The Venezuelan ambassador in London invoiced $9 million to the network that looted PDVSA, her country’s oil company

A company controlled by Rocío del Valle Maneiro signed a contract worth more than $14 million with a group of Venezuelan politicians, who are being investigated for corruption. The plot also had a former senior security official from Caracas on the payroll: it paid him $1.6 million

A Panamanian company controlled by Rocío del Valle Maneiro – Venezuela’s ambassador to the United Kingdom — signed a contract in 2012 to supposedly provide advisory services. In actuality, it collected more than $14 million, as part of a plot orchestrated by former Chavista vice ministers, who are being investigated for looting more than $2 billion from the state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S. A. (PDVSA). This is according to a confidential report from the Financial Intelligence Unit of Andorra, which EL PAÍS has had access to.

When she signed the agreement, the diplomat was the head of the Venezuelan diplomatic delegation in China, a position that she held between 2004 and 2013.

About 30 members of the criminal network have been prosecuted in Andorra, where they hid their loot, thanks to the protective cloak of banking secrecy, which was in force until 2017. These former Venezuelan officials collected bribes from foreign companies — mainly Chinese firms — which later obtained multi-million-dollar awards from the state-owned oil company. The looters operated between 2007 and 2012.

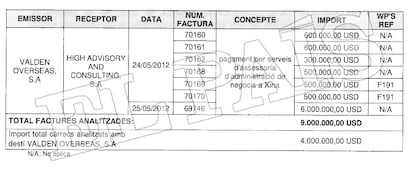

The Panamanian firm (with no registered activity) — Valden Overseas S. A. — was the vehicle used by the diplomat to sign the agreement. 100% of the firm’s capital is controlled by her son, Juan Páez Maneiro. The ambassador was hired by another Panamanian company — High Advisory and Consulting S. A. — led by the businessman and leading member of the corrupt organization, Luis Mariano Rodríguez Cabello. The contract was valid for two years.

While it’s unknown how much Del Valle Maneiro earned for her alleged advisory services, the documents reveal that the Panamanian company linked to the diplomat issued seven invoices in two days in May of 2012, for a total of $9 million. All of this was issued to the PDVSA plunderers’ frontman. “Payment for business management advisory services in China” is the note listed in the invoices.

Researchers at the Financial Intelligence Unit of Andorra (UIFAND) — a public organization in the Pyrenean country that fights against money laundering and is investigating the actions of those who looted PDVSA — have raised questions in a confidential report, dated from November of 2022, regarding the veracity of the work that Del Valle Maneiro performed for the network. They have connected the invoices with a corrupt mechanism: “[The contract] does not specify the modalities and conditions of the advisory services to be provided,” the agents emphasize. They call the agreement “ambiguous and imprecise.”

UIFAND also maintains that Del Valle Maneiro — as revealed by this newspaper — managed four accounts in the Banca Privada d’Andorra (BPA), which contained $4 million. To mask the trail of the funds under suspicion, she resorted to a constellation of Panamanian firms created ad hoc by the bank. In this maneuver, in 2013, the ambassador transferred $1.7 million to accounts in Switzerland and Miami in the name of one of her sons, according to investigators.

The diplomat’s lawyer in Andorra — Jordi Segura — denies the irregular origin of the funds that Del Valle Maneiro deposited in the BPA.

Like her lawyer, the ambassador has always defended the legality of her actions. When she testified as a defendant before a court in Andorra, in September of 2018, she justified that the money she deposited into the BPA came from a sale made in 2011 of her inheritance rights – where she was among 14 beneficiaries – to a 19,000-hectare plot of land that her family owned in the Venezuelan state of Sucre.

The ambassador alleges that she collected $5 million after the transaction and that the buyer was Diego Salazar – member of the network and cousin of Rafael Ramírez, the former Chavista Minister of Energy, former president of PDVSA and former ambassador to the UN.

“I have never been part of a corporation or company of any kind. This clashes with the functions that I have had all my life, 38 years of service. I am a career civil servant, I have a bachelor’s degree, a master’s degree and a doctorate… I have never acted as an intermediary or assistant, nor as anything [related to] Diego Salazar, in any company or government... I have committed the sin of being a lifelong friend of Diego’s family and of having sold him my inheritance rights,” she defended herself five years ago before a judge.

When asked if she knew Rodríguez Cabello, the ambassador responded in the affirmative. She pointed out that the alleged frontman of the network that moved $1.2 billion through 11 BPA accounts “was part of Diego [Salazar]’s team.” He personally took $154 million in contracts from Chinese companies.

Andorran investigators connect Del Valle Maneiro’s income with an agreement worth $20 billion — signed in 2010 between Venezuela and China — that allowed companies from the Asian giant to obtain contracts from the Latin American country. The group allegedly took advantage of the initiative to make businessmen —who were seeking contracts with PDVSA— hand over cash bribes.

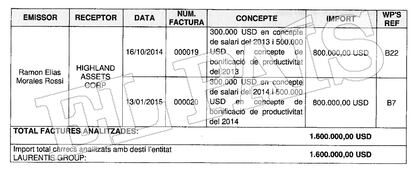

The Venezuelan ambassador to the United Kingdom was not the only official from the Latin American country paid by the corrupt organization. Ramón Elías Morales Rossi —the former secretary of Citizen Security in Caracas— collected a total of $1.6 million between 2014 and 2015 from the criminal network, according to documents that EL PAÍS has had access to.

Through the financial instrument Laurentis Group Inc, the former senior Caracas official signed a contract with Rodríguez Cabello, the frontman of the plot. In force between 2011 and 2019, the agreement stated that Morales Rossi would receive $300,000 annually during this period. It also enabled her to earn up to another half-a-million dollars annually in dividends.

The former secretary of citizen security in Caracas issued two invoices between 2014 and 2015 for a total of $1.6 million to the network, with notes detailing the payments as being for a “2013 salary” or “productivity bonuses.”

To justify his income, Morales Rossi told the BPA that the money was remuneration for his work as a consultant for the firm Inverdt Business Advisors CA. Behind this company was the Caracas engineer José Enrique Luongo Rotundo, who is being prosecuted in Andorra for belonging to the criminal network.

Andorran investigators, once again, are questioning the veracity of the contract presented by the former senior official. They maintain that there is no evidence to prove the veracity of his alleged work. “There is no signed document identifying the projects or services provided by Morales Rossi,” the UIFAND agents point out.

EL PAÍS has attempted —without success— to obtain Ramón Elías Morales Rossi’s version of the events that have transpired.

Formed by over 30 former officials of the powerful state firm —including several loyalists of deceased former President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013), such as Nervis Villalobos and Javier Alvarado, his former vice-ministers of Energy— the network that looted PDVSA devised an elaborate scheme through which it received under-the-table commissions of up to 10% from businessmen. The firms that paid the bribes —especially Chinese companies— were later awarded energy contracts.

To mask the trace of the money, the organization hid its loot through an opaque web of accounts in the BPA, more than 4,000 miles away from Caracas. The flow of funds circulated through 30 companies, which were registered in Switzerland and Belize.

In order not to raise suspicions, the income was camouflaged under the umbrella of consulting jobs that —according to investigators— didn’t exist. The Andorran judiciary accuses the members of the organization of money-laundering in a banking establishment. Meanwhile, the BPA —the financial entity in the small Pyrenean country that hosted the flow of dirty money— was raided in 2015 by the Andoraan authorities, for allegedly engaging in money-laundering activities for criminal groups.

The ambassador’s lawyer: “Del Valle Maneiro has proven the origin of the funds”

Jordi Segura – the lawyer in Andorra for the Venezuelan ambassador to the UK, Rocío del Valle Maneiro – assures EL PAÍS that his client has justified the origin of the $4 million that she deposited in the Pyrenean principality. “Its origin was documented, which has absolutely nothing to do with the [allegations] in your message,” the lawyer responded, when asked about the latest report from the Financial Intelligence Unit of Andorra (UIFAND), which connects the diplomat’s money with the plot that looted PDVSA.

According to Segura, Del Valle Maneiro hasn’t been prosecuted in the so-called Venezuela case, which concerns the alleged theft of $2 billion from the public energy company between 2007 and 2012, as well as its concealment through the Banca Privada d’Andorra (BPA). The lawyer maintains that – following her statement in an Andorran court in September of 2018 – the diplomat’s procedural status hasn’t changed. “Mrs. Maneiro hasn’t been prosecuted in said case, nor has she subsequently been required to give another statement, or participate in any proceedings of any nature,” he clarifies. “Currently, Mrs. Del Valle Maneiro’s situation is exactly the same [as in 2018],” he emphasizes.

Segura denies that his client has been judicially questioned about the multi-million-dollar contract she signed with the network of looters. “At no time was Del Valle Maneiro asked about these aspects and she answered all the questions [in her 2018 judicial statement] with precision and clarity.”

The ambassador’s lawyer also dismisses the confidential UIFAND report from last November, which connects Del Valle Maneiro with a contract that allowed her to collect up to $15 million from the criminal network when the diplomat was Venezuela’s ambassador to China. “It’s only a declaration of suspicion by the UIFAND – not any decision or jurisdictional act. What matters is what the judge says, not what the UIFAND says. There’s no judicial investigation [just because] the UIFAND declares something to be suspicious,” Segura concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.