The toll of Taliban laws on Afghan women’s mental health: ‘I break down at night on my prayer mat. Every day, the morality police insult me’

The new vice rules have led to a spike in depression, anxiety, and suicide attempts. According to a U.N. report, 68% of women rate their mental health as ‘bad’ or ‘very bad,’ linking their distress to the ‘systematic’ removal of women from public life

Noor, 25, a law graduate from Herat University in western Afghanistan, once dreamed of working for Afghanistan’s Attorney General’s Office. But now she takes pills to combat depression and pressure from her family to get married. “My family told me now that there’s no work or university, so it’s better to marry. I have no hope,” she says, breaking down in tears. “I receive one slap from my family and one from the Taliban.”

After suffering repeated bouts of depression, Noor sought help at the Herat hospital’s mental health ward. “I told the psychiatrist I didn’t feel well,” she says. The solution, he said, was to accept the situation. He then handed her and box of Clonazepam, a sedative pill that keeps her asleep most of the time. “Negative and suicidal thoughts increased in my head after using the medication,” Noor says, so she threw them away. “The Taliban just want to get rid of me sooner.”

The sedatives provide only temporary relief, without addressing the deeper emotional turmoil caused by the loss of education and work opportunities and the reality of staying at home with no hope for a better future. Noor’s depression was exacerbated by her sister Sofia’s attempted suicide two months ago. Sofia’s employer had accused her of violating the Taliban’s dress code and the morality police threatened her to imprison her, Noor says. “The doctors pumped her stomach that day, but she still has negative thoughts.”

Since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 following the U.S. withdrawal and the fall of the U.S.-backed Afghan republic, the Islamist militant group has reinstated its Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (PVPV) laws. This legislation, ratified in August this year, stipulate a stringent dress code on women — who must wear a diaphanous chador Hijab —, mandates segregation of the sexes in workspaces and requires women be accompanied by male relatives when traveling long distances.

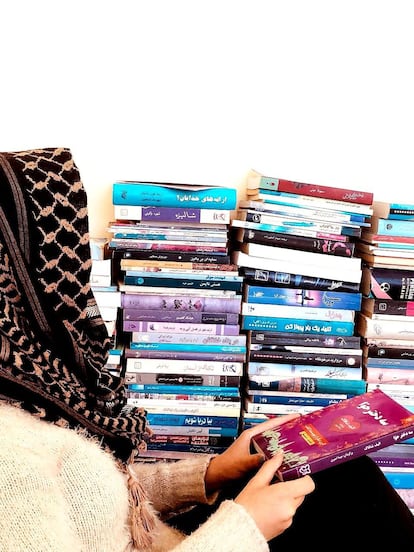

Among its 114 articles are prohibitions on speaking loudly in public. Girls have also been barred from attending secondary and university education, are now cut off from most work opportunities, and their social freedoms like going to parks and public baths have been curtailed.

The PVPV law also enables the morality police to advise, threaten, punish verbally, and arrest violators per their own judgement.

The 2024 report by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) revealed that of 888 women surveyed in 33 provinces, 68% described their mental health as “bad” or “very bad,” attributing their distress to the Taliban’s “systematic” removal of women from public life.

The Taliban argue that these restrictions align with their interpretation of Sharia law and claim the university ban is temporary, pending the establishment of an “Islamic climate.” However, internal divisions within the Taliban indicate that many hardliners oppose modern education for women. The United Nations has already warned of “gender apartheid” in Afghanistan, a term that defines the relentless harassment and how women are being gradually stripped of even the most basic rights just because they are women.

The impact of these laws has been severe. A recent U.N. report highlights that the loss of women’s influence in public and private decision-making has translated into an alarming mental health crisis. Additionally, in March 2023, 48% of respondents reported knowing at least one woman or girl who had suffered from anxiety or depression since August 2021, and 8% of respondents said they knew a woman or girl who had attempted suicide.

“Tragically, all of my patients report the same depression, hopelessness about the future linked to the inability to study or work,” says Dr. Omar, a psychiatrist at a private hospital in eastern Afghanistan who preferred to use his first name for fear of reprisal. “One 19-year-old girl told me she’s suffocating in her home, thinking of the prolonged school ban.” That patient was 16 when the school ban started, explains Omar. This issue continues to impact women’s mental health, as most of his patients are between 16 and 30 years old. And the figure continues to grow. The number of patients who visit him has tripled since the Taliban took over, he says.

Beyond the mental and physical impact

Decades of conflict and instability have left many Afghans vulnerable to anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. The social stigma attached to mental illness further complicates issues. By the end of 2021, half of Afghanistan’s 40 million people were estimated to be suffering from psychological distress, according to HealthNet TPO, one of the largest health NGOs operating in the country.

Dr. Ghafoor, a psychiatrist at Herat hospital’s mental health department, told EL PAÍS that the Taliban has prohibited his clinic from sharing patient data with the media, but said that the mental health ward receives 250 patients daily and the psychotherapy department serves 20 to 25 cases of suicide or unconsciousness every day.

He explains that 80% of his patients were always women aged between 16 and 45, but that this number spiked by 25-30% just five months after the Taliban’s return to power. “After being banned from education and work, they were under pressure to marry because the family can’t bear the economic burden of supporting them,” says Ghafoor.

“In many instances, the morality police interfere with our work, especially in the psychotherapy department,” Ghafoor explains. “They asked me why women without injuries are hospitalized, implying that only people with physical injuries could be considered patients.” Due to this constant pressure, he was forced to discharge patients before they were ready. “It was humiliating for the patients, and distressing for me as a professional,” he says.

After mounting restrictions on his work, and rampant morality police interference, he left Afghanistan. The mental health department is now mostly run by interns, according to patients.

Wranga, a single woman from eastern Afghanistan, usually picks up her young nephew before commuting to work if her brother isn’t available. The 31-year-old is only allowed to travel long distances if accompanied by a close male relative to comply with the Taliban’s morality law.

But a few months ago, when her brother and another of her nephews weren’t available, she took a female relative along. When she reached a Taliban checkpoint, morality police with AK-47s slung across their shoulders scanned the car and reminded her of the rules about male guardians. “He asked me to get out of the vehicle,” Wranga recalls.

When she tried to explain, she was told “shut up, we don’t talk to you” and the soldier interrogated the driver instead after threatening to flog Wranga. “They treated me like a slave,” she says.

Wranga is one of the few women able to work at an international NGO that provides health and livelihood support to rural Afghan populations, which represent over 73% of the total population of 42 million. She is also the sole breadwinner in a family of 14. Both her mother and brother are hospitalized for chronic illnesses. Like millions of Afghan girls living under Taliban rule, Wranga’s sisters have no access to education.

“I break down at night on my prayer mat. Every day, the morality police insult me for different reasons,” Wranga says.

“Anyone who talks about the bans risks being arrested or disappeared,” says a female activist from Kabul, who preferred to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal. “All our advocacy efforts failed to make tangible change for women.”

While Taliban argue that their restrictions are “temporary,” they recently shut down a medical institute teaching women midwifery and nursing, a blow to the Afghan health sector which is suffering a deteriorating economic crisis and shortages of international donors who left Afghanistan following the Taliban takeover. The group has also announced plans to ban international NGOs, a move that could impact women like Wranga. “They are now coming after my last hope,” she laments.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.