Gustavo Petro: The ex-guerrilla who could become Colombia’s next president

From his militancy in M-19, where he named himself after a character in ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude,’ to his exile in Belgium, the 62-year-old’s journey to this point has been something of an odyssey. Will he be able to defeat Rodolfo Hernández at Sunday’s election?

It’s hard to know what Gustavo Petro is thinking just by looking at him. Mysterious and solemn, the Colombian presidential candidate has a faraway look in his eyes, as if his mind were in several places at once. Not even his advisors always know what to expect from him. A few weeks ago, one of them tried to convince him to soften his stance on an issue that had made him unpopular with some voters. The candidate looked over his papers and responded: “My positions aren’t negotiable. I’m not going to back down.” Then he sat back to observe the sky from the airplane’s window.

Petro is stubborn, says his daughter Sofía, but she believes he’s where he is today thanks to this stubborn streak – on the brink of becoming the first leftist president in Colombia’s history when the country heads to the polls on Sunday. This is the third time Petro has run for president. As an ex-guerrilla fighter, who is feared by the upper class and business elite, Petro seems an unlikely candidate. But in the past few years, he’s distanced himself from Cuba and Venezuela, become more involved with the feminist movement, and is now talking about forming a progressive alliance with Chilean President Gabriel Boric and Lula de Silva, who is running for president in Brazil. He’s also stopped dressing like a social leader in a bid to appear more like a statesman.

Despite his shyness, Petro is a powerful public speaker. After holding 100 rallies, the 62-year-old believed he could win the elections in the first round by securing at least 50% of the vote. But that didn’t happen. In the runoff, he is up against the populist businessman Rodolfo Hernández, who has been using social media to show that he is in touch with the everyday people – something that does not come across when he takes to the stage.

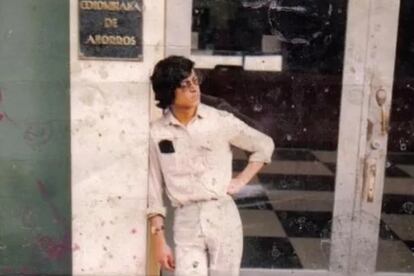

Petro’s journey to this point has been something of an odyssey. Many people would have given up somewhere along the way. Petro was born in the Caribbean town of Ciénaga de Oro, but his parents moved to Bogotá, the capital, when he was still a baby. He studied at a school in the village of Zipaquirá, where writer Gabriel García Márquez was also a student. At age 17, he joined M-19, a guerrilla organization that aimed to open up democracy in Colombia, and assumed the nom de guerre “Aureliano” after a character in García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. The armed group had recruited Petro for his intellect – back then, he was a scrawny youngster and suffered from bad myopia.

It was during this period that Petro became a social leader. Together with hundreds of families, he helped take over a few parcels of land, which were used to create a new neighborhood, Bolívar 83. “I will never forget those days, because they linked me forever to the world of the poor,” Petro writes in his autobiography. Petro was briefly on the council of Bolívar 83, before being captured and tortured by the military in 1985. Since that moment, he has been dogged by the premonition that his way of rebelling against the world would lead him to a violent death.

After leaving prison, he tried but failed to create an armed group in the mountains – being a guerilla was not his strong suit. In those years, he cut off all contact with his family and friends. He reintegrated into civilian life in 1990, when M-19 signed a peace treaty with the government. The last head of M-19, Carlos Pizarro, was assassinated a month and a half later while running for president. His daughter, María José, who is now a lawmaker in Petro’s coalition, says: “Gustavo is much more rational [than Pizarro], he’s a man of proposals built on the maturity [he has learned] in all these years.” She believes that his experience in M-19, surrounded by idealist ideas, has made him something of a savior.“Everyone in that generation of men and women is pretty messianic. What makes Gustavo lucky is that he’s survived.”

Petro was first elected to Congress in 1991, but after finishing his term, he sought asylum in Belgium – former guerrilla fighters who were entering politics in Colombia were being assassinated. In Europe, he became an environmentalist, something which is seen in his proposed policies for Colombia. Petro wants to suspend oil exploration and promote a green energy transition. Indeed he believes that all of Latin America must change its economic model; focusing less on extractivism and more on production, industrialization and knowledge. Returning to Colombia in 1998, he was elected again to Congress, becoming one of the more admired lawmakers of the opposition party. The biggest stain on his legislative career was supporting Alejandro Ordóñez, a polarizing ultraconservative figure close to former president Álvaro Uribe, as attorney general.

As a lawmaker, he was a harsh critic of President Uribe (2002-2010). He spoke out against the links between politicians and paramilitaries, and the spying campaigns of the secret service, of which he himself was a victim. Petro believed that with this good reputation, he might reach the presidency. He ran in 2010, but did not have much success. But he didn’t give up. He became the mayor of Bogotá. There is no consensus on whether he did a good or bad job. He was able to achieve the lowest homicide levels in 20 years; he extended the school day for public high schools and he launched a policy that guaranteed a minimum amount of water for the poorest households. Many old staffers agree that it is difficult to work with him, as the frequent changes in his unstable government demonstrated. He was fired by the attorney general, Ordóñez, for trying to deprivatize the city’s trash collection service. In response, he called a protest, which brought out huge crowds to Bogotá's City Hall. It was the beginning of Petrismo.

In 2018, he ran for president again. But the country had just voted against the peace agreement with FARC and was not ready to support a former guerilla. But again he didn’t give up. Petro has been campaigning ever since. And now it seems as though the conditions are in his favor. With running mate Francia Márquez, he won the first round, defeating Federico “Fico” Gutiérrez, the right-wing establishment candidate. But now he must overcome a different sort of rival: Hernández, an anti-establishment businessman who represents the public’s disillusionment with politicians – politicians like Petro. To win the presidency, he must defeat this final challenge. But will Aureliano the idealist, the fiery lawmaker, the combative mayor and the stubborn candidate, be up to the task?

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.