The lost architectural gems of Spain’s recent history

A look at the landmark buildings that served as food markets, factories and movie theaters and that have been demolished through ignorance or speculative greed

In Spain, a multitude of unique buildings of great architectural value have met the same tragic end: demolition. This has variously been due to land speculation, political motives, or because the building in question was conceived as a temporary structure; but whatever the reason for razing them, these architectural landmarks – now no more than a memory in the popular imagination – demand that their story be told and their legacy appreciated.

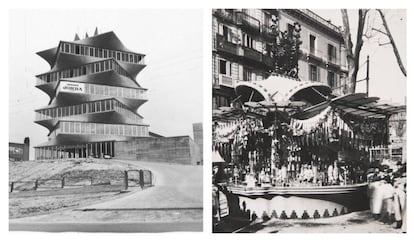

1. Canaletas Kiosk, Barcelona

Antoni Rovira i Trias’ original building was just a small wooden structure that sold refreshments, coffee and water. Built in 1877, it was located on the upper stretch of the Rambla avenue, near the fountain of Canaletas, and it was part of a series of projects entrusted to the head of Barcelona’s Buildings and Ornamentation Department to boost the development of the urban landscape and bring it in line with other European cities.

The kiosk’s first owner was Felix Pons, who had a refreshment stand near the Boquería market, further down the Rambla. But in 1901 it was taken over by Esteve Sala I Canyadell, who had a bar near the Barcelona FC soccer grounds. The kiosk prospered from 1901 to 1916 after Esteve noticed that soccer fans walking out after a game often gathered at the Canaletas section of the Rambla to discuss the match. To take advantage of this, he established communication with the bar to learn how Barça had played, and prepare his kiosk with extra food and drinks according to the mood.

Structurally, Esteve arranged for a series of extensions and redesigns to cater to his growing clientele. These included a project by architect Antonio Utrillo, who added a modernist twist that turned the kiosk into a city icon. Esteve began organizing debates at his kiosk and eventually his links with Barça were such that he became the club’s manager between 1931 and 1936.

The kiosk was torn down in 1951 on the orders of Mayor Antonio María Serrano. Some point to Esteve’s strong ties with Barça, and thus with Catalan nationalism, as the reasons behind the move, although the official line was that the authorities wanted to make the Rambla more attractive to pedestrians.

2. The Eucharistic Congress Altar, Barcelona

The 35th Eucharistic Congress was celebrated in Barcelona in the spring of 1952. It was the first to be held after the Second World War – the previous one had been in 1938 in Budapest amidst rising pre-war tensions. The 1952 congress was Franco’s first international event and it was publicized with the slogan “The Eucharist and Peace.”

The altar was designed by Josep Maria Soteras in collaboration with fellow architects Vilaseca and Riudor and set up on Diagonal avenue – then known as Generalísimo avenue. It was meant to be a temporary structure, but due to its unique design, it became something of an icon that should have been preserved.

The construction addressed two needs: one spiritual and the other practical regarding the distribution of facilities and space. The solution was a huge circle representing the sacrament of the Eucharist, with a canopy 25 meters in diameter held up by three supports: a 35-meter high cross and two braces representing faith, hope and charity in a bid to accentuate its spirituality.

These features used a pentagonal base rising five meters above street level, which could be entered from the back under the cross located in the last apex of the pentagon. The entrance led into the vestry as well as the area reserved for radio broadcasting, toilets, telephone booths, a storage room and an area for security forces and firefighters, all of which was hidden below the shadow of the canopy. The canopy, which resembled a vault, had a circular window that let natural light through during the day and artificial light by night.

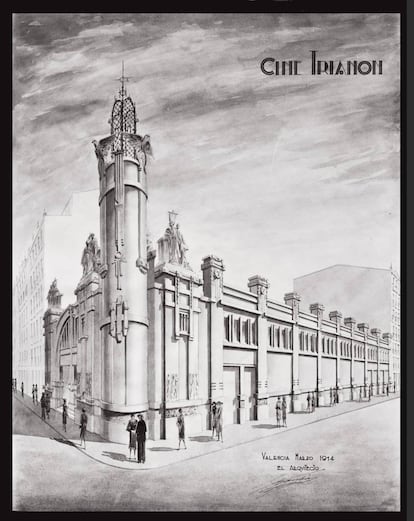

3. Trianón Palace, Valencia

This project was sponsored by the businessman Manuel Porres and designed by the young architect Francisco Javier Goerlich, 28, and rapidly made headlines due to its grand pretensions. Large enough to fit 1,500 people, it was built in a record seven months and inaugurated in 1914 on Pi y Margall street, which has since been renamed Paseo de Ruzafa.

Goerlich wanted the construction to be modernist in style and he decorated the façade with various sculptures. Within, the architect Luis Benlliure designed a hall in the style of Louis XIV with an imposing central staircase that led to the orchestra section and two side staircases going up to the first floor.

It was originally conceived as an auditorium offering plays and concerts, but some years later, due to financial difficulties, it was renamed Lírico Theater and used exclusively as a movie theater, making it the first Spanish cinema on that scale. It closed, however, in 1948 and there was no legislation in place to prevent it from being torn down.

4. Hispania pencil factory, Ferrol

This project was the brainchild of a stationery salesman who had become aware of the profits to be made from making writing materials. It was 1934 and, with the help of a group of partners who all lived in Ferrol, in the northwestern region of Galicia, he set up a pencil factory that he called Hispania S.L. using existing infrastructure within the city. Due to the company’s success, however, a bespoke factory was built in 1938, which was designed by Nemesio López Rodríguez using simple straight lines in the style of industrial rationalism, popular at the time. It also included touches of art déco, a style that had previously been used in Spain.

The factory started out with pencils and fountain pens but it also produced colored pencils, wax crayons and felt tip pens. During the 1950s, it was producing 50 million units a year and employing a staff of more than 400. But in the 1960s, the Spanish economy was in a critical situation following a prolonged period of autarchy, during which Franco had sought economic self-sufficiency. The regime adopted a number of austerity measures combined with some liberalizing policies that dealt a blow to certain industries, which now found themselves unable to compete on the international market.

After accepting that it could not win back the market share lost to China, Taiwan and Czechoslovakia, the company made a plan to wind up its business when its staff retired, with a date set for October 30, 1986. The factory was sold and the building was left empty, with a view to using the land for property development, despite a strong lobby arguing for it to be turned over to public use. It was eventually torn down in 2012.

5. The s.e.i.d.a. garage, Madrid

This building should have been preserved at all costs, not just because of its appearance but also because of its purpose, which reflected a more leisurely age. Designed by the architect José de Azpiroz y Azpiroz in 1930, it featured rationalist lines that were softened at the building’s corners while the horizontal nature of its structure, which occupied almost an entire block, was emphasized by a thin white cornice that split the entrance.

The fact that it was low and gave onto two streets – Espronceda and Fernández de la Hoz – allowed the sidewalks to be bathed in plenty of natural light, but it is the building’s use, rather than its design, that triggers nostalgia. Here, cars were pampered in a building so spacious that it housed a workshop, an administration area, a salesroom selling both new and second-hand vehicles, a gas station and a vast waiting area complete with a bar.

The gas station was located in the chamfer, which was decorated with a winged pilaster – the company logo. Unfortunately, such a rambling structure was inevitably going to fall prey to speculators in a neighborhood like Chamberí, where space is at a premium.

6. Olavide Market, Madrid

Olavide Market is possibly the starkest example of the loss of national architectural gems. Turning the area into a public square might have been a good option if it had somehow considered how this could work alongside architect Javier Ferrero Llusía’s design, which was one of the finest examples of rationalist architecture in Madrid. In fact, its demolition in 1974 was highly controversial.

The market had its origins in the second half of the 19th century, when a growing number of street stalls began to set up in the square. In 1934, Ferrero received the assignment from the government of the Second Republic as part of a wider urban-planning program, which aimed to solve the lack of infrastructure at the time.

Furnished with a supply area and ramp for vehicles, its octagonal shape conformed perfectly with the shape of the square itself – the octagons went up in stages toward the center until reaching the central patio, which ventilated the whole.

The building’s demolition took place amid tension between city authorities, who considered the structure obsolete, and the local residents, entrepreneurs and architects who recognized its value.

7. Motocine, Madrid

In the Madrid district of Alameda de Osuna, there are still residents who remember this area as “the Motocine.” This recreational space was designed by the architect Fernando Chueca Goitia in collaboration with the engineer Bello Lasierra in 1959, an imitation of the successful US model of drive-in movie theaters. The US link was the reason for erecting the building close to the US military base in Torrejón de Ardoz.

It was the biggest drive-in cinema in Spain and the second biggest in Europe, managing to accommodate 700 vehicles which were expected to line up in front of the vast cement screen. There was also a protected seating area for bikers.

It was a simple building with modern touches evident in the entrance halls and in the efficiency of the facilities. But the project was either too ambitious or too naïve, and it failed to match the success of such establishments on the other side of the pond. Even the US military personnel from the Torrejón de Ardoz base did not use it as often as projected, and it closed after just a few years.

8. Monky Factory, Madrid

Built between 1960 and 1962, the Monky Coffee Factory was demolished without warning by its new owners in 1991 – a victim of property speculation. It was designed by Genaro Alas and Pedro Casariego and its transparent, expressionist features also doubled as a giant advertising campaign, as showing off the machinery within became part of its commercial strategy. It was a simple but effective tactic, which efficiently addressed industrial requirements and the aesthetics of its corporate image.

The building was designed to be seen from the road or, more specifically, from the N-II motorway connecting the capital with the airport. The main structure consisted of steel and glass, reflecting the basic principles of the Mies van der Rohe style of architecture, and seemed very modern for its day. It was this that allowed the 20-meter high stainless steel atomizer to be seen from the outside – the main piece of machinery used for producing the instant coffee.

Another lower structure with the same features housed the extractors while other buildings of exposed brick were used as offices and storehouses, harmoniously completing the complex.

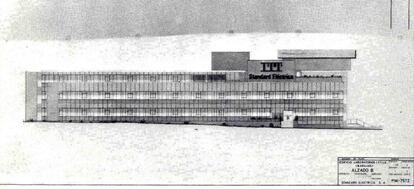

9. ITT Laboratories, Madrid

Despite its name, this building was not actually a laboratory but rather the headquarters of Standard Electric’s Center for Research and Development. Built between 1966 and 1970, it was awarded the National Prize for Architecture in 1972.

Also located on Madrid’s route to the airport, on Avenida de América, its high profile was due to its location on the side of the motorway and its double-armed shape, which anticipated future expansion.

Using traditional Spanish materials and designed to allow for plenty of natural light, the structure consisted of exposed brick and huge windows framed by iron latticework, in the Neo-Mudejar or Moorish revival style. Meanwhile, the turrets were obscured by a simpler lattice design.

However, changes in urban-planning legislation prompted the owners to demolish the building after just 30 years, to make way for a more land-efficient design with no consideration for its architectural value.

English version by Heather Galloway.