The odyssey of the new Europeans

Immigrants are at the center of an intense political debate in Europe. EL PAÍS is starting a series of feature articles to understand this phenomenon. The newspaper will be following a group of soccer players from Alma de África, a sports initiative in Andalusia to help undocumented migrants settle in Spain

Modu Dione is the latest signing. Senegalese, he arrived to Spain on a rickety boat. His father sells onions. “The markets there are not like the markets here. Stallholders sell one thing, not several,” he explains on a rainy February Sunday while watching his future teammates in Alma de África (Soul of Africa) win 2-0 at a municipal soccer pitch in Jerez de la Frontera. Modu, aged 26, will soon be joining this team of immigrants and several Spaniards, who play in the third division of Andalusia’s regional soccer league.

The 90 minutes of the Sunday match and the accompanying training sessions are the highlight of the week, a time to laugh, to bond with teammates, to forget the daily difficulties of life: unemployment, not enough money to pay the rent or to feed a family, not knowing sometimes where you’re going to sleep tonight or next month. Or the fear that your papers won’t be issued or renewed, or worse, that you’ll be expelled.

Dione and his teammates have discovered that life here is harder than they imagined when they left for Europe, many of them with the dream of becoming the next Samuel Eto’o or Zinedine Zidane. “The European system isn’t as easy as we thought in Africa, eh? There are a lot of things you have to learn when you come here,” says Yves Florent Fieusse, a 32-year-old defender from Cameroon who made it into Spanish territory from Morocco on New Year’s Eve 2011. Rodrigo Gómez of Cadiz-based NGO Accem agrees: “People still arrive here asking if they can work after being issued with an expulsion order. The lack of knowledge when they set off is significant.”

Alma de África isn’t going to find me a job, but I’m happy to have it in my life

Issa Abdou, from Cameroon.

The experiences of these soccer players, many of them still adolescents when they arrive here, provide a snapshot of the reality of life for immigrants in Spain. This is a group that has multiplied tenfold in two decades (4.6 million on the electoral roll, 10% of the population), but that has avoided generating tension or conflict in Spanish society, even after the 2004 bomb attacks in Madrid or during the economic crisis, when unemployment hit a peak of 26.9% – a figure that rose to 37.7% for immigrants.

Alma de África has a social mission as well as a sporting one. “We try to help them find work and deal with the administration, but it is very difficult,” admits Alejandro Benítez, aged 53, and president of the club. It doesn’t help that unemployment in Jerez de la Frontera, in Cadiz province, which has the country’s highest levels of joblessness, is officially 36%.

The team is now playing its second season, and has been covered by the media, attracting sponsors and around 50 season-ticket holders, but the search for finance and support for a third season has begun. The players are given €5 for playing and training, but the majority are without work, living from day to day.

Hicham Aidami, a 23-year-old winger from Morocco, found his last job thanks to Irene González, the club’s 32-year-old secretary, a community manager, and the daughter of the women who inspired Alma de África when she was looking for gardeners on the side’s WhatsApp account. Aidami and his fellow Moroccan Hamza Charafi, a 23-year-old who plays on the right wing and speaks English after spending time in London looking for work, were among the first to apply for posts. After securing the jobs, they had to find gardening tools: rakes, picks and shears. It was not easy, but they eventually succeeded, explains Irene: “I had to go to get it, because he didn’t want to walk down the street with a pick. ‘I’m an immigrant, I don’t want to risk something happening’,” she remembers him telling her. Hicham, who is currently taking his high school diploma, says the job lasted six days and he earned €9 an hour. “If only we could find another little number like that again,” he says.

When it’s not raining, Yves, the Cameroonian, sits under the same tree every day in a run-down area of Jerez and offers to clean cars. “Dry, inside and out,” he says, adding that the €300 he manages to rustle up each month is just enough to live on. He was taught the trade by his compatriot Eric Rafael Kameni, the 38-year-old defender and vice-president of the club, and that he taught to Abdulayemignane Diouf, the 21-year-old striker from Senegal known to his teammates as Abdul. He debuted for the side a couple of Sundays ago. The Moroccan talent spotter he left his home for tricked him, but he still dreams one day of making a living from scoring goals, despite the difficulties.

Life isn’t much easier for those in the team who have residency and work permits. The captain, Ahmed Moctar Fall Falle, a 21-year-old defender from Senegal known as Mahu, works for a travelling saleswoman who patiently taught him to speak Spanish, and then to read and write it. He cannot find better paid work to feed his wife and two children and to send a little something to his mother back home. “What I want is a good job. Here, you’re not going to find that, whether you are signed up [to Social Security] or not.” Papers and work; the two things that dominate their lives off the pitch.

Sánchez of Accem describes Alma de África as the social network that’s needed.” The equivalent to an extended family that has helped ease the crisis in Spain, as shown by the side’s rallying cry:

“What are we?” “A team!” they roar back.

“What are we?” “A family!” they reply.

“Who are we?” “Alma de África!”

The players of Alma de África are the Spanish link in a long-term project to follow immigrants and refugees as they settle in Europe. EL PAÍS is working in collaboration with The Guardian, Der Spiegel and Le Monde to provide a panorama of the phenomenon in four of Europe’s biggest countries. We will follow the soccer players of Jerez, as well as how an Afghan boy and his father are adapting to life in the United Kingdom, along with the fortunes of a Syrian family recently arrived in Germany and another family from Sudan that was refused permission to stay in Israel and that is going to settle in France.

The Jerez team was created thanks to the hard work of nurse Quini Rodríguez, who wanted to create something to remember her sister by. In the fall of 2013, María del Carmen died at the age of 56 from lung cancer after surviving a tumor on her uterus at the age of 30 and then breast cancer a decade later. Her brother also wanted to create something to remember this altruistic woman by. He eventually found it one Sunday as he was walking past the Pradera, a huge patch of open ground in the city that was once used for polo matches, and where he came across a group of Africans who were playing soccer. After talking with them, he promised to come back with a referee and a trainer. Two weeks later, he kept his word, returning with a childhood classmate and former Jerez player Alejandro Benítez, now the president of the club.

The players, all from Africa, with the exception of a Latin American, were mistrustful of the two strangers who suggested they create a team and join the lower leagues. Eventually, they returned, this time to ask for the players’ passports and identity papers. “That was when we saw that this was for real,” remembers Amed Soleto, a 26-year Bolivian who plays on the wing. “Initially, nobody believed it, but hell, when they came back with our registration documents…” adds Hicham.

Leaving aside their success on the pitch, playing semi-professionally with their own strip (donated) over the last two seasons before spectators has given the team a sense of pride. They have made the front page of local daily Diario de Jerez and even recorded a video clip with local flamenco-pop group Pompa Jonda in the Chapin stadium, home to Jerez CD. In 2016, Alma de África was awarded the city’s Equality and Integration Prize.

The majority of the players have been in Spain for long enough to speak Spanish well, even using the local pisha slang. Several now have girlfriends and wives from the host community. What’s more, they now play with five Spaniards, a decision taken to avoid being ghettoized.

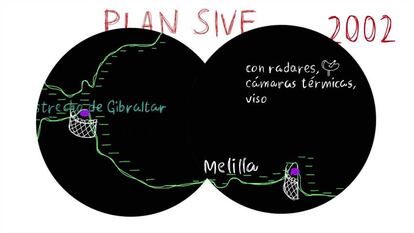

Exactly a year ago, as thousands of refugees and migrants poured into Greece, Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, issued a dramatic plea, calling on economic migrants not to risk their lives trying to make it into Europe. But many will have taken no notice. Some 350,000 immigrants arrive in Spain each year, according to the latest report from CIDOB, the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs. They are also arriving in the rest of Europe. In contrast, very few refugees have made it to Spain, which continues to apply very restrictive asylum policies.

“The numbers of immigrants leaving was clearly higher than those coming in for a brief time [during the economic crisis],” says Joaquín Arango, Professor of Sociology at Madrid’s Complutense University, and who coordinated the CIDOB report. This was between 2009 and 2012, and mostly affected people without papers, he explains. Arango highlights some notable changes to immigrants in Spain. Eight out of 10 have residence because they were able to show that they had put down roots here or regularized their situation through amnesties (at one point there were 1.5 million immigrants without papers here). Accem, which houses several players in the side in apartments, has the unwelcome task of telling new arrivals to Cadiz without papers that they must spend three years here before they can begin the process of regularizing their situation.

The future of these soccer players is uncertain: several are weighing up whether to move in search of work, while several will soon no longer be able to stay in the apartments ceded to them by Accem. Another is waiting for the paperwork that will allow him to marry, while one player’s residence permit runs out in several months.

More than one million immigrants have obtained Spanish nationality. Amed has begun filling in the paperwork. He’s seen as somewhat privileged among his teammates because he lives with his parents (who now have Spanish nationality, but who were originally undocumented) and because he arrived in Spain by plane. He may have had three stopovers, but it was nothing compared to Yves, Kameni and Issa’s feat in climbing over the razor wire that guards Spain’s two exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco, or Mahu, Abdul and Modu’s voyage in a boat, or Hicham and Hamza’s journey clinging to the underside of a truck.

Alma de África has been described as an extended family that has helped ease the crisis in Spain

The massed assault of the fence at Ceuta by 498 Africans in February hit the headlines as the largest such attempt to break into the European Union’s only land border with Africa, but the majority of foreigners reach Spain by plane or bus with a tourist or student visa, and when it runs out, they become undocumented. At present, the number of such irregular entries into Spain made up just 0.4% of the total in 2015.

“The fences, visas, fines imposed on airlines [that allow passengers without a visa to board] are all aimed at supporting a system that forces [immigrants] into irregularity, creating a system that benefits many, among other reasons, because it erodes labor rights,” says Itziar Ruiz Jiménez, a lecturer in International Relations at Madrid’s Autonomous University. She argues that “these policies are neither efficient, politically appropriate, or ethical.”

Immigration has been largely absent from political debate in recent years. Along with Portugal, Spain is unusual within Europe, because people here do not see immigration as a problem. In Spain, barely 3% of people put it among the main problems the country faces in recent surveys, says CIDOB.

The players were mistrustful of the two strangers who suggested they create a soccer team

This contrasts sharply with the openly xenophobic rhetoric heard in other European countries using half-truths and lies among immigrants, refugees and even the children and grandchildren of immigrants, in part bolstered by fear of Jihadist attacks, which are also a concern for Spain. Rejecting foreigners, particularly if they are Muslim, is a basic ingredient of the speeches and comments of Geert Wilders, currently favorite to win the Dutch elections, Marine Le Pen in France, or the fast-rising Alternative for Germany.

Alma de África suffered its first racist incident in February. Shouts of “monkeys” and “go back to your own country” so upset one player that he ended up being sent off. The side was losing 3-0 at that point. They subsequently launched a comeback. And won 3-4.

English version by Nick Lyne.