Camilo Restrepo: the revolutionary architect of Medellín

A Harvard lecturer is one of the main urban renewal architects in the Colombian city as the country builds a fragile peace

Born in Medellín in 1974, Camilo Restrepo does not believe the architect is akin to God. “He’s more like the last in line,” he says modestly. “Basically, architecture is about setting political and economic decisions in stone.”

While Restrepo doesn’t believe a building can change lives, he does think it can improve them, as is evident from the projects on display in miniature in his office. Located on the ground floor of the G5 tower in the wealthy neighborhood of El Poblado in Medellín, the office is bathed in natural light for most of the day and has a freshness to it, enhanced by doors which lead out onto a garden filled with indigenous plants he placed there with his own hands.

The upper reaches of the building contain corridors and staircases that are open to the elements and lead eventually to a vast rooftop terrace with views over the valley that was once home to the most violent neighborhood in the world. Despite the city’s constant heat, a breeze blows through the entire building. It’s similar to the coffee drying unit that Restrepo has just built in Ciudad Bolívar, which he also wanted to turn into a cultural center to ease the isolation of the coffee growing families from the Andean region.

Architecture is about setting political and economic decisions in stone Camilo Restrepo

The hallmark of Restrepo’s work is his social and environmental agenda. A Harvard lecturer, he is the founder of the architectural agency AGENdA, which was one of the few chosen by the Chicago Architecture Biennial exhibition as having great potential for the future. On receiving the accolade, Restrepo talked about his area of expertise – architecture in the tropics. “Everything is the other way around in the tropics,” he explains. “What is closed off in the northern hemisphere is open here. What is defined there, is ambiguous here. And what is static becomes dynamic.”

Those principles were at work from the outset. Ten years after its inauguration, the Orquideorama in Medellín’s Botanical Gardens is a city landmark. Restrepo was just 32 when he designed it with the help of his father, veteran architect J. Paul. Restrepo. A vast space, shaded by an open canopy that protects the flowers from direct sunlight and collects and channels rainwater to water them, it is also used as a venue for exhibitions, concerts and fashion shows. “The ideas was that it would blend with the trees,” he says. “Basically, architecture and nature are human inventions. Both are equally artificial.”

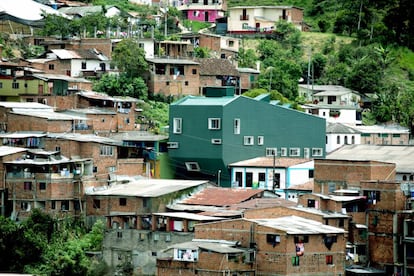

Restrepo has also been active in the urban makeover of Medellín, a city that was mired in violence and which is experiencing an unexpected renaissance. “Bold decisions will be taken, such as tackling marginalized neighborhoods with a social vision that drug trafficking managed to wipe out,” he says.

The recent truce between the military and the rebel FARC in Colombia has made Restrepo more optimistic about projects like these. “Like all peace agreements, it won’t be perfect, but it will allow us to cross a threshold and reinvent ourselves as a country,” he says. “After decades of seeing a violent response to disputes, architecture has a mission to create places for people to come together,” he adds.

Without wishing to sound too idealistic, Restrepo says he believes in happy endings. “To be an architect is to be optimistic,” he says. “Architecture can’t do magic but you hope your work will have a positive effect on others.”

English version by Heather Galloway.