No region in Lebanon is safe from Israeli bombing

The IDF has launched strikes in the only area of the country that until now was considered relatively safe from the offensive, due to its distance from the southern front and Israeli territory

There is no safe place left in Lebanon. Rescue teams finished their efforts early Tuesday morning to find victims of an Israeli airstrike the day before in Ain Yaaqoub, in which at least 14 people were killed and dozens wounded. The village, 77 miles north of Beirut, is in Akkar, Lebanon’s northernmost region. It was, until now, the only one that had not been attacked and was considered relatively safe, being over 120 miles from the border with Israel, the main front line of the fighting. That safety has turned out to be a mirage.

Even before Israel launched its massive bombing campaign on September 23, the narrative of Israel’s leaders and military command was that their enemy was not Lebanon or the Lebanese, but Hezbollah, the Shia party-militia that has been shelling northern Israel in solidarity with Gaza since October 2023. Since then, Israeli strikes have killed 3,365 people and injured 14,344 in Lebanon, according to the latest death toll released Wednesday by the Ministry of Public Health. With the deaths in Ain Yaqoub, that toll now comes from all regions of the country.

When Israel launched its ground offensive in southern Lebanon on October 1, its army described the operation as “limited, localized and targeted ground raids” against militia targets. However, Israeli soldiers have not refrained from destroying around 40 villages near the southern border. Their attacks have also destroyed at least 40,000 homes.

This destruction has not always been due to bombing or artillery attacks, but because the infantry has blown up houses and infrastructure in these towns. This has been made clear by the videos they themselves have posted, such as those showing the destruction of most of Meiss Ej Jabal, a town located next to the Blue Line, the unofficial demarcation drawn by the United Nations between Israel and Lebanon. In some agricultural fields in the town, soldiers have planted Israeli flags.

A video released on November 8 by Israeli soldiers showed them, in the same town, setting fire to the red and white Lebanese national flag, rather than the yellow Hezbollah banner. Like the casualty figures and the extent of the destruction, these images compromise the official Israeli narrative that this war is directed only against the party-militia; hence Israel has been forced to disavow these soldiers. The army’s Arabic-language spokesman, Avichay Adraee, posted a tweet on Saturday saying that this act “was not in line with the objectives” of what he called “military activities” in Lebanon. The spokesman did not, however, announce any sanctions against the soldiers.

Israeli strikes had initially focused on the Shia-majority areas where Hezbollah has its social base: southern Lebanon, the Beirut suburb of Dahieh — which was again heavily bombed on Tuesday and Wednesday — and the eastern Beqaa Valley. By the end of October, the offensive had already spread to other areas of the country. The UN coordinator in Lebanon, Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert, warned at the time that “the scope and intensity of the exchanges of fire were continuing to expand.”

With the bombing of Ain Yaaqoub in Akkar, this circle has closed, reaching all regions of a country where 1.2 million people displaced by the war — one in five Lebanese, most of them Shia — have sought refuge outside their places of residence.

Books and shoes

Almat is another of those remote towns far from the border where 10,000 displaced people have arrived seeking safety, its mayor, Ali Awad, explained to this newspaper on Monday. The town, whose inhabitants are mainly Shia, is located on a hill 30 miles northeast of Beirut, in a region with a Christian majority.

On Sunday, one of its residents, Nur, saw two Israeli warplanes fly over. “I knew they were going to attack my village, but I didn’t know they were targeting the house next door,” he explains. In that house, now reduced to rubble by a missile, many children, displaced from the Beqaa Valley, were sheltering. Of the 27 dead that rescue teams pulled out from under the rubble, seven were children. Five arrived dead at the emergency room of the nearby Notre Dame Maritime hospital. “They were between five and 10 years old and completely disfigured,” explains nurse Rosie Khoury by phone.

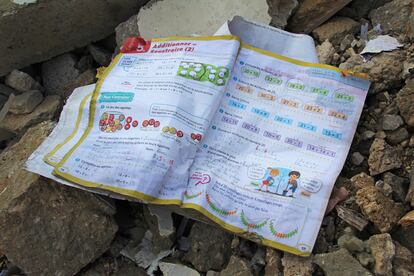

A math book with addition and subtraction lies in the ruins, with the name of its owner written in childlike handwriting: Talea Safiedine. Not far away, the rubble is mixed with a pile of shoes: all mismatched, most of them small. Some adorned with little flowers and glitter hearts. A packet of menstrual pads with the plastic torn off sits in the middle of this place of desolation.

“Women and children lived here, and we are almost 125 miles from the border with Israel. Was it necessary to send an F-35 [warplane] to bomb the house?” the mayor wonders aloud as he picks up a pair of children’s trousers with a stick. In the house, he exclaims, “there were no Hezbollah weapons. The television channels came and recorded everything while we were removing the rubble with a bulldozer: Where are these weapons?”

When Israel justifies its attacks, which is not always the case — as in the case of the bombing of Almat — it usually claims that the buildings targeted were sheltering militants, or that they were used to hide Hezbollah weapons.

“Even if it were true that a fighter was hiding here, couldn’t the Israelis have just killed him, without deleting three families from the civil register?” the mayor asks. He then shows on his cell phone a photograph of a list of the names of the dead, members of the Al Karsifi, Al Hussein, and Zrik families.

“Jews suffered the Holocaust in Europe, but what is happening here is another Holocaust,” says Awad. He believes that Israel “is attacking places like Almat to kill as many women and children as possible and to spread terror.” He also believes that this is to prevent the Lebanese from “accepting the displaced.”

The fear of such rejection has a real basis. Bombings such as the one that killed 21 people in a house being rented by displaced people in the predominantly Christian town of Aitou, some 60 miles north of Beirut, in late October have fuelled this suspicion. Although incidents over the reception of displaced people between the different religious denominations — the majority being Christian, Sunni and Shia — have so far been occasional and never serious, some Lebanese do express fear that their Shia compatriots who have fled their homes could attract Israeli warplanes and missiles.

The population of Akkar, the northern region that was the last in the country to suffer a massacre for the first time, is predominantly Sunni and is also home to Orthodox Christians. Considered the breeding ground for the Lebanese army, the presence of soldiers and its distance from the border with Israel probably helped convince some Shia displaced that they would be protected there. “Here, with so many soldiers, I feel safe,” Fatima, a Shia who had to flee Dahieh and found refuge in the town of Akkar al-Atiqa, told this newspaper on Saturday.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.