‘If you don’t have money to go to Europe by boat, you try to get there by starting a relationship with a tourist’: Sex tourism plagues Gambia

Economic inequality is driving European tourists to the African country who come seeking sun, but also sex. Its government’s plans to attract ‘quality tourism’ have failed to take off

“We’re going to take a walk on the beach,” shouts a Dutch woman, smiling widely before she disappears among the dunes, kissing a Gambian who appears to be 30 years her minor. Her party, composed of three other Dutch tourists and three young locals with dreadlocks, seem neither surprised nor bothered.

Staff at Justice, a café-restaurant with an open patio situated alongside a dirt road near the coastal town of Serakunda, watch the scene in silence. The night security guard at the nearby Bamboo Garden hotel is more talkative. “It hurts me to see our brothers and sisters being exploited,” he says. Every evening, he sees Dutch, British and German tourists leave their room alone, only to return later that night with a Gambian man or woman. “But what can we do?” the caretaker asks with a shrug.

Officially, visitors’ guests are not allowed to sleep at the hotel, but if tourists slip some money to the receptionist, they turn a blind eye. In the majority of cases, their guests leave that night. “But sometimes, girls come to the front desk crying,” the guard says, sighing. And although the girls say that they’ve been treated rudely, or worse, they hardly ever call the police. “The hotel’s customers pay them not to talk, and it’s over. It doesn’t feel good, but we have to be on our customers’ side. If we aren’t, they’ll fire us,” says the guard.

The tourists staying at the hotel, with the exception of one young married couple, are largely older couples and men and women who are traveling on their own. Many travelers visit the Smiling Coast of Africa via German tour agency TUI, whose spokesperson does not deny the existence of sex tourism in Gambia, but points out that agencies are not obligated to “tell travelers what they have to do on their vacations.” They add that TUI “mainly transports couples and families on its aircraft” who are going on beach vacations. Its all-inclusive travel packages are very popular; around the time that rains and cold weather arrive in northern and central Europe, tens of thousands of Dutch people visit the tiny country on western coast of Africa every year.

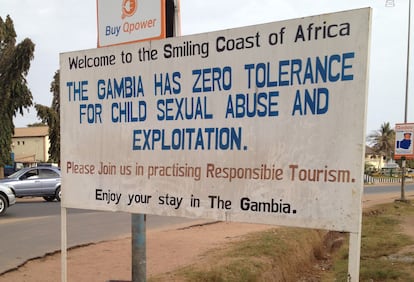

The sex tourism that attracts some of these European visitors to Gambia is becoming more and more troubling to Gambians. “What we want is quality tourists,” Abubacarr Camara, director of the country’s office of tourism, told The Telegraph last August. “We want tourists that come to enjoy the country and the culture, but not tourists who come for sex.” Hamat Bah, Gambia’s minister of culture and tourism, also stated in a television interview: “If you want a sex destination, you go to Thailand”; a statement for which he later had to apologize.

The proposals that politicians have put forth to attract what they call “quality tourists” to Gambia “have come to nothing so far”, says activist and musician Ali Cham

Politicians have put forth some proposals to attract what they call “quality tourists” to Gambia, like the subsidized construction of ecological refuges, and to prevent sex tourism, through more severe penalties for foreign sex criminals. But these initiatives “have come to nothing so far,” says activist and musician Ali Cham. The svelte Gambian, who wears a goatee and long dreadlocks, has been trying to draw attention to the negative consequences of sex tourism in his country for years through music and activism. “European tourists take advantage of economic inequality,” says Cham. “Unemployment is a huge problem and it make them vulnerable to tourists who come here and tempt them with their money. It is not a just situation,” he says. Tourism is an important industry for Gambia — it makes up 15.5% of GDP, according to the World Bank — which is one of the smallest and most densely populated countries in Africa. More than half of its 2.5 million residents live in poverty, according to a 2021 report by the same organization.

‘It’s ruining an entire generation’

Cham, whose artist name is Killa Ace, performs regularly in entertainment venues along the Senegambia Strip, a small section of highway that is home to many restaurants and clubs. He calls it the epicenter of Gambian sex tourism. “Couples don’t even try to hide it,” he says. “Here in Serekunda, sex for money has become the norm.” Cham says this phenomenon impacts the entire community. “It paves the way to other kinds of abuse,” he explains. “Pedophilia is also getting to be more common. White men rent villas and let the bumsters (a name for men who run sex tourism) bring them kids. That’s how sex tourism is ruining an entire generation.”

On the beach near the Senegambia Strip, a few tattered flags flap in the strong western wind that kicks up the fine sands and splashes the ocean onto the shore. The flag belongs to a makeshift juice stand built with driftwood on the dunes. A muscular boy with a white shirt and a small yellow swimsuit, who introduces himself as Nana, tries to attract clients. “Good afternoon!” he shouts, trotting across the beach. With a big smile, he hands over a laminated, sun-bleached menu that offers various kinds of juice.

— “Can you tell us something about how sex tourism works here?”

— “Let’s go sit down,” he responds, the smile disappearing from his face.

When the other young people at the juice stand figure out that the conversation has turned to sex tourism, half of them leave. “I don’t feel like doing that,” says Demba, a tall boy with short dreadlocks. “The biggest culprit is the huge inequality between us and the tourists,” says Nana, as he sits down in the sand. “The rich women, but also sometimes the men, they come up to you and ask for a massage. That’s how it all begins.”

Demba, who continues listening from a distance, joins the conversation. “If you see me disappear in the dunes with a woman who could have been my grandmother, you know something’s not right in my head,” he says, angrily. Still, he has had some relationships with European women. Demba insinuates that he’s trying to get to Europe via this strategy. “There’s no work here,” the Gambian explains. “If you don’t have enough money to get to Europe by boat, you try to get there by starting a relationship with a tourist,” he concludes.

Another kind of tourism

At 28 years old, Jalamang Danso has heard this kind of reasoning too many times. “Even if you’re educated, it’s nearly impossible to find work in Gambia,” he says. He’s been lucky. 186 miles up the Gambia river, near the river island Janjanbureh, he brings tourists by boat and car to the area’s towns, islands and extensive baobab forests. “The majority of them come for the sun, the sea and the sex. Gambia has much more to offer,” he says, contemplating a motor boat that advances slowly along the river.

All kinds of creatures look for food along the river’s banks, which are covered with mangroves and palm trees. The air is heavy and sweet. Gambia, an elongated country that runs along the river from which it got its name, is home to more than 600 species of birds, crocodiles and hippopotamuses. “But today we’re looking for Ninki Nanka,” whispers Danso, his eyes aglow. For centuries, the Gambians who lived along the river have told stories of this mythic monster, who is similar to that of Loch Ness. “My tribe believes it is a mix of a giraffe and a hippopotamus. Anyone who looks it directly in the eyes dies in the act,” he says, mysteriously.

The river monster is the namesake of the tour that Danso and dozens of his peers offer through the inland Gambia. The Ninki Nanka Trail was created two years ago. After the Covid pandemic, Danso and other Gambians in the tourism industry have worked to expand the kinds of activities they offer. “We have mapped out a route that passes through six small inland river villages,” the guide says with pride. Hundreds of travelers visit small museums that display traditional masks, learn to work with clay in picturesque villages and navigate the river on boat safaris. The activities are run by young guides who are part of the Ninki Nanka Trail parent company. But despite this success, Danso receives zero support from the state. “They’ve been saying for years that they want to diversify tourism, but they don’t do anything to make that happen,” he says.

Just then, his attention is drawn by the snapping of branches. The small boat’s captain immediately shuts off its engine and steers towards shore. What appears among the foliage is not the river monster, but a chimpanzee. The animal hangs from a tree, dipping its chest into the river to drink a few sips of water. “Amazing, right?” asks Danso, visibly impressed, even though he has to see these animals often. He wants to show this sight to more tourists. “That would give a big push to the local economy,” he says.

The local economy, but also the national economy, would do well with such a push, Danso says. According to the guide, even the more touristic coastal region would benefit from the arrival of visitors who eschew tour agencies. “The entire ocean is in the hands of foreign tour operators,” he says. Many tourists even eat imported food, in restaurants staffed by people from other places, which means the money that is generated does not stay in Gambia. “Nowadays, the average Gambian barely earns anything from all these tourists who are visiting our country,” says Danso. “Only through sustainable tourism development can we put an end to the exploitation and humiliation.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.