Petro and the high cost of a false tweet: The Colombian president’s blunders on Twitter

The leader has been criticized for favoring immediacy over caution on the social network, a problem that came to the fore when he wrongly tweeted that four missing children had been found

It’s not as if no one has told Gustavo Petro to tone it down on Twitter, where he can tweet 15 or 16 times in a day, no matter how busy his schedule is. Politicians, academics, experts in political communication, journalists and the public have all called on him to be more prudent about what he posts. Petro has made more than one blunder on the social network. The most recent took place on Wednesday, when he hastily and incorrectly tweeted that four children who have been missing in the Amazon rainforest since May 1 had been found. The government explained on Thursday that the message — which caused great pain for the family — was based on incorrect information provided by Bienestar Familiar (ICBF), the institution in charge of the protection of minors. But Petro posted the news before confirming it with the very authorities that he himself tasked for the rescue. Once again, haste won out over caution.

“I have decided to delete the tweet because the information provided by the ICBF could not be confirmed. I’m sorry about what happened,” he wrote the next day on Twitter. The family of the missing children have called on the media that reported the false news — and on the Colombian president — for restraint.

But Petro is reluctant to change his Twitter behavior. Or, at least, that’s what people close to him have said.

Laura Sarabia, his chief of staff, recently told the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo that she has repeatedly asked the president to show more restraint on Twitter — but to no avail. “The president’s argument is that if he doesn’t do it, no one else will,” she said. Petro knows that the success of his political project depends both on the government’s performance and communication, and does not want to let go of the loudspeaker. Sarabia said that she tried to offer alternatives, such as a spokesperson. But Petro doesn’t believe there is anyone at his level who can speak on his behalf. Interior Minister Luis Fernando Velasco was meant to be his spokesperson, but according to Sarabia he lacks the necessary recognition.

But for a head of state, the cost of managing a Twitter account and succumbing to the fast-moving world of social media can be very high. This was seen on January 1, when the president jeopardized negations with the National Liberation Army (ELN) by incorrectly reporting that the guerilla group had agreed to a ceasefire. There was no such deal, and negotiators were angered by the misinformation.

Petro has also retweeted posts from fake Twitter accounts. Some cases may appear harmless. In 2018, when he was a senator, Petro shared a post celebrating the national quantum physics champion, but mistakenly accompanied the message with a photo of a Spanish porn actor. Other cases appear more opportunistic: this year, to defend his health reform, he shared photos of what he claimed to be a dilapidated Colombian hospital, but the images were actually of a Venezuelan center.

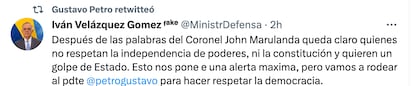

In the last month, Petro has also twice retweeted messages from a parody account of the defense minister. The first announced that the four missing children had been found, and the second called for people to take to the street in support of the president after a former military officer demanded his ouster. The consequences of an incorrect tweet from the defense minister’s parody account become considerably higher if the message is retweeted by the president, who is head of the armed forces.

Petro, like other activists and political leaders on Twitter, believes the social network provides a more direct relationship with the public — precisely because it has no intermediaries: there are no fact-checkers, editors or publicists. “The space for communication resistance on social media has been vital to building the Human Colombia project,” Petro posted on Twitter in 2018, when he was a presidential candidate. Both his supporters and critics agree that since he opened his Twitter account in 2009, he has used it with a skill that few other Colombian politicians have.

As head of state, Petro continues to prefer Twitter to institutional communication channels. Even after promoting a daily government news outlet, diplomatic relations with Peru, Chile and El Salvador have been conducted more through tweets than through the Foreign Ministry. It’s also his favorite place to take on political opponents, even international ones. Petro has found his perfect online nemesis in Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, who enjoys Twitter as much as he does. In March, the two engaged in a days-long spat that began over prison policy and ended with the two labeling each other as corrupt. No one won the argument, but perhaps they each won some followers.

According to the Twiplomacy ranking, Petro was the fourth most-influential world leader on Twitter in 2022, alongside Indian leader Narendra Modi, U.S. President Joe Biden and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. It doesn’t matter that less than 10% of the Colombian population uses Twitter. Given every journalist follows him on Twitter, he is able to set the agenda every day with what he posts or retweets on the network.

Petro agrees with those who argue that Twitter is the most transparent means of communication, believing that traditional media defend the interests of businesspeople and politicians. Colombia’s Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP) — which has criticized Petro for using Twitter to attack journalists — agrees that in some cases, it is positive for the president to enter the public debate. “The head of state’s participation in public debate on social media plays an important role in democracy, as it offers a real-time communication channel with some possibilities for direct interaction with citizens and the media,” states FLIP. With the right strategy, Petro can provide effective communication on healthcare reform, the energy transition and his plans to bring “total peace” to the country.

But FLIP has also criticized Petro for accusing journalists on Twitter, rather than asking a media outlet for a formal rectification. And Twitter also has a darker side. Given it has no editorial controls, it is at risk of disinformation. And due to its format and character limits, it tends to breed confrontation, meaning that debate may be shut down rather than opened.

Anyone who has spent time on Twitter knows it is easy to go from calm to anger, to choose immediacy over caution, to share false information that resonates with one’s own prejudices rather than messages that reveal uncomfortable truths. Fact checking and caution do not get the adrenaline running. In an electoral campaign, where a timely tweet can win over voters, Petro has shown his skill. But as president, showing lack of restraint on Twitter comes with heavy consequences, as happened this week when Petro raised the hopes of a family desperately worried about four missing children, only to explain, hours later, that he had tweeted too soon.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.