Humanitarian crisis looms as flow of Venezuelans into Colombia continues

Living conditions are tough in border town of Cúcuta, across from the Simón Bolívar bridge

“Imagine a city the size of Barcelona that was relatively rich a few years ago but which now has no food in its supermarkets, no medicine in its hospitals, and where protesters are persecuted: that’s what we’ve escaped,” says Susana Guevara, one of the thousands of Venezuelans who have fled the country.

Food insecurity affects 90% of Venezuelans

At the end of last year, she left Caracas with her mother and two children: three-year-old Ángel Gustavo and five-year-old Ángel Gabriel. The youngest shows signs of malnutrition, the eldest has leukemia and rickets. “That’s why we came. There was no medicine to treat him,” explains Guevara. “And because the political repression is unbearable,” she adds.

Guevara is a radiologist who began to protest the political situation in Venezuela when she was 17 years old. She was arrested multiple times. Then one of her kids was kidnapped. That was the tipping point. She left her house “with a poorly packed suitcase quickly thrown together, almost without savings.”

She left behind her husband, a supporter of President Nicolas Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chávez. After a 30-hour journey, she arrived at the Simón Bolívar bridge at the border between Venezuela and Colombia. She crossed into Cúcuta and joined the nearly one million Venezuelans who fled to Colombia last year.

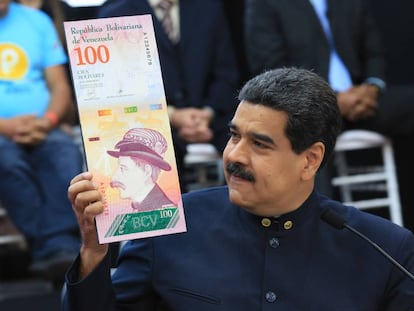

The reasons to leave are compelling: eight in 10 Venezuelans live in chronic or severe poverty. Hyperinflation has eaten away at their savings and salaries. GDP has fallen by 40% in the past three years. Food insecurity affects 90% of the people. There’s not enough medicine or doctors – 6,700 physicians are among those who have fled. And above all, they are scared. “The government has been repressing dissent through often-violent crackdowns on street protests, jailing opponents, and prosecuting civilians in military courts,” reads a UN report on Venezuela.

Every day, around 4,000 Venezuelans cross the Simón Bolìvar bridge into Colombia in search of a better future. Many will never return. But on the other side of the border, things are not much better.

“In the beginning we rented a room but our money ran out and we lived in the street until a shelter took us in,” recalls Guevara, whose plan is to get to Peru where she believes her son will be able to receive proper treatment.

In Cúcuta, unemployment is at 16.5% and the informal economy is over 50%. Public services are stretched thin and there is incipient xenophobia against Venezuelans. Making matters worse, Cúcuta is a hub for drug trafficking and listed as one of the 50 most violent cities in the world as guerrillas and paramilitary groups continue to clash.

The political repression is unbearable Venezuelan Susana Guevara

What with the dust, squalor, sickness and pollution it is an ironic destination for the thousands of Venezuelans who literally sell everything they own on the street just to survive. Even their hair – which goes for 70,000 pesos (€20).

Twenty years ago it was Colombians who were fleeing into Venezuela. Today the situation is reversed. Venezuelan Interior Minister Jorge Rodríguez recently said, “We will prepare a plan to invite Venezuelans to return,” but not many are likely to take up the offer.

Peter Rojas for instance, a 42-year-old former police chief, escaped Venezuela with one of his children after receiving orders to “suppress” a member of the opposition. Today Rojas, who did not want to use his real name, is wanted for treason and insubordination. He could be locked up for 30 years. He sold everything he owned at the border for 400,000 pesos (€120). They promised him passage to a different country but “they scammed me” he says, “and now the only thing left is to request refugee status but that will prevent me from working for a year. I’m desperate. I have two more children back there.”

Next to him is a woman who is pregnant with twins and has been begging on the streets for days to raise money for diapers. There are young mothers looking for vaccines for their babies which are not available in Venezuela. The list goes on.

“Hundreds of Venezuelans are arriving without end: at this rate the situation will soon become unsustainable,” says Willinton Muñoz, director of the Scalabrini Foundation Migration Center in Cúcuta.

If there is one image that defines the crisis in Venezuela it is this: the mass exodus of a generation shaken by forces beyond their control.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.