A booming market for charlatans

We have to accept that democracy requires more effort than just casting a vote every few years

Sixty years ago, CBS had a hit western called Trackdown. In one prophetic episode titled “The End of the World,” a huckster arrives in a quintessential western town and summons the townspeople to come hear his urgent news.

A “cosmic explosion” is about to take place that will end the world, he says. But he can save them. Him and only him. To survive they must build a wall around their homes and use special umbrellas that deflect the fireballs that will rain down from the sky – and which he will sell them. The name of the quack that stars in this episode? Trump. Walter Trump.

In the episode – which is available on YouTube – Hoby Gilman, a Texas Ranger who represents common sense, tries to persuade his neighbors to stop listening to Trump. “How long are you going to let this conman walk around town? He’s a fraud!” he tells them. Just like his real-life namesake half a century later, the Trump from the TV western deploys lawyers to neutralize his critics and rivals: Walter Trump threatens to sue Texas Ranger Gilman.

Charlatans and conmen have always existed. They are scoundrels who, leveraging their skills for persuasion, manage to sell some type of product, remedy, elixir, business, or ideology to unsuspecting people who believe that the charlatan will – without much effort – redeem their sorrows, alleviate their pains, or make them wealthy.

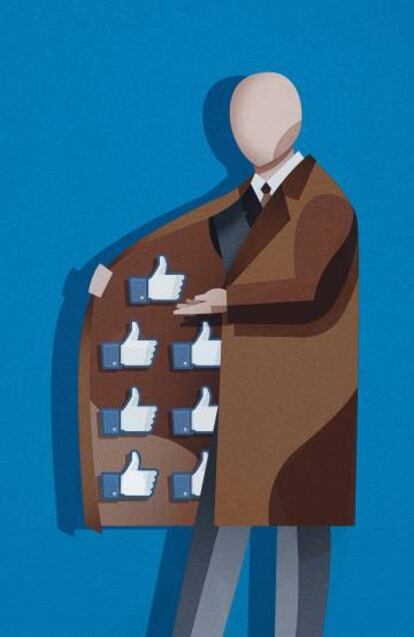

Lately, the market for quackery – especially in politics – has reached new heights. The demand for (and supply of) simple solutions to complex problems has skyrocketed. Demand is being driven by one crisis after another, while social networks are boosting the quacks’ ability to supply simplistic solutions to large audiences.

It would be a mistake to assume that digital charlatans are only meddling with elections in the United States

The current plethora of global crises is the result of powerful forces: technology, globalization, crime, corruption, bad governments, racism, xenophobia, economic instability, and inequality among others. The result is the proliferation of societies where many people feel rightly aggrieved, frustrated, and fearful of the future. They make up an irresistible market for charlatans who offer simple, instant, and painless solutions.

In the 1958 television series, an anonymous narrator tells us what happened: “The people were ready to believe. Like sheep they ran to the slaughterhouse. And waiting for them was the high priest of fraud.”

Half a century later, these phrases are ever more relevant. There are more and more societies willing to vote for the candidate who makes the simplest promise and who, in addition, says he will break from the past and take power away from the “establishment.”

The tricksters of today are, in essence, similar to those who have always existed, only now they have access to technology that gives them heretofore unimaginable opportunities. They are digital charlatans.

The clandestine intervention of one country in the elections of another nation is a good example of old practices that have been “super-powered.” Today’s digital charlatans operate through online bots. Bots use software algorithms to disseminate targeted information through social media to millions of users based on certain characteristics such as age, sex, race, location, education, religion, social class, political preferences, habits of consumption, etc.

Like all good charlatans, bot administrators know how to identify people prone to believe them. Before, hucksters used their intuition to identify their victims; now they use sophisticated algorithms and micro-targeting. Once their victims are identified, the creators of the bots send messages that confirm and reinforce their victims’ beliefs, fears, hopes and prejudices. Digital charlatans know how to stimulate certain behaviors in their target audience (vote for a candidate and defame their rival, support a certain group and attack another, disseminate false information, join a group, protest, make donations, etc.).

The tricksters of today are, in essence, similar to those who have always existed, only now they have access to technology that gives them heretofore unimaginable opportunities

These new digital technologies have another interesting characteristic: they can be simultaneously global and individualized. Their makers can concurrently contact millions of people and make each one of them feel that they are interacting in a direct, personal, and almost intimate way with someone who shares their values, goals and way of thinking.

This is exactly what happened in the US elections that took Donald Trump to the White House. The consensus of the US intelligence community (as well as those of other countries) is that this was a brilliantly designed and executed operation financed – at very low cost – by the Russian government, under Vladimir Putin’s direct supervision.

But it would be a mistake to assume that digital charlatans are only meddling with elections in the United States. Some 27 countries have likely been victims of political interference orchestrated by the Kremlin. Both in the crisis of Spain’s Catalonia region and with Brexit, intense bot activity and other forms of digital manipulation were detected, and the evidence shows they were controlled or influenced by the Russian government. The Kremlin has set out to sow chaos and confusion and to sharpen social conflicts in pursuit of a broader goal: to weaken its Western rivals.

In fact, one of the most revealing facts about the impact of the modern charlatans was the Google searches after Brexit. That is, after the United Kingdom decided – by a margin of only 4% – to get a divorce from the rest of Europe. “What is Brexit?” was one of the most frequently searched-for questions after the referendum was decided. Keep in mind that many of the claims and data used by the pro-Brexit campaign were known to be false. It didn’t matter: just like the townsfolk in the 1950s television series, “the people were ready to believe.”

The same goes for Donald Trump’s mendacity. According to The Washington Post, Trump made a staggering 7,645 false or misleading claims in 710 days as president, about 11 a day. Last October, speaking at a rally in Johnson City, Tennessee, the president made a whopping 84 false statements. This fact-checking by what he calls the mainstream media doesn’t seem to bother the president, as he knows that, like his old television namesake, “the people are ready to believe him.”

The people who get taken in by charlatans are just as guilty or even more guilty than the charlatans themselves

All this points to a regrettable reality: the people who get taken in by charlatans are just as guilty or even more guilty than the charlatans themselves when they allow their society to support bad ideas, choose bad rulers or believe their lies. Often the followers are irresponsibly uninformed, lackadaisical, and willing to believe in any proposition that seduces them, however preposterous.

This has to change. As we leave 2018 behind, we must face the fact that we have made life too easy for charlatans and we have been too accommodating of their followers. We must rebuild the capacity of society to differentiate between truth and lies, between facts confirmed by incontrovertible evidence and propositions that merely make us feel good, but offer solutions that are not really solutions at all or, worse, aggravate the problem.

We need more education about the uses and abuses of information technology and we have to accept that democracy requires more effort than just casting a vote every few years. We have to be better informed, keep an open mind to ideas that are at odds with ours, and develop the critical sense that alerts us when we are being manipulated. The need for governments to take action and create rules and institutions that shield consumers from the predatory behaviors of social media companies is becoming increasingly apparent.

Above all, we must develop the ability to differentiate between well-meaning, decent leaders and the charlatans who are out to con us.

Twitter @moisesnaim

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.