during the pandemic. Sitting in a café in a suburb of Malaysia’s capital Kuala Lumpur, he talks about how he was desperately looking for other sources of income. One day he saw a Facebook ad about well-paid customer service jobs at a casino in Cambodia. “They had a nice office in Kuala Lumpur and I was invited for an interview,” says Raymond.

A couple of weeks later, he boarded a flight to Cambodia. After being picked up at the airport, he was driven to the coastal city of Sihanoukville. But once inside the office complex where he was going to work and sleep, he immediately understood that things weren’t quite as he had anticipated. Armed guards stood at the entrances and he was told that he was to work with online fraud. “I wanted to leave immediately, but they refused.”

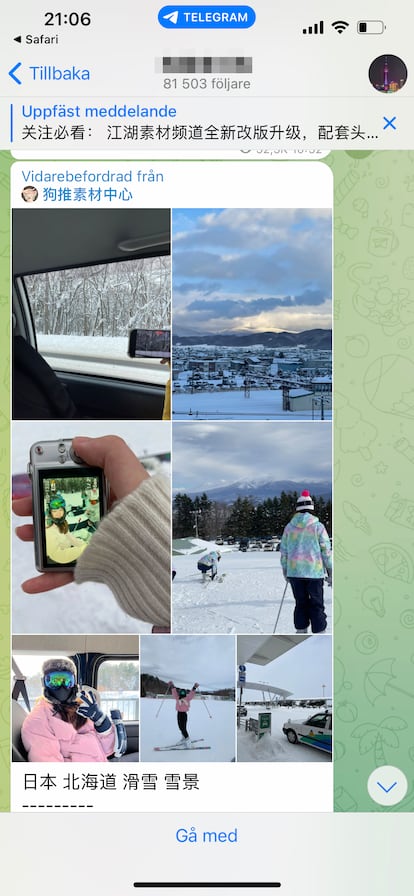

He was given a laptop and four phones with some dating and social media apps installed. After a couple of days of training with scripts for various fictional characters, he was assigned to a few European countries, trying to match with victims on dating apps and initiate conversations.

“I played characters with luxurious lifestyles who were traveling, I wrote things like ‘Now I’m in France, just got back from a shopping spree.’”

Once a romantic conversation was underway, it was time to introduce crypto investments. The characters he played were all successful investors and would first teach their victims how to trade in crypto. The victim would then be persuaded to buy the cryptocurrency USDT and transfer it to the scammers’ fake websites.

But Raymond didn’t manage to scam anyone. He started to panic. The team leader in his department had clearly demonstrated what happened if you didn’t meet your targets. Raymond saw how people were beaten severely. And how they were given electric shocks. “They did it in front of everyone else. I saw it several times.”

He began to deposit small sums of his own money to make it look like he had victims on the hook. “I realized that I had to be smart and not challenge these people.”

Months went by in captivity and Raymond desperately tried to figure out how to escape. For many, escaping from the scam compounds has meant throwing themselves out of a window and plunging to their deaths. Cambodian media reports about this phenomenon began to circulate in 2021 and have continued ever since. But Raymond didn’t jump. Instead, he began to surreptitiously use his scam phones to seek help. He found the NGO Global Anti-Scam Organization (GASO), which helps trafficking victims to leave the compounds. Raymond secretly collected information about other Malaysians in the building as well and sent it to GASO, which then contacted the Malaysian embassy in the country. It is unclear what negotiations took place after that, but one day uniformed Cambodians came to the building with a list of names. They took Raymond and a group of other Malaysians with them, and they were flown home. “That’s when my second life began.”

Andrew, another Chinese Malaysian who has come to the café in Kuala Lumpur to tell his story, escaped from captivity faster. But it came at a cost. Two years ago, he also jumped on a fake job offer in Cambodia. He first ended up as a prisoner in one scam compound, but after a few days he was sold for €10,000 to another, and then on to yet another.

Andrew was given lists of American WhatsApp numbers. His job was to play attractive women and send messages that would look like they had been accidentally sent to the wrong number. “If the recipient answered ‘No, you’ve messaged the wrong person,’ the first step was achieved,” Andrew recalls.

From there, he would establish a contact — to ultimately lead the victim into a crypto scam.

Andrew also witnessed violence against workers who failed to meet the targets. When he begged to be released after three weeks, he was told to pay a ransom. “My family paid €23,000. Then I could go straight to the airport.”

The stories told by Raymond and Andrew are consistent with hundreds of other testimonies in recent years. Last autumn, Italian researcher Ivan Franceschini, a China expert specializing in labor law, published a research paper together with colleagues Ling Li and Mark Bo in which they compiled 32 testimonies from scam compound survivors. “These are horrible stories. This is a real humanitarian crisis,” says Franceschini.

He goes so far as to call the Asian scam industry a whole new type of predatory capitalism, something never seen before. He labels it “compound capitalism.” Thousands of cyberslaves, recruited from large global groups of desperate and unemployed people to work in closed compounds. Industrial-scale data collection and manipulation of victims worldwide. “But despite its large global footprints, very few people in, for example, my home country of Italy knows what is happening,” says Franceschini.

1,000 kilometers (620 miles) from Kuala Lumpur lies the coastal Cambodian city of Sihanoukville, where Raymond was held. The city has morphed in recent years into a playground for Chinese tourists, as casinos and hotels have sprung up on a massive scale with the influx of Chinese capital.

The casino industry has close ties with the scam compounds and the building where Raymond was a captive lies near a popular beach and several casinos, in the area of Chinatown. In December 2023, the United States, Great Britain and Canada imposed sanctions — frozen assets and travel bans — on several companies and businessmen linked to this and other scam compounds in Cambodia. As recently as September last year, the United States extended these sanctions further.

Cambodian authorities have shown a somewhat ambivalent attitude towards the scam industry. For the most part, they have been allowed to operate freely, but on a few occasions, police have raided certain compounds. A few days before our visit to Sihanoukville, new media reports emerged about people jumping from windows of compounds in Chinatown, signaling that the scam operations are ongoing. With a drone it is possible to see that some rooms in the building where Raymond was held are inhabited.

The buildings are walled off. Along the street outside Chinatown, small restaurants and exchange offices operate, offering exchange of USDT — the scammers’ favorite cryptocurrency. Around a table outside, a group of men are playing cards. In a couple of places between the houses there are gates with security guards. People who pass seem to show an access card. As we walk towards one gate, we are stopped by the guards: “No, no, turn around.”

Back at the café in Kuala Lumpur, Raymond wants to forget his experiences in Sihanoukville. In captivity, he was dead inside, he says, and it took months to rebuild his life and heal. But he remembers the initial happiness when he came back to Malaysia. “The first few days, I just drove around with my car, everywhere in Kuala Lumpur, tasting freedom again.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.