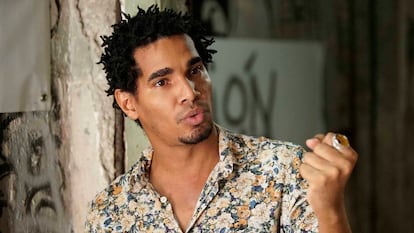

Luis Manuel Otero, Cuba’s most famous political prisoner, speaks from jail: ‘I’ll either be a martyr, or I’ll leave the island’

Three years after the July 11 protests — the largest in Cuba since the early years of the Revolution — the dissident artist speaks with EL PAÍS

The artist — Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara — has been given a few minutes to make his Tuesday call. He grabs a public phone in the Guanajay Maximum Security Prison, located on the outskirts of Havana.

At 1:05 p.m., the performance artist answers some questions from EL PAÍS for as long as the prison authorities allow. Otero Alcántara is the most famous political prisoner in Cuba, and — as he puts it — “the most dangerous” for the government. When Cubans, tired of their leader, thought they could haven’t one of their own, the figure of Luis Manuel — a self-taught artist — emerged from the impoverished and majority-Black neighborhood of El Cerro, in Havana.

His catchphrase — “we are all connected” — his challenging performances, his multiple arrests, his hunger strikes and, finally, the destruction of his house made him a subject of interest among Cubans, both those on the island and in the diaspora. His residence also acted as the headquarters of the well-known San Isidro Movement. Formed in 2018, it’s made up of Cuban artists, journalists and academics, who protest the censorship of artistic expression.

In September 2021, his face appeared among Time magazine’s 100 most influential people, alongside the Russian opposition activist Alexei Navalny, the pop star Britney Spears, the tennis player Naomi Osaka and the Puerto Rican singer Bad Bunny. “His unignorable fight for freedom of expression and his uncompromising stance against autocracy reveal the power of resistance,” wrote Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, in the pages of that publication. “His life, behavior and expression as a whole are so powerful that they can resist the esthetic and ethical degeneration of authoritarianism.”

The last time Otero Alcántara walked through the streets of Havana was on July 11, 2021.

That was the day of the largest anti-government demonstration in Cuba since the early years of the Cuban Revolution. Thousands of Cubans took to the streets, while thousands ended up becoming political prisoners.

Three years after he was jailed — with a sentence of five years for the alleged crimes of contempt, insulting national symbols and fostering public disorder — Otero Alcántara recalls the moment in which the Cuban police arrested him on Paseo del Prado, a major promenade in Havana. He was on his way to join the demonstrations. He says that the day began as one of the happiest in his life.

Question. Do you have any particular memories of July 11, 2021, the last day before your imprisonment?

Answer. Yes. It had been a good week. We were working, putting together a kind of first aid kit to bring medicines to Cuba, due to Covid-19. And, that day — like many others — I was also surprised that there were that many people on the street. [Initially], I believed that what was happening was normal. Around that time, it was relatively common for people to go out to protest, because there was no water. But these were small protests. That day — at the headquarters of the San Isidro Movement — many people told me: ‘Luis Manuel, gather people, gather them.’ And I’ve never really believed that I have the power to summon a crowd, in the way that people believe I can.

I went into the streets, into the daylight, without a phone, disconnected from everything. That was one of the happiest days of my life. In fact, when [the police] detained me and put me in a patrol car with three officers, the patrol car’s radio was announcing: “Hey, thousands of people are coming down San Lázaro Street, thousands of people are coming down Trillo Park.” And, at that moment, I said: “Well, it looks like things have really gone down.” And the patrol driver told me: “But you’re not going to be there.” And I told him: “I don’t need to be there, I’ve already done what I set out to do.” Next to me, there was a young police officer wearing a face mask. He made a sign, as if to tell me that “we’re connected.”

Q. At one point, you became the best-known — and, probably, the most-followed person — in all of Cuba. What do you think led to you occupying such a space?

A. I’ve never seen myself as a handsome guy, [even though] some people see me as being a bit handsome… the same thing happens with this. I first started out with the need to make art: it’s an illness, it’s my vice, something that I believe in. I believe in that, in the love of others. Since I was a child, I always had that worry: being worried about others, worried about the child who didn’t have anything, even though I didn’t have anything. If I had a single peso, I split it with the person next to me.

I have that in me, and it’s not a curse, but sometimes, it’s a kind of non-blessing, because being worried about others means that I’m not in Hawaii, living like another type of artist of my generation. But there’s a responsibility towards the other that never leaves me. I’m one of the happiest guys in the world. My happiness comes when I do something for others. And that comes intrinsically, it’s within me. From that place, I make art that’s committed to reality. And, many times, that same reality has tested me.

I went to Madrid. I could have stayed. I could have chosen the path of easy art, of painting flowers, or making a type of political art that was simply a discourse and that didn’t activate real content within reality, that didn’t shake up reality. Art can alter reality if you, as an artist, want it to do so. Otherwise, [your art] becomes a political caricature. With [that mindset], I continued working. That’s when I realized that many of us were connected, we were on the same level. Also, due to a certain madness that I have, I resist aggression differently. And also because of the leadership vacuum in Cuba, many people put me in that place. It was a mix of things: a certain charisma that I think I have, the artwork that makes an impact, a commitment to people.

Contemporary reality isn’t rigid. And being an artist, having certain freedoms, allows me to encompass a little more than if I had been a politician… something that implies behaving in a way, dressing in a certain way. I love freedom above all.

Q. What does freedom mean to you? How imprisoned are you, how free are you?

A. I’m in prison, of course. Freedom is a construction, in the sense that it’s built on a day-by-day basis. You’re not free, you’re a little more free than yesterday, a little less than tomorrow…

Within that construction, you’re always losing possibilities. For example, I have to go to bed at a certain hour, get up at a certain hour. I live behind bars, I can only speak [on the phone] twice a week. Out on the streets, you can always chat, you can drink cold water, you can have sex. In the spaces that tell you that “you are not free,” all these [possibilities] are taken away from you. Here, [in prison], there’s someone who decides how you dress, how short or long your hair is, how you shave. You lose all of these freedoms when you’re imprisoned, as I am.

Luckily, I can paint in here. I think it’s one of the few spaces where I have my own freedom. [The authorities] didn’t want to [interfere with this], because if they were to do that, they know that it would kill me. I think that, thanks to art, painting, drawing, I’ve been able to survive these three years. I continue to draw, paint, make things. I have many ongoing projects, dealing with things that take me back to my childhood: childhood traumas, sex during childhood, mistreatment by teachers. In three years, I’ve done a lot. I come up with an idea probably every week. Without [my art], in this confinement, I would be like a sparrow: I would have thrown myself against the bars a long time ago.

Q. In the past, you’ve said that you’ll accept exile — leaving Cuba — in exchange for being released. But if you were to serve your entire sentence, would you still leave Cuba?

A. First of all, two years ago, I agreed to leave as an option to continue working. Working as a form of struggle, of course, because I’m a fighting animal. I’m going to continue fighting, not only against [the authorities], but against all evils: against racism, homophobia. Art is the tool that God — or whatever’s out there — provided me as a human being. From that point onwards, I’ll be an eternal fighter — and an eternal resister — in the face of what I believe is wrong.

I never thought of leaving, but the regime has insinuated that there’s no option for me to walk through the streets of Cuba, because of the threat they’ve made me believe I am, or that people believe I am. I realize that the art I make represents a danger for them. The options are between exile, or remaining [in Cuba] and always being in trouble.

Just as they built me these five years out of nothing — out of falsehoods — they could easily build another five or 10 years, it wouldn’t be an issue for them. So, I choose exile. But I don’t want to leave Cuba. That’s the big problem: I’ll either be a martyr, or I’ll be outside of Cuba. I can’t find any other way out.

Q. How do you imagine the day you finally get out of prison? What’s the first thing you plan to do?

A. [In my mind], the day they release me seems like a work of art, a rigid canvas. I imagine that I’m going to go through a complicated process, lasting two or three days, going through different places until I reach exile. Of course, that’s in case they release me soon, because if one more day passes [beyond my sentence], I plan to go on my big hunger strike.

I really don’t want to leave Cuba. I’ve never wanted to leave, but it’s an option to be able to continue working and doing things. In the worst case scenario, I’ve always thought of becoming a martyr: having a school named after me, having the name of the San Alejandro school replaced with Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara.

If things turn out ok, if I make it out alive, that day will be one of the happiest of my life. I’m not going to hate anyone. It’s going to be a reunion with all my friends, with my family, being able to breathe, being able to walk, being free. I’ll let people see the work I’ve done these past three years, because, of course, the only thing I’ll leave here with is all the artwork from this time.

This confinement could end in many ways. My thought is of a happy ending, in which I reunite with all the people I love and continue to work. Then, the great performance will be to isolate myself for three days… to get rid of all the hatred, all the darkness, tear off all my clothes and only keep [the Cuban] flag.

Q. In the three years that you’ve been in prison, Cuba has further deteriorated. Do you know that you’ll probably return to a country that’s even worse-off than before?

A. Of course. I’m a guy who’s concerned with the Cuban reality. I can’t talk to you as I would have talked to you three years ago, because I’m a very down-to-earth guy; I like to walk the streets and feel the pulse of what’s happening on the ground. By looking at people’s faces, I’m able to see what’s happening. I haven’t checked in for three years: I get a visitor once a month. I ask questions, people around you make comments. But that talent that I think I have — to be able to walk through the streets and perceive how the Cuban ecosystems work — I’ve been cut off from that.

I know that the reality is getting worse. And that’s why I know that, every day, I’m more dangerous. That’s why they’re not going to let me walk through the Cuban streets. I no longer have the fear that you’re supposed to have of prison, of a space like this, which I already see as relatively normal. My body has already adapted. They know that I’m dangerous: they’re not going to kill me, because they know that becoming a martyr is part of my reality.

The other thing is that this cycle — as an experience — no longer generates anything for me. [I’ve been arrested many times]. Before this, I would go into prison, I would come out of prison… it no longer impacts me. Now, all I think it does is help me be even more creative.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.