Kabul’s only library for women closes due to Taliban threats and harassment

Zan offered books on loan and educational workshops. Co-founder Laila Basim has been targeted by the Afghan regime: ‘Our fight is one of pens against guns’

The United Nations considers that the systematic deprivation of the rights of women and girls imposed by the Taliban in Afghanistan may amount to gender persecution, a crime against humanity. Girls cannot study from the age of 12; women are not allowed to work in government agencies or for non-profit groups and now they have also been banned from entering parks and gardens. They cannot travel anywhere without a close male relative. Afghan women have been left with very few rights and even fewer possibilities to access knowledge.

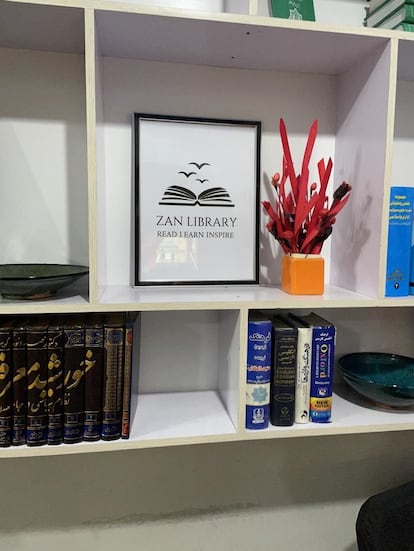

Since mid-March, they have also been deprived of one of the last remaining bastions of culture and freedom in Kabul: Zan Library. Two weeks ago, this center — the only one for women in the city — had to close due to threats and harassment from the Taliban, explains one of its founders, 28-year-old economist Laila Basim, via WhatsApp. When the library disappeared, she says, “a hope ended.”

“[Afghan women] no longer have a place to talk and study,” adds Basim in messages sent from Kabul.

Zan, the name of the library, means “woman” in Dari, the variety of Persian that about 40% of Afghans consider their mother tongue. Opened in August 2022 — coinciding with the first anniversary of the return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan — its goals were to promote culture and reading among women and girls “who have had the doors of schools and universities closed to them,” explains Basim. But frequenting the library also became an act of “civilian resistance by women against the misguided policies of the Taliban.”

Located in a basement of the market in the Red Pol neighborhood of the Afghan capital, the library offered its “more than 400 members,” in an estimate provided by Basim, books on loan in four languages (Persian, Pashto, English and Arabic), as well as free workshops and training sessions on “women’s rights, politics, religion and other topics” twice a week, in order to “increase women’s knowledge.” All of the library’s funds, which Basim estimates at 5,000 volumes, and even the shelves, tables, and chairs were donations. Most of the donors were Afghan women, although there were also a few men as well as some “foreign friends,” says Basim without offering more details.

“In the seven months that the library stayed open, the Taliban sealed the door twice, but we opened it with the help of friends and continued working. But the Taliban did not stop there. They started coming every day and asking us what was going on in there and what the readers were doing in the library. One day, four members of the security forces stormed in and started asking me who had given us permission to open. Then they told us that a woman’s place is in her house and not outside of it,” recalls Basim.

“For 19 months [since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021] my colleagues and I have been fighting against the policies of the Taliban. Ours is a war of pens against guns,” she explains. Basim says that she and the other volunteers at the library have received threats by telephone, and continue to get them even now. The thousands of books that they had collected for months are now stored inside their homes.

At gunpoint

Laila Basim was already in the crosshairs of fundamentalists before she even founded Zan Library. A university graduate with a degree in economics, she’d been working in the Cabinet of the Economy Minister of the previous Afghan government. When the Taliban took Kabul, she, like many other highly qualified Afghans, was expelled from her job. Overnight she found herself unemployed and without an income, just like her husband, a lawyer who is “her main support” in what she calls her “fight.” She was forced to sell her jewelry to get by, but almost immediately, she co-founded an organization of women determined to stand up to the radicals — the Spontaneous Movement of Afghan Women Protesters — another reason why she has drawn the ire of the current regime.

The United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan, Richard Bennett, presented a report in February in which he not only denounced the curtailment of the rights of Afghan women, but also the prohibition to demonstrate and the “excessive use of force,” with beatings and warning shots to disperse demonstrators. The document said that Afghan protesters — “often women” — are subjected to threats, intimidation, arrest and ill-treatment while in the custody of the authorities.

Basim’s account confirms some of these accusations: “In December 2021, we demonstrated in the street and an Iranian television crew interviewed me about the killings in Panshir province [northeast Afghanistan]. After that interview, the Taliban called me and warned me that they would find my house and kill me. In another protest in front of United Nations headquarters in Kabul, a Taliban intelligence officer drew his gun and pointed it at me, telling me that if we didn’t leave in five minutes, he would shoot at me.”

“In these 19 months, I have had to move six times,” she adds. This Afghan woman believes that “creating a library is neither the first nor the only way to fight the Taliban and their misogynistic ideology. For us, there is no other way, we have to keep fighting. As long as we are alive, we will continue fighting for our rights and for equality.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.