Shipwrecks of the Caribbean: Spain drafts treasure map of its own days of empire

The Culture Ministry has charted the 681 vessels sunk between 1492 and 1898, including the Santa María, the largest of Christopher Columbus’s three ships on his first voyage across the Atlantic

If Long John Silver had got his hands on the first inventory of Spanish shipwrecks in America, he would promptly have deserted Treasure Island and headed for the Caribbean, map in hand.

He would then have made his way to the spot where Christopher Columbus’s ship, the Santa María, went under. He would also have managed to locate the ships lost by Hernán Cortés when he led expeditions in modern-day Mexico or those commanded by Francisco Pizarro or Vasco Núñez de Balboa; all this plus the coordinates showing where the sea swallowed up vast troves of gold, silver, emeralds and exquisite pearls.

It would have taken Robert Louis Stevenson’s bounty hunter several lifetimes to raid the 681 ships documented by the Sub-Directorate General of Historical Heritage of the Culture Ministry over a period of five years. But at the end of it, he would have known a great deal about the history of Spain between 1492 and 1898. The vast project was coordinated by marine archeologist Carlos León, along with his colleague Beatriz Domingo and the naval historian Genoveva Enríquez.

Hundreds of pages from the General Archive of the Indies in Seville and Madrid’s Naval Museum have been scrutinized, along with 420 old maps in order to create the most extensive guide to Spanish shipwrecks and treasure to date, and which is part of the National Plan for the Protection of the Cultural Underwater Heritage of Spain, developed according to the UNESCO Convention of 2001.

The Spanish empire was founded on two pillars: the army and the navy. But behind both was a silent but effective army of civil servants whose job recording the details of each expedition now allows for the location of ships that went under in waters off Panama, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, the Bahamas, Bermuda and along the US Atlantic coast. Rather than rescuing these ships from the depths, the aim is to protect them from treasure hunters or from damage, in cooperation with authorities from the corresponding countries.

The first ship to sink off the coast of the Americas was the Santa María, which went under on Christmas Day, 1492. Not having slept for two days, Christopher Columbus had shut himself in his cabin and gone to sleep, handing over the command to the steersman, who also decided he was tired and in turn handed the ship over to the cabin boy. With the boy at the wheel, currents carried the ship onto a sand bank off the coast of Haiti where it sank the next day. Furious, Columbus ordered the crew to strip the ship and use the timber to build a fort, enlisting the help of the local Taino Indians. He called the fort Navidad because the ship had sunk on Christmas Day.

The Indians wore small pieces of gold around their necks, which they quickly exchanged with the explorers for trinkets of little value. What at first had seemed like a disaster, turned into what would become the first Spanish foothold in America. Columbus left some of his men behind on the island while he returned to Spain to inform the Catholic Kings of his discovery, and in the meantime these men were soon massacred. As the ship was not entirely stripped for the construction of the Christmas fort, remnants of its wreck are still evident.

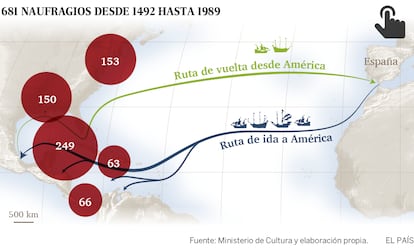

Only 23% of the 681 ships have been explored so far for archeological purposes. Most of the wrecks can be found off Cuba (249), followed by the US Atlantic (153), an area famous for its pirate islands, and Spanish Florida (150), an area that stretched throughout what is now the states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia and Alabama. Panama, for example, has 66 wrecks and the Caribbean island of Hispaniola has 63.

But why were so many ships sinking during that period? Carlos Léon explains that 91.2% of the vessels that went down were struck by bad weather and only 1.4% were sunk on account of conflict – 0.8% as a result of run-ins with pirates. “The stuff about pirates is little more than myth,” he says. “The Spanish ships were fearsome and armed to the teeth and would be carrying dozens of cannon. They would have scared off the pirates rather than the other way around.”

If these enormous ships went under, the death toll could be up to 1,000. Five ships from Juan Menéndez de Avilés’ fleet sank in 1563 in Bermuda, with 1,250 fatalities. Six hundred more died when the Conde de Tolosa was wrecked in 1724 off the coast of Dominican Republic. In this case, there were only seven survivors who lived for 33 days on pumpkin and seawater while hanging on to the main mast for dear life.

There are wonderful tales of survival connected to these shipwrecks, some of which could put Treasure Island in the shade. In 1584, the survivors of the Santa Lucía, which was under the command of Juan López, used rafts to reach the coast of Bermuda where they found seven other shipwrecked Spaniards who had been living there for two years. Together they built a vessel and crossed the Caribbean in a straight line for 900 kilometers, which brought them to Puerto Plata, in modern-day Dominican Republic.

The inventory of the Culture Ministry pinpoints the exact location of each shipwreck, gives the name and style of the ship, the name of the captain, the weapons aboard and the number of crew and passengers. Besides Christopher Columbus, who also lost the Vizcaína in Panama, other famous names include Vicente Yáñez Pinzón who lost two ships in 1500 in Abrojos, Dominican Republic; Juan de la Cosa and Núñez de Balboa, who lost two ships in Haiti in 1501, Francisco Pizarro, who lost one ship in Nombre de Dios, Panama, in 1544; Pánfilo de Narváez, who lost two ships in Trinidad in 1527, and Álvaro de Bazán, who lost two ships in Santo Domingo in 1553.

Even inside the ports, royal fleets also sunk by the dozen. In 1768, 70 ships were wrecked by a hurricane in the port of Havana, and 60 more were sunk at the same spot in 1810.

Spanish ships carried a varied cargo. Experts talk about gold, silver, emeralds, ivory, but also Ming pottery, tobacco, sugar, vanilla and cocoa, not to mention slaves, arms, books and religious relics from Jerusalem. So much wealth aboard caused skirmishes with the English and the Dutch. Such conflicts were responsible for the sinking of the Nuestra Señora del Rosario and Nuestra Señora de la Victoria in 1590 off Cape San Antonio, Cuba. And El Neptuno, Nuestra Señora del Pilar and Nuestra Señora de Loreto were toppled during a spat with the English, who were trying to access the port of Havana. Suffering a similar fate were the destroyers Christopher Columbus, the Furor, the Almirante Oquendo, the Infanta María Teresa and the Vizcaya, which were sunk by the US fleet in the battle of July 3, 1898 in the Spanish-American war.

Few wrecks from pirate attacks have been found, though there are several in Camagüey, Cuba, from 1603 and three ships from 1635. Also documented is the cargo thrown overboard by Juan de Benavides to avoid it being robbed by Dutch pirates in Matanzas, Cuba. The wretched Benavides never lost a single ship in battle but the Dutch stole 14 of his vessels, for which Felipe IV ordered him to be beheaded when he returned to Spain.

Many of those on board sinking vessels simply drowned, but reaching land or keeping afloat did not always guarantee salvation either. In 1548, the entire crew of a ship that had been wrecked in the Florida Keys survived but were captured, used as slaves and killed by the Calusa, a Native American tribe. There was just one survivor: Hernando de Escalante, 13, who lived for another 17 years among his captors until he was rescued by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in 1565.

In 1605, the Santísima Trinidad left Cartagena, Colombia, only to be destroyed by a storm near Santa Isabel, Cuba. There were 36 survivors who got in a longboat along with the gold and silver cargo, which subsequently sunk from the weight. Two years later, a ship ran aground on Tienderropa beach in Panama. There were 13 survivors who reached the coast only to be killed by the Cimarrons, African slaves who had fled the plantations.

The Culture Ministry has only finished part of what will become the Spanish empire’s treasure map. Still left to cover are the wrecks in the Pacific, the South Atlantic and the Philippines, which will give a better idea of the integral volume of Spanish maritime traffic between the 15th and 19th centuries and the exact number of ships that were lost.

The importance of Florida

The Spanish monarchy spent enormous amounts of money in Florida, an area devoid of gold, silver, or indeed any natural resource. In fact, Felipe II became exasperated by the huge investments he was advised to make there by the military command. But the strategic importance of Florida resided in the fact that the peninsula created fast-moving currents that whisked ships loaded with precious goods back to Spain. If the British or French were to seize it, Spanish vessels would have a far harder time getting home. So they established a colony there in 1565 and built forts of stone to replace those of wood, which can still be seen today, though the territory was ceded to the US in 1819.

Besides carrying officially recorded cargo, these ships were also used to smuggle goods into Spain, which makes it hard to be precise about what exactly was on board.

In the Nuestra Señora de la Pura y Limpia Concepción, there are pieces of silver fashioned to look like cork tops and in the Guadalupe that sailed in 1724, a collection of more than 600 decorated glasses have been found.

If the contraband was discovered on arrival, the ship’s captains would offer excuses, ranging from not realizing that goods had been smuggled on board, to having lacked the time to record everything. One Franciscan monk claimed that as he hadn’t planned to come to Spain “he did not think to register the gold and silver he was carrying.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.