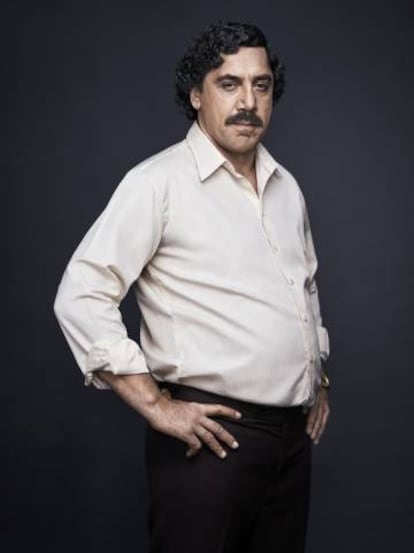

Javier Bardem: “Evil has its appeal”

Often cast as the villain of the piece, the Spaniard is one of the most highly respected actors of his generation. The soon-to- be-released ‘Loving Pablo’ sees him playing drug baron Pablo Escobar, but as he explains in this interview, having two children is proving a bigger challenge than any other role he has played so far

Javier Bardem has built his career on four pillars: luck, preparation, choice and perseverance. Add to that his powerful features and a virile demeanor, and you are left with a potent combination that has earned him a hallowed place in Hollywood, where he is now considered one of the big guns on a par with Sean Penn.

From a family of actors, his career has taken him further than any other Spanish artist on the international stage and won him a string of accolades, including an Oscar, a BAFTA and a Goya. Currently, he is in the middle of promoting Loving Pablo, which he co-produced with his wife Penélope Cruz, who plays journalist and lover Virginia Vallejo to his Colombian drug lord, Pablo Escobar.

But fatherhood and activism are also making significant demands on his time nowadays. He and Penélope’s two children, Leo, seven and Luna, four, like him to come home as daddy, as opposed to Pablo Escobar. He is struggling to find a balance between showering them with love and allowing them room to breath. Meanwhile, his sense of solidarity has recently taken him to the Antarctic to protest against the melting ice caps, and to boost the profile of the Greenpeace campaign.

He arrives promptly for the interview at Madrid’s Wellington Hotel wearing sports duds and a baseball cap, which he uses to obscure his face. Curiously, when he says hello, he comes across as almost shy.

Question. Loving Pablo is the result of 10 years of work with your friend, director Fernando León de Aranoa. What was it about Virginia Vallejo’s book that made you want to make the film?

Answer. Apart from the romance, there were details that brought the 1980s to life. Virginia – to whom we’ve spoken several times – fell in love with Pablo. She also fell into a blind alley she is still trying to get out of. But the book has some fantastic anecdotes about two people who see themselves as king and queen of the world.

To find someone else’s soul, an actor has to forget about himself. It’s a job that stops

you from being too critical because you’re forced to understand

Q. After 10 weeks of shooting in Colombia, did you feel differently about Escobar?

A. I spent years researching this, but when you get to the place and see the slums of Medellín where he grew up, it’s easier to understand where he was coming from as well as his excessive ambition and the social commitment that he conveniently used as a way of making himself more powerful. He invented narcoterrorism and turned himself into public enemy number one, a guy who made a fool of the state. His death was of national significance and perhaps that’s why we’re still speaking about him.

Q. When the Colombian President arrived in Puerta del Sol in Madrid and saw the poster for the TV series Narcos, he didn’t appear to appreciate its entertainment value.

A. And I get that. Some people are still taking flowers to Escobar’s graveside but most hate him and their memories of him are terrible. They were imprisoned by a story that involved a lot of death and fuss. For a guy like that to thrive, society had to be corrupt and there had to be a hierarchy that didn’t care what he was doing. When the state later declared war on him, there were many who didn’t want to know.

Q. How do you prepare for a part with so many subtleties?

A. That was one of the reasons I wanted to do it. I have been offered a lot of Escobar roles but there was always something that stopped me. I could only see coarseness not color in the other versions. The physical side of him interests me. After a lot of reading and watching interviews with him, I came to see him as a hippopotamus – his favorite animal – which has his energy and also the cold-blooded mindset needed to commit atrocities. He was a guy who took his time but who had everyone else chasing around. For an actor, it was a luxury.

Q. As a method actor, what’s harder – getting inside a character’s skin or shedding it afterwards?

A. I started acting when I was 19 and I’m now 49. I’ve been around and there are roles that have been really hard to shake off. Age, experience and common sense help you to disentangle yourself emotionally but I don’t know if that’s the case intellectually. For a while, you keep thinking about this figure that you’ve created, though that hasn’t been the case with Escobar. When they said, ‘Cut!’ I left him there. Also, I was working with my partner and taking work home when you have two children becomes very complicated.

The backlash against abuse is extraordinary but we are crossing dangerous lines. One

allegation on one media site does not make someone guilty

Q. You met your wife when she was 16 in Jamón, Jamón. Much later, Woody Allen brought you together again in Vicky Cristina Barcelona. Now, as a married couple, you have worked on Loving Pablo, and you have just finished shooting in Madrid for the Iranian director Asghar Farhadi. Are there advantages in working together?

A. The personal angle is difficult to ignore, but now we are adults, it pushes us to enter into an imaginative and creative game in which what matters is what you imagine and what that awakens in the other. It’s something that obliges you to get over the personal barrier and climb into the fiction, which is, in fact, what acting is about.

Q. You played the killer in No Country for Old Men and the blond cyber-terrorist in Skyfall with Daniel Craig. Do you like playing the bad guy?

A. Well, uh…yes. [Laughs] But within those parameters, their characters are very different. I look for nuances. If there’s enough material to build a character then I accept. Silva [from Skyfall] or the Coen’s protagonist come at destruction from different angles. There is something behind the evil that attracts – you have to root around to find out what’s made them monsters. In No Country For Old Men, my character showed no sign of humanity and that was the challenge – getting into the skin of a very warped human being, like the ones we unfortunately come across so often in the newspapers.

To find someone else’s soul, an actor has to forget about himself. It stops you from being too critical because you’re forced to understand them.

Q. Do you still get help with roles from your acting coach Juan Carlos Corazza?

A. It’s somewhere I’ve been going since I started acting. I am blessed to have found someone who helps me both personally and professionally. I admire the way he gets to the truth of fiction – as Liv Ullman said, unmasking it and turning it into something moving and sincere.

Q. Carmen Maura divides directors into two camps – those who talk a lot and those who don’t speak at all. Which do you prefer?

A. [Laughs]. I’ve been very lucky with the people I’ve worked with. The Coens and Woody Allen belong to the group who don’t speak and the others… Julian Schnabel has so many interesting things to say that I never get tired of listening to him. Each director leaves his mark but as the years go on, I can see that cinema is, as Fernando [León de Aranoa] says, increasingly an artistic discipline controlled by money. You’ve got to keep to the budget, even in major productions. I saw that in Pirates of the Caribbean. I admire those who can still find inspiration and courage in this environment.

Q. Hollywood has embraced you as one of their own to the point where your character in No Country for Old Men has appeared in an episode of The Simpsons.

A. It’s all been accidental. When young people ask me to give them advice, I use a phrase from [Spanish novelist] Cela: ‘I don’t give advice, people have to make their own mistakes.’ It’s good to be prepared for the ‘accident’. Bigas [Luna] said that a career is half luck, 25% preparation and 25% choice and perseverance.

Q. I imagine that meeting Bigas Luna was a milestone in your career.

A. He gave me my first role in The Ages of Lulu, a difficult character that I had to play in a brothel in front of my mother, who ran the brothel. I owe him my career. I adore him.

Q. Who keeps your feet on the ground?

A. My family and friends, although I think that it’s partly down to how you were brought up. I grew up in a family of comedians and I have witnessed my mother struggle with too much work and periods with none. I remember how she was always waiting for the phone to ring and the effect it had on the money we had. One thing I have branded on my brain about this profession is that you have to be able to step back from it. If you can’t see yourself doing anything else, you have to accept everything it entails, the failure as well as the success. You have to know how to deal with it all.

Q. With fame too?

A. When I did Jamón, Jamón, I was suddenly popular and I would go out and people would recognize me. It felt strange. I don’t feel comfortable with that kind of recognition.

Q. Now you’re recognized everywhere you go.

A. It’s been difficult to get used to but I have taken it on board, although I have denied being me before now. I have never had a problem with fans but I have received abuse in the media and I’ve also had a problem with people being all over me for an exclusive. I don’t remember any uncomfortable incidents out and about, either in Spain or abroad. There are people who are kind and fun who also come up to me to tell me that they like what I do.

Q. What sacrifices has fame forced you to make?

A. The possibility of being invisible, to observe without being seen, but I look for ways that I can observe because that’s part of my job and how I find inspiration. I go on the Metro a lot and for every 10 times I go, five times I get a phone pointed at me for a photo. I look for the right Metro lines and the best times to go, but I always notice some guy staring on the other side of the carriage.

Q. It is said you preferred fights over math at school. Have you become more serene?

A. Yes, but I didn’t enjoy fighting. In fact, I was a bit of a coward, although I’ve boxed and done martial arts. I got rid of my aggression on the rugby pitch and I still like the physical side of things. I’m not an intellectual although I live very much in my head, more than I would like. I’ve always been very instinctive, so much so that sometimes when it’s too late, I think, ‘How could I have said or done that?’ – although that has also helped me as an actor. You have to be hungry artistically, and refuse to be spoon-fed. You have to realize you have things to learn, that you don’t know it all and that it

takes hard work, but you can get there.

Q. It sounds like the American Dream

A. I’m a bit of a product of that – a random accident. I have been lucky enough to have gone through bad times, but then get called up by Bigas and Julian who saw me leaving a party and wanted to know if I was actor. He had seen Live Flesh but I was also in the right place at the right time. Life has shown me so many things that not a day goes by that I don’t feel grateful.

Q. When it comes to your children, you lack a mentor though you have your mother’s example.

A. Bringing up children is the most difficult thing I’ve had to do. Sometimes, what you know is not enough. I understand how difficult it is for people who are extremely busy to listen to their children, particularly if they’re small. Bringing them up starts there and it requires dedication. When you get home, they want to see their father, not Pablo Escobar. There’s a U2 song I like a lot that goes: ‘You’ve seen enough to know it’s children who teach’. Nowadays, I have a lot of friends who are parents and we talk a lot about how to show affection to our children without smothering them.

Q. The Bardems are like a brand in Spain. Do you think you are regarded with affection?

A. On a personal level, very much so. When I go out with my mother, people come up to her to kiss her and shower her with affection. The AISGE [the Spanish actor’s association] paid tribute to her in front of 1,500 people and they have also given her the Film, Aid & Solidarity Award. Obviously there are people with different ideas from ours but we welcome that. The only thing disqualifying anyone are insults and aggression, although at times we have also been aggressive.

Q. People say you can’t be rich and left-wing. Do you think that’s so?

A. Rich… More like living from my work and living well. It’s money I’ve made working. I haven’t robbed anyone and I’m not extravagant. I save and I still have the money from films I made seven years ago. I don’t splash out, I keep it. It makes you wonder if you need to live under a bridge before you can speak about social justice. It’s curious that so many people come up with: ‘If you have this, you can’t speak about that’ because it impoverishes us and it’s a means of undermining someone.

Q. Nowadays people who speak out have to be prepared to listen to different opinions or be subjected to the justice dealt out by Twitter.

A. Of course. But I don’t have anything to do with social media justice. My generation has had to deal with the media epidemic first hand and it’s very hard. You say something and in 15 minutes it’s on the far side of the world, for better or worse, but it’s been very aggressive.

Q. The Harvey Weinstein scandal has triggered something of a revolution and the #MeToo campaign is unstoppable. How do you feel about blacklists?

A. My parents were divorced when I was two. I have always lived with my mother who is a very strong woman and my upbringing was very feminine and I think I know about male-dominated society. That said, it’s a good idea to be careful about what you say. On one hand, the backlash against any type of abuse is extraordinary, especially with regards to gender and inequality, whether it’s to do with morality or money. But we have to take care because we are crossing dangerous lines, as in everything that is said or published on one media site can make someone guilty, with the personal and professional damage that entails and with no chance to defend themselves or to have

access to a fair trial.

Q. One of the most recent celebrities to stand accused is the photographer Mario Testino.

A. I don’t know about his case. But there could be people out there who hate you and who could say dreadful things to get revenge. It’s important to remember that we have a right to be presumed innocent. Obviously I’m not talking about Harvey Weinstein, where there is so much widely shared evidence, but every day new names are coming up and, of course, most or almost all the stories will be true, but there needs to be a legal process. People should continue to make allegations but take care when doing so. It’s a little terrifying. It gets to a point when anyone could be the victim.

Q. You have worked with Woody Allen, who some feminists now refer to as a monster. Should art offend?

A. Art should be free. I don’t like the idea of censoring a work of art because it contains a scene with a teenager in a sexually provocative position. It would mean Lolita would never have been published.

English version by Heather Galloway.