José Rubén Zamora: ‘My two years in prison explain Guatemala better than my 30 years in the press’

The former director of ‘El Periódico’ speaks with EL PAÍS, after being released from the military penitentiary where he spent 813 days. ‘I feel very happy, as if I’ve been reborn,’ he says

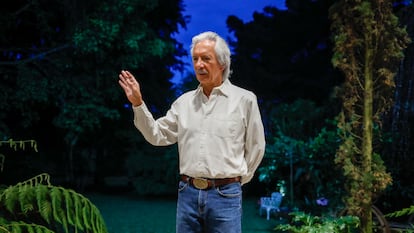

On Halloween night in Colonia El Carmen — a gated community in the south of Guatemala City — children dressed in costumes go door-to-door, trick-or-treating. As the group moves forward, parents following behind notice a tall man with white hair and a thick moustache. He’s watching the kids from behind the gates of his house: he’s guarded by two police officers.

The parents step up to the gates and greet him: “We came to express our joy that you’re here,” an excited mother tells him. “God bless you.” He thanks them and — with an embarrassed voice — apologizes for not having any candy to offer their children.

If his release from prison has taught 68-year-old José Rubén Zamora anything, it’s that many people love him. This has been made clear to him insistently over the last two weeks by dozens of people he has met: from the politicians, ambassadors, diplomats and journalists who visit him, to the neighbors who stop him when he goes out for his daily walk. He’s even well-liked by the officials at the court where he goes to sign his conditional release. When passersby saw him having coffee with some friends on a terrace in the Guatemalan capital, they stopped to greet him.

“It was striking because, for three hours, we couldn’t talk, because of all the people who stopped by to say hello, to give me a hug, to congratulate me… I find it hard to live with all of this attention, because I’ve always been very shy,” he confesses. But he senses that he’ll have to get used to it, at least for the next few months.

The 813 days that the founder of the daily El Periódico spent in the Mariscal Zavala military prison — where he was tortured — have made him a symbol of resistance against the criminalization of journalism and the fight against corruption in his country. Zamora was released from prison on October 19 to comply with a house arrest order issued by a judge, who ruled that the preventive detention time allowed by law had been exceeded. When this decision was made, he had been imprisoned for more than two years, accused of money laundering and obstruction of justice. He was charged with these crimes during the administration of former president Alejandro Giammattei (2020-2024). Although Zamora was initially sentenced to six years in prison for the first charge, the ruling was ultimately overturned due to procedural errors.

The journalist has always denied the accusations and has attributed them to persecution due to investigations carried out by the media outlet he founded — El Periódico — that revealed corruption in the Giammattei administration. The journalist’s hypothesis has been supported by various international organizations that have analyzed the case and have also denounced “serious procedural violations.”

Today, Zamora recognizes the fundamental role of pressure from the local press and foreign organizations in demanding his release from prison. “They’ve all fought and kept my case alive. I don’t have enough time in my remaining life to be able to return all that I owe them for everything. Because of them, I’m out [of prison],” he sighs, in an interview with EL PAÍS at his home.

Worn out, far from his family, penniless, but happy

Like José Rubén Zamora himself, the three-story house with a lush garden — where the journalist is serving out his preventive detention — has been a front-line witness to Guatemala’s contemporary history. Built in 1950 by his grandmother — Doña Carmen — and his grandfather, the journalist Clemente Marroquín (who became vice president), all kinds of politicians, artists and intellectuals have passed through it over the last seven decades.

“There was always political pluralism here,” Zamora notes. He gives the example of the day he got married. “It was funny, because a journalist who wrote about my wedding — here at the house — titled it The Wedding of the Century. But the only people who didn’t appear in the story were the bride and groom. He talked about everyone who attended, how all the people in Guatemala came together here, even if they were enemies.”

But the good times didn’t last. As the founder of media outlets that revealed the dark side of the powers in Guatemala (before El Periódico, he created Siglo Veintiuno), Zamora has been the target of threats, attacks and raids for decades. “They simulated my execution four times here. The last time, in the garage, they fired a gun and I said: ‘I’m dead and that’s it,’” he recalls. That was in 2003. It led to his family’s first exile. His wife and the youngest of his three children returned, but last year, they were forced to flee to the United States again, fearing that they too would end up in prison, to put pressure on the journalist.

Away from prison, Zamora says he feels physically “worn out,” but emotionally strong. “I’ve always loved being here, in this house. It means a lot to me. And even though it’s empty, even though my family and my children aren’t here, I feel very happy,” he says. Among the after-effects of more than two years confined in a tiny, dark, dusty cell — where he suffered from insect infestations and was tortured — are joint and back pain, a mild but constant sinusitis (due to the fungus in his cell), as well as poor circulation in his legs. “My toes were stuck together,” he explains.

Despite his ailments, he says that he still feels strong. “Over the last 15 months, I felt healthy and I learned to enjoy my solitude quite a bit and to live with what I had at hand.” And, even though he’s still getting used to his new situation, he says he’s “very happy.”

“It’s as if I’ve been born again,” he reflects. But Zamora knows he must face new challenges, such as living far away from his children, without any money. His family was forced to sell their cars and some properties to be able to pay legal fees and the salaries of workers at El Periódico, which was shuttered in May 2023 due to pressure from the Giammattei administration.

“Learning to live without money is another challenge,” Zamora confesses. He now depends on the money his children send him from the United States, as well as on friends who help him get around the city. “I don’t have the resources, but I’m going to figure out what I’m going to do next. I have to start generating [an income].”

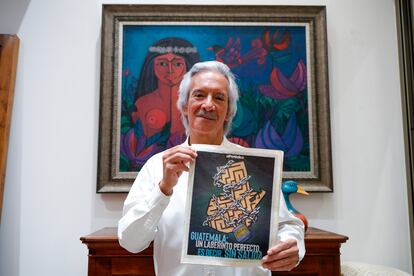

Amidst this situation, there’s something he’s been reflecting on lately that impresses him. José Rubén Zamora believes that — more than any of his numerous publications — his time in prison better portrays what he’s been trying to convey throughout his career: that Guatemala is a “labyrinth with no way out.” This is how he describes his country, which has high levels of impunity.

In recent years, hundreds of judges, prosecutors and journalists who fought against corruption have ended up in prison, or in exile. “I think that these two years in prison allowed me to contribute more to people in Guatemala and abroad. I was able to help them see Guatemala as it is, much more than during the 30 years I was in the press, where I was always repeating that we’re a narco-dictatorship that co-governs as an alliance of interests to hold us hostage.”

President Arévalo, Guatemala and the future

One of the first visits Zamora received upon arriving home was from President Bernardo Arévalo, who came to power in January 2024 under the banner of fighting against corruption. The president — who has always described Zamora’s case as “political persecution of the press” — improved the journalist’s conditions in prison and promised that his human rights would be respected. “It was a personal visit to express his satisfaction and his joy that I was at home. I was very grateful,” says the journalist, who describes the president as a decent man, a centrist and someone who doesn’t pose a threat to the system.

Like Zamora, Arévalo and his party — the Seed Movement — have had to face legal proceedings. The charges come from the Attorney General’s Office, which is headed by Consuelo Porras and Rafael Curruchiche, two officials sanctioned by the U.S. State Department, which included them on its list of corrupt and anti-democratic actors. For this reason, the journalist believes that Arévalo runs the risk of ending up in prison like him. Especially if his popularity continues to decline.

“Curruchiche said that the most corrupt official in Guatemala is President Arévalo,” Zamora warns. “They’re going to speed up his legal process.” And, while he says the president is optimistic and confident that corrupt officials have less and less power within the state, he also believes that Arévalo is facing a difficult scenario. “The attorney general has a challenge similar to [the one faced by President] Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua and [Nicolás] Maduro in Venezuela: that, if he falls, he’ll be prosecuted. And so, those who lead the Attorney General’s Office will do everything possible so that whoever replaces them is someone who will protect them in a country whose hereditary DNA is impunity and corruption.”

For Zamora, his time in prison hasn’t only distanced him from his family and left him peniless: it has also meant the closure of his media outlet that — for decades — acted as a counterweight to power. “It made me happy — not just with Giammattei, but with all the presidents — to see that a small newspaper was exercising a small counterweight. I was able to do that in a country where there’s no justice, where there’s only impunity,” he says, in the living room of his house. Just a few feet away from where he sits, in the garage, dozens of boxes protect the accounting files and investigations of El Periódico. This is the last physical vestige of a media outlet that once had hundreds of employees and gave Zamora the respect of a part of the population of his country, as well as international prestige.

For the moment, there are no plans to set up another media outlet. And Zamora is aware that returning to prison is still an option. In fact, prosecutor Curruchiche has asked that his house arrest be revoked, alleging that the journalist is a flight risk. But Zamora emphasizes that he has no intention of leaving the country, except to visit his family — something he would do only with the permission of a judge. “Last Friday, I had a hearing and I didn’t have to go. But I still went, so they could see that I’m not leaving Guatemala. I’m never going to leave. And, if they want me to leave, the local fascists will have to expel me.”

Zamora sees this stage of his life as a final victory in his long road of resistance. “They haven’t defeated me. What they wanted was for me to feel ashamed and ridiculed. They haven’t succeeded. Fortunately, I haven’t felt ashamed, or that I’ve done anything against the law,” he says.

Before saying goodbye, he reiterates: “If they take me back to prison, I mustn’t be ashamed.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.