Viktor Orbán fuels ethnic conflict with Ukraine’s Hungarian minority

Transcarpathian Oblast — the westernmost and safest region of Ukraine — faces tensions between its communities. This conflict has been fueled by Budapest, which is threatening to veto Kyiv’s attempt to join the EU

The clocks in the Berehove region of Ukraine are one hour behind the official time of the rest of the country. “We operate on Budapest time,” explains Józef Choboya, a local retired historian. “Why do we do it? Because here, everyone [observes] European time,” notes Robert Nagi, a soccer coach from the village of Badalovo, on the border with Hungary.

Choboya and Nagi are members of the Hungarian community in Ukraine, in the Transcarpathian province. Recently, the rights of this national minority are putting the future of Ukraine in check. The prime minister of Hungary — the ultranationalist Viktor Orbán — is threatening to use his veto power to prevent Ukraine from entering the European Union or NATO, so long as this Hungarian community doesn’t receive more autonomy.

Experts warn that the Hungarian populist leader — an ally of Vladimir Putin — is fueling a potential conflict between national groups. He’s pulling Kyiv into what academic Dmitro Tuzhanskii has defined as “an ethnic trap.”“The issue of national minorities has been decisive in the latest decisions on EU enlargement. Countries that haven’t ignored it have moved faster towards the EU. Those who undervalued it have been left on a long and tedious path [towards gaining entry],” Tuzhanskii wrote in a report earlier this year, which was published by the political think tank GLOBSEC.

Transcarpathian Oblast is the westernmost province in Ukraine, as well as the safest. Since the beginning of the invasion in February of 2022, the region has only been hit by one Russian missile. In the provincial capital of Uzhhorod, there is no curfew and the economy is progressing at a good pace. According to data from Ukraine’s Ministry of Economy, of the 1,000 companies that have moved from the provinces near the frontlines to the west, 200 have gone to Transcarpathian Oblast. The provincial government, however, says the number is closer to 400, while the population has grown from 1.2 million before the war to 1.6 million. It’s the closest thing there is to a prosperous Ukraine away from armed violence.

The province borders four countries — Romania, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary — and is home to a dozen national groups. The main ones are the Carpathian Ukrainians, the Hungarians and the Romanians. According to data provided by Roman Moldavchuk — director of the Department of Strategic Communication for Nationalities and Religions of the Transcarpathians — the Hungarian minority is made up of about 120,000 people, or 10% of the total population, while the Romanian minority consists of about 40,000 people.

This province is symbolic of the complexity of Central European identity, as well as of how the political map changes according to the arbitrariness of history. The region was part of “Greater Hungary” for nine centuries, until World War I ended the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And, for a brief time — until the end of World War II — it was actually part of Czechoslovakia. After the war, the Soviet Union forced the incorporation of Transcarpathia into its domains, before it became part of modern-day Ukraine.

Andrjez Sadecki is director of the Central European Department at the Center for Eastern Studies, an academic institution based in Warsaw, Poland. In a telephone interview with EL PAÍS, he highlights that both Romania and Poland are somewhat “dissatisfied” regarding the rights of minorities in Ukraine, but not at the same level as Hungary. “The question of the Hungarian minority has greater weight than in the Polish case, because the Hungarian trauma — [the loss of] two-thirds of its national territory in World War I — hasn’t been overcome. And the Hungarian problem is real and has a European dimension, because it can veto the start of Ukraine’s accession negotiations to the EU.”

The list of grievances presented by the Orbán administration is recurrent. However, the tone has risen with Ukrainian hopes of joining the EU, as well as with demands from Brussels that Kyiv comply with an improvement in the recognition of the plurality of identities that exist within the country.

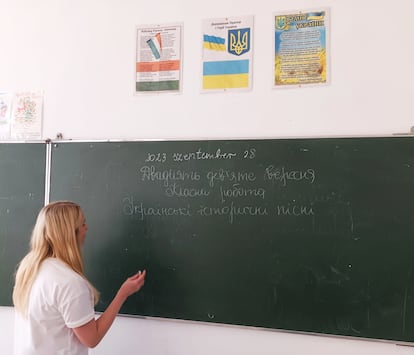

The main Hungarian protest had to do with an education law that was brought in by the Ukrainian government in 2017, which imposes Ukraine as the principal language in the national educational system. Until now, the hundred Hungarian minority schools could teach all their subjects in Hungarian, except for the Ukrainian language. For Budapest — and for the majority of Hungarians interviewed by EL PAÍS in Transcarpathian Oblast — the legal change is an attempt to eliminate Hungarian identity. This past September, pressure from Budapest forced the Parliament of Ukraine to delay the implementation of the law until September 2024.

Julia – a teacher at the Általános Secondary School in Badalovo, where some 80 students study – indicates that they give about six hours of Ukrainian language classes each week. Certain subjects – such as Technology – are also taught in Ukrainian. The government, she confirms, wants Ukrainian to be the dominant language, meaning that it would have to be used to teach major subjects, such as mathematics. “I think it’s normal,” she shrugs. “We’re in Ukraine and there are many people in these towns who don’t speak Ukrainian.” However, her opinion is a minority one in this environment.

“This isn’t a political decision — it’s a social measure, so that these children can have the best educational opportunities in all Ukrainian universities, the best job options, as well as [the ability] to work in the public administration,” explains Moldavchuk, from the provincial government. “There are two issues here,” emphasizes the head of minority policy: “the rhetoric of the Hungarian government and the reality of minorities.” Moldavchuk reveals a recent conversation between President Volodymyr Zelensky and representatives of one of the two political parties that represent the Hungarian minority. Zelensky asked if they had any demands, anything that they thought needed to be improved. “The answer was that they don’t need anything.”

The Venice Commission — a body of the Council of Europe, which is providing Ukraine with recommendations for the reforms it needs to implement if it wishes to join the EU — issued a report this past June, with eight suggestions for Kyiv to improve the recognition of its national minorities. These include the request that official state documents be published in minority languages, that the introduction of Ukrainian as a principal language in schools be delayed for an even longer period, that interpreter services be available for minority languages at Ukrainian public events (in case any attendee is in need) and that quotas on Ukrainian-language content be withdrawn for minority media outlets.

Limiting the Russian language

Radio Pulzus has its studios in Berehove, near the main temple of the Evangelical Reformed Church, which is the second-largest religious institution for Ukrainians of Hungarian descent (after the Catholic Church). The Reformed Church founded Radio Pulzus in 2012. It’s now collectively owned by its community of faithful, as explained by the director, Miklós Barta. It’s the only station for the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. There’s also only one television channel, which broadcasts over the internet: 21 TV. Barta emphasizes that it’s always been a priority for Radio Pulzus to broadcast part of its programming in Ukrainian, even when there was no obligation to do so. Barta estimates that half of Ukraine’s Hungarians don’t speak the official language.

“The legal obligation to use Ukrainian begins in 2016. Currently, only 10% of content can be broadcast in the language of the national minority, but we’re allowed 40%.” Why the exception? Barta doesn’t know how to specify which rule allows it, but he points out that curtailing Hungarian isn’t the objective of the regulations that limit the use of language other than Ukrainian. Rather, the objective of the legislation is to limit the Russian language.

Since the Maidan Revolution in 2014 — which ousted pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych from power — Ukraine has accelerated measures to “de-Russify” the country. With the Russian invasion that began in 2022, the Russian language has practically disappeared from the media. The main concern of the Council of Europe is regarding the rights of the Russian minority in Ukraine… a group that’s difficult to classify, because — especially in the east of the country — it could be almost half of the population.

Moldavchuk confirms that the root problem is Russian and that the measures have been taken to reverse Yanukovych’s proposal to recognize minority languages as official languages. “Yanukovych wanted Russian to be an official language. He disguised it with others, such as Hungarian.” Prime Minister Orbán, meanwhile, is demanding that the Hungarian language receive co-official status from Kyiv, according to the representative of the Transcarpathian regional government. In Moldavchuk’s opinion, the local minority population isn’t requesting this.

Divisions between Hungarians

Barta is in favor of increasing Ukrainian language education, but he also wants to be able to broadcast more in Hungarian from his radio station. Regarding the language and status of the Hungarian population in Ukraine, the director of Radio Pulzus admits that, in his community, it’s normal for there to be differences of opinion.

“We Hungarians are divided between those who watch Hungarian television and are [brainwashed] by Orbán… and those who are patriots, like me.” These are the words of Ybolia, a retiree from Berehove. Ybolia — who prefers not to give her last name — chats in the market with three vendors selling dairy products, all of them Hungarian as well. None of them know how to speak Ukrainian. “It’s not that they’re pro-Russian — it’s just that they’re not Ukrainian patriots,” he clarifies.

Vivien Mitrovka, 18, is a waitress in Uzhhorod, the capital of the region. Her parents are part of the Hungarian minority, but they’ve stopped speaking to their relatives in Hungary. “My family in Hungary supports Russia… and if they don’t support [Russia], maybe they’re neutral.” Mitrovka doesn’t doubt that her future is in Ukraine, which is why she studies Ukrainian philology.

In the Badalovo pub, there’s a small argument among the socializers. Jakob Bulo — an electrician — affirms that Orbán is better than a saint. “Orbán just spouts shit, we’re in Ukraine, we’re Ukrainians,” a neighbor scoffs. He doesn’t want to identify himself because, in the town, he admits, he could have problems. “I’m a Ukrainian citizen, but my nation is Hungary — this feeling will never change,” Bulo responds. He proudly explains that he has a Hungarian passport — another reason for bilateral conflict. Ukraine rejects a dual nationality treaty with Hungary, but Budapest — ignoring this — has issued thousands of passports to Ukrainian citizens. Kyiv doesn’t recognize their validity, but Bulo doesn’t care. “My son has a Hungarian passport and is a full citizen of Hungary. He’s there so that he doesn’t have to go to war.” Ukrainian men of legal age — from 18 up to the age of 65 — cannot leave the country, as they may be called up to serve in the army.

The “ethnic trap” that Kyiv must avoid — according to Tuzhanskii — is the division between Ukrainian groups. Ana Ferencik presents herself as an “authentic Ukrainian of Transcarpathian [Oblast].” She speaks a dialect that mixes several languages, particularly Ukrainian. Ukrainian nationalism — since its first attempt at independence after World War I — occurred in the western provinces of Ukraine, such as Transcarpathian Oblast. Ferencik considers herself the heir to this tradition.

In the Museum of Folk Architecture and Life — an open-air museum located in Uzhhorod — you can see examples of Hungarian culture on display. Ferencik has a strong opinion on the matter. “Orbán has been buying the Hungarian minority with money for five years so that they can grow their businesses and build [properties].” Tuzhanskii — in his GLOBSEC report — estimates that, before the war, the Hungarian government provided annual financing to educational, cultural and business projects among the Hungarian minority in Ukraine, to the tune of $275 million.

Ferencik assures EL PAÍS that all the peoples of the Transcarpathian region “are loyal to the country,” although she acknowledges that many are also loyal to Orbán. But she immediately rails against what she considers to be the common enemy, the true identity problem: the Ukrainians of Russian origin, the refugees from the Donbas region: “Those who have come from the east are the only ones I clearly see [as having] a bad attitude. They hate us because they’re pro-Russian. These Russians are coming here, but we won’t allow them to do what they have done in Donbas.”

In the opposite position to Ferencik is Choboya — the retired history teacher from Berehove. Choboya accompanies this newspaper on a visit to the Ferenc Rakoci II School, the only center of higher education for the Hungarian minority. “Do you know how much money the Ukrainian government invests in our university? Zero,” Choboya sighs. “The Hungarian government finances it, because if it didn’t, [the college] would disappear,”

“For [Ukrainians], the problem is that Hungary helps us… but they forget that they also help thousands of Ukrainian refugees.” Choboya confirms that his two sons — both with Hungarian passports — reside in what he considers to be his motherland, in order to avoid being called up.

Sadecki, at the Center of Eastern Studies, believes that Budapest’s complaints — while exaggerated — are justified. Yet, he believes that Orbán’s proximity to Moscow plays against the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. “There will always be some pretext in Hungary to protest,” the academic warns, “because the threat of vetoing Ukraine’s access to the EU and NATO is a weapon to negotiate its interests in Europe.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.