The golden honey from Colombia that saves lives

In the biodiverse region of Guainía, a chemist, a zootechnician and a biologist convinced indigenous communities to replace coca crops with beehives

Throughout our lives, we all inevitably encounter moments that we want to do over again. For Fabio Pérez, this happened in Venezuela, right on the border with Colombia. Pérez is in charge of producing some of the finest honey in the world made by tiny, stingless bees no larger than a quarter inch.

Before telling us about his biggest failure, Pérez, a tough-looking guy with a reassuring smile, looks at the surrounding indigenous community of La Ceiba near Puerto Inírida, the capital of Guainía department in eastern Colombia. To get here, we took an hour-long flight from Bogotá, and then a 45-minute boat ride along the Inírida River.

Under the shade of linden trees and magnolias are 195 wooden boxes measuring 10 x 10 inches (25 x 25 centimeters) painted green and blue. There’s a treasure inside, in this part of the Amazon jungle that just a few years ago was covered with coca bushes, the leaf that turned Colombia into the world’s biggest cocaine producer. Fabio delicately takes a lid off one of the boxes to show us bees doing what they have been doing since the species first appeared in the Lower Cretaceous period 145 million years ago when the continents separated. Thousands of bees are inside, transforming nectar collected from flowers and storing it as a golden, fruity smelling honey in perfectly structured hexagonal hives. And of course, they also play a crucial role in pollination.

“We depend on them to live,” said Pérez, “and yet we spray them with pesticides, burn them, and destroy their nests when we deforest jungles for cattle ranching and agriculture. They’re the most important living things on the planet, and 70% of the world’s agriculture depends on 20,000 bee species. Without pollination, the plants that millions of animals feed on could not propagate. Without bees, wildlife would quickly disappear.”

How does he know all this? Fabio Pérez comes from Guainía, an area with one of the highest poverty rates in Colombia, almost four times the national average. It’s the fifth largest department in Colombia (almost twice the size of Switzerland) and the least densely populated with only 53,000 inhabitants (70% indigenous), most of whom don’t attend school past the fifth grade. They make a living from fishing, occasional handicraft sales, illegal mining and coca cultivation.

In 2007, Alexandra Torres, a chemistry professor at the University of Pamplona (Spain), and her husband, German zootechnician Wolfgang Hoffman, a bee specialist, came to La Ceiba with Colombian biologist Fernando Carrillo, the director of the Aroma Verde Foundation for ecotourism. They had an idea, a sustainable development project that meant teaching indigenous people to raise bees. It would be profitable, since they could sell their honey to visiting tourists, and also good for the world. Fifty hives can pollinate 123 acres (1,256 hectares) of forest.

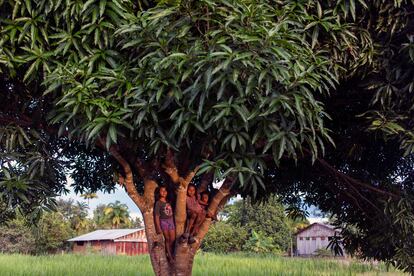

With $40,000 in funding from Swiss company Ricola, the three scientists spent four years teaching the people of La Ceiba how to extract beehives from tree trunks. They then transferred them into small wooden boxes to multiply. The outcome was stunning. As each individual bee gradually pollinated 2,150 linear yards (2,000 linear meters) of forest, mango, açai and arazá trees began to flourish throughout La Ceiba. They used small syringes to extract the honey and fill jars that were shipped out on planes. Tourists dubbed it the Honey Route, and flocked to the area to buy up all the honey.

“It’s a project that creates opportunities and promotes sustainability,” said Carrillo, who followed his heart and came to live in Guainía with his wife and two children “Tourism has been the driving force behind a project like the bees.” Every time a tourist travels with the Aroma Verde Foundation, six dollars of their total purchase goes to support the bee project.

That’s why Fabio Pérez no longer worries about coca cultivation. He works with seven species of stingless bees, out of the 120 that exist in Colombia. Aware that 30% of Melipona bees have disappeared around the world, 34 local indigenous families formed an association led by Pérez that produces over 1,153 jars of honey a year. Their success interested other communities like Morroco near La Ceiba, which established 47 box hives with the association’s help.

“The bees saved me,” said Pérez. “I am indigenous and supposedly know all about nature and how to protect it. How wrong I was. My biggest failure was to destroy my environment, but the bees healed my soul.” It happened in Venezuela’s Yarama National Park where he worked as a miner in 2004. He was told that to get enough gold for one ring, he had to dig up 20 tons of rock and soil. “So I destroyed acres of pristine forest.”

Deforestation led to the disappearance of a once vibrant stream where Pérez bathed and fished. He saw how a dense forest transformed into a desert of drifting white sand. He felt the emotional impact of chopping down a tree and seeing four delicate toucans fly out and leave their eggs behind. “I can’t believe I used to be that person,” he lamented.

How did bees conquer greed and transform people?

Colombia comes second in terms of biodiversity, right after Brazil. Guainía, which means “land of many waters” in the Yuri language, is a true gem. Near La Ceiba is one of the world’s largest freshwater wetlands known as the Eastern Fluvial Star, formed by the convergence of the Inírida, Guaviare and Atabapo rivers. In 2014, UNESCO recognized its diverse waterfowl habitat.

“The Atabapo [River] is particularly delightful,” wrote German scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, who came here in 1800 to observe how these three rivers flowed into the Orinoco River, the third largest in terms of water flow rate after the Amazon and the Congo rivers. Humboldt called this area the eighth wonder of the world, where rainbows dance in a game of hide and seek, leaves unfold to greet the rising sun, and flowers twirl in the flickering light.

This area of Colombia is part of the Guiana Shield, one of the oldest geological formations on Earth. It features high hills and plateaus known as tepuis, with steep vertical slopes. The Mavecuri, Mono and Pajarito hills that jut upwards from the banks of the Inirida River were immortalized in Embrace of the Serpent (2015), the first Colombian film to be nominated for an Oscar.

The number of tourists traveling with Aroma Verde has quadrupled. In 2019, the area welcomed 400 visitors, and by 2022, that number had surged to 1,800. “Here, I can’t help but realize how incredibly tiny I am in this vast universe. I feel humbled and grateful,” said a 28-year-old tourist who makes a living as a disc jockey. “I totally forgot how amazing it feels to just sit back and quietly watch the sunset,” said another tourist. Guainía is an ancient and serene world, untouched and innocent. The granite mountains boast white flowers with a sacred aroma, while the murmuring rivers offer solace to troubled souls. In Guainía, one can live peacefully, free from anger. Even the bees contribute their wisdom to this tranquil place.

Tourists discover that everything functions more effectively when people work together. “Each bee is committed to fulfilling their designated role within the hive. Their society functions like a finely tuned clock, maintaining a precise rhythm to accomplish objectives efficiently,” said biologist Rodulfo Ospina, who is in charge of a unique, 40,000 bee collection at Colombia’s National University.

The one weakness of the hive is its own inhabitants. It’s made of wax that will melt when the internal temperature rises above 98.6ºF (37ºC), so the worker bees soak themselves in water to keep the wax cool. “The bees themselves work tirelessly to keep the hive alive,” said Ospina.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.