One US county’s solution to drug epidemic: let addicts die

As opiate overdose rate soars in US, some in Butler County, Ohio, oppose spending public money on treatment

John Wayne, Muhammad Ali, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump.

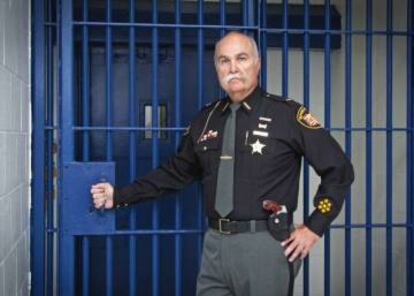

Butler County Sheriff Richard K. Jones of Ohio lives, quite literally, in the shadow of his idols. On the walls above his desk hang portraits of these men, together with two American flags and a Madsen machine gun from 1946, which can reach 2,800 yards at 600 bullets per minute. “This kills as much as heroin,” says Jones.

The sheriff is charged with watching over Butler County and ensuring its protection. Buried deep in the Midwest, it has only 376,000 inhabitants, but last year, reported 210 deaths from drug overdoses – almost half of that in Spain, which has a population 120 times greater. It is a devastating wave of opioids, and has now reached epidemic proportions. In 2016 alone, the death toll from opiate addictions in the United States was greater than the number of casualties it sustained during its 20-year involvement in the Vietnam War. And in this small county, it has led some leading citizens to propose a solution as unusual as it is simple: let the addicts die.

We have cases of addicts who, in one month, have suffered 20 overdoses Butler County Sheriff Richard K. Jones

The proposal has risen from the ruins of the American Dream. In the rust belt, large factories have shuttered their doors and the white majority, which once enjoyed high standards of living, is trapped in a memory. Job security, white picket fences and houses with perfectly trimmed front lawns have given way to fear and anxiety. Strikes are called in protest at dwindling wages. China, Mexico and other phantoms of the far right stand at every corner. “People want solutions and jobs. They’re fed up with the two parties,” explains Jones.

The sheriff, 6’3” in stature, with the mustache of a Viking, is the strong silent type. Not one to mince words, he carries two pistols at his belt and has all the answers.

“Drug cartels?”

“We have to drop the MOAB [the mother of all bombs].”

“A wall on the southern border?”

“Perfect for stopping the flow of heroin.”

“Attention to the victims of overdoses?

“That’s not the job of the police.”

“But lives…”

“You can’t put a price on lives. That’s why I want my officers to return home every night with their lives.”

A few weeks ago, Jones became a subject of controversy when he decided that his agents should not administer Narcan, a heroin antagonist that blocks the devastating effects of an overdose. This treatment, costing $40, provides a daily lifeline for thousands of addicts. And in a country where opioids have caused – in the last year – 1.3 million hospital visits, it is seen as essential. Its use by first responders is regulated and mandated in 38 states. But not in Butler County: just one of the many places in America where addicts are left to die.

“All we’re doing is reviving them, we’re not curing them. One person we know has been revived 20 separate times. We don’t give shots for bee stings. We don’t inject diabetic people with insulin.” says the sheriff. “I’m not the one who decides if people live or die. They decide that when they stick that needle in their arm.”

His words provoked outrage across the nation. Humanitarian organizations and doctors condemned his comments. Authorities turned their backs on the sheriff and even the district attorney has censured him. But he is not without his defenders. Some have gone even further.

Daniel Picard is a Republican, a Catholic and a distinguished member of the small community of Middletown (population 50,000) in Butler County. As a city councilman, he has proposed his own solution to the problem: at the third instance of an overdose requiring urgent care, if the affected person has not paid for the previous interventions (through either money or social work), the government will stop providing treatment.

Simple and straightforward: if they don’t have money, they die.

Sitting in his office, Picard tries to explain his initiative in numbers. “Overdoses are increasing endlessly. In 2016, we had 526 cases and 72 deaths, and in just the first trimester of this year, 596 cases and 54 deaths. Many are not from this town or their families don’t want anything to do with them, so City Hall has to take care of everyone. Each response to an overdose costs us $1,104, and each cremation, $700. It’s an out-of-control expense, and we have to make a decision. I’m sorry, but somebody has to do it,” he says with determination.

“And you don’t feel pity for the people who die?”

“If they fulfill their service requirements or pay upfront, they will be attended to. It all depends on them.”

In this country, if you fall, no one will help you. They want you dead Errol Monroe

Them. The others. The addicts. Sarah is one of them.

She is 27 years old. Born in the city of Hamilton in Butler County, she has never left Ohio. She has never even seen the ocean. She has been an addict since she was 13 years old. That is her world. Her father died from alcoholism, and her mother, after years of abusing painkillers, fell victim to an overdose of fentanyl-laced heroin.

Sarah has been to prison for breaking her parole. In her earlier years, she would steal and “do what she had to do” to continue dosing. She has narrowly escaped death on so many occasions she has forgotten how many times she has actually been saved. “There was one month that I had 18 overdoses. Without Narcan, I’d be dead…beyond dead. One night, they had to give it to me four times before I finally recovered,” she recalls.

Having been clean for eight months now, Sarah feels strongly that she owes her life to the emergency treatment. She does not understand the debate in Butler County. For her, saving lives is an obligation, and Narcan is the only way to do it. “If they take it from us, we die,” she says, bewildered by the proposals of Councilman Picard and Sheriff Jones.

What Sarah does not realize is that her story is one repeated across the nation. Just last year, 60,000 people lost their lives to the epidemic. It was the leading cause of mortality for people aged under 50: more than cancer, gun violence or car accidents. About 35,000 of those deaths were caused by heroin usage, the remainder, by the abuse of prescription opiates.

Over the last 15 years, opioid pain prescriptions have tripled, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). As a study in medical journal JAMA Psychiatry points out, 75% of heroin addicts start with these painkillers. They are the gateway drug to a market that Mexican cartels have perfected: a purer product at lower prices with better distribution. The combined result is the rapid availability of opiates and a growing base of consumers – as the epidemic has spread out of control.

The reaction in America has been late and ineffective. Congress has approved a $1.1 billion plan, while states are individually seeking their own way out. Maryland has declared a state of emergency, while the attorney general in Ohio has sued the five largest opiate manufacturers for causing addictions.

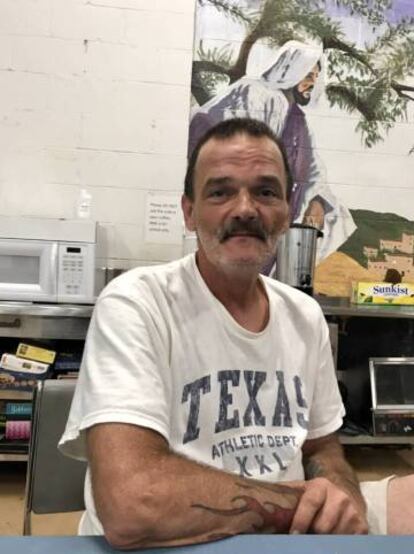

“In this country, if you fall, no one will help you. They want you dead. That is why they’re trying to get rid of Narcan,” says Errol Monroe, 57. He is a burned out junkie with tired blue eyes. In his youth, he was a mechanic, but a back injury left him incapacitated. To lessen the pain, he was prescribed pills. For 14 years, he took legal opiates until he discovered heroin. Cheaper and more powerful, $20 was all it cost for a taste of heaven.

He has sought refuge at a homeless shelter in Hamilton. He has little hope left, but his life, he declares, is not over yet. Despite adversity, he is fighting to give up heroin for his daughter. Aged 19, she too lives in Hamilton and is also a heroin addict, paying for her habit through prostitution. Monroe dreams of saving her. And it is only for that purpose that he fights on to live another day.

English version by Henry Hahn.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.