Was Hemingway’s macho posturing merely a front?

New biography exploring author’s sexuality suggests divide between virile figure of novels and reality

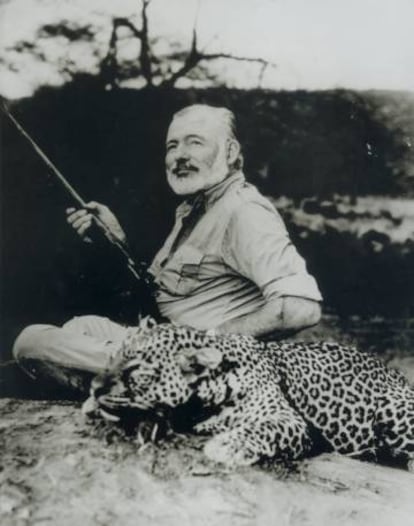

Born in 1899, Ernest Hemingway was fanatical about boxing, hunting, fishing and bullfights. He fought in three different wars and came home a hero. He went on expeditions to Africa where he hunted big game. And his treatment of women is often portrayed as cruel and abusive. In short, he created a paradigm of virility against which men were measured throughout the 20th century. Even his writing was red-blooded, with lyricism, metaphors and elaborate descriptions ditched for brief and punchy prose. This testosterone-charged image was one he would take with him to the grave. The real Ernest Hemingway was, however, quite different. As Zelda, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unstable but lucid wife, pointed out: “Nobody can be that macho!”

A new biography by US writer Mary V. Dearborn sets out to explore Hemingway’s sexual insecurities. “It was part of what destroyed the end of his life,” says Dearborn, who has written about other icons of masculinity in the literary world such as Norman Mailer and Henry Miller and is the first woman to tackle Hemingway.

He was undoubtedly queer. He managed to avoid defining himself as gay. He shook up people’s expectations about sexuality Mary V. Dearborn, Hemingway biographer

Running to 750 pages, the biography examines all aspects of the writer’s life and work, but it is Dearborn’s study of Hemingway’s sexuality that sets it apart from the other tomes on the author. The book exposes his fascination for the androgynous and a hair fetish – he would ask his partners to wear their hair as short as possible while he let his own hair grow and dyed it blonde and auburn; if anyone asked he would say it was the sun.

On his return from his second expedition to Africa, Hemingway wanted desperately to get his ears pierced. “Wearing earrings would have a lethal effect on your reputation,” his fourth wife Mary Welsh said, by way of talking him out of it.

So was Hemingway a repressed homosexual? “The short answer is no,” says Dearborn. “He was undoubtedly queer. He managed to avoid defining himself as gay. He shook up people’s expectations about sexuality and the behavior of men and women,” she adds, pointing out that in his unfinished, posthumously published novel The Garden of Eden, Hemingway’s alter ego, a writer called David Bourne, asked his wife to cut her hair and then proceeded to sodomize her with a dildo, something Hemingway had done himself with Welsh. According to Dearborn, it wasn’t about being homosexual or a transvestite. It was about adopting the female role during sex. In fact, the writer was simply ahead of his time, opening up the possibilities of a more fluid sexuality that is talked openly about today.

“Nobody can be that macho!”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Hemingway was born in Chicago and lived there until he was six in a three-story Victorian house in Oak Park that he would later describe as “a place with wide gardens and narrow minds”. There is now a small museum dedicated to him in the same street. Inside the museum is a caricature of the writer printed in Vanity Fair in 1933 in which

Hemingway is depicted wearing a loincloth and putting hair booster on his chest. There is also a photo of the writer as a baby dressed in girl’s clothes, as was the custom in those days until the age of one. Hemingway’s mother Grace, however, continued to do this for years, bringing up Hemingway and his elder sister Marcelline, as though they were twins, dressing them identically – in boys outfits or girls, depending how the mood took her.

Trauma

This period of his life would prove very traumatic to the author, triggering an anxiety that would lead to an obsession about masculinity, according to a biography by Kenneth S. Lynn published in 1987. In light of this, Hemingway’s work is open to interpretation. Rereading the Nobel Laureate’s novels and short stories, what jumps out at you is not so much the superhero as the insecurities of the men. Like the main character in The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber, who is ashamed of having run away when shooting big game, many are trying to embody an impossible model of masculinity.

Hyper-masculinity was part of who he was Paul Hendrickson, Hemingway biographer

Biographer Paul Hendrickson, who wrote Hemingway’s Boat, doesn’t believe that Hemingway’s extreme masculinity can be considered an act. “Hyper-masculinity was part of who he was,” says Hendrickson, a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania. “It was real and authentic. Maybe it was a convenient mask for his ego, but it wasn’t fake. I believe he was heterosexual, but with many contradictory feelings concerning his sexuality. I’ve never found the slightest evidence that suggests he was attracted to men.”

Hendrickson also speaks about the difficult relationship Hemingway had with his youngest son, Gregory, a transvestite who finally had a sex change at 63. He died as Gloria in a women’s jail in Florida where he was imprisoned for indecent exposure. Once, when Gregory was small, Hemingway caught him trying on his mother’s tights. Later the writer would tell his son: “You and I come from a strange tribe.” According to Hendrickson, Gloria lived what her father could barely admit, even to himself. “Hence the love–hate relationship,” he says.

Meanwhile, Dearborn maintains that this was the prison from which Hemingway would never escape. “In a better world, Hemingway would have pierced his ears,” she says.

Hemingway museum in Chicago

The museum in Oak Park in the suburbs of Chicago has closed its doors 27 years after its inauguration with a view to using the funds from its sale to build a center for writing and investigation incorporating a bookshop and gallery, on a plot beside Hemingway’s birthplace. The foundation will also launch a campaign asking for donations to finance the project to the tune of €1.1 million.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.