The gap that NAFTA was unable to close

Despite pledges, there’s been no per capita income convergence between Mexico and its trade partners

It is August 1992. The United States, Mexico and Canada have just signed a document agreeing to create the biggest free trade area in the world to date. The leaders from all three countries exchange congratulatory remarks and make bold predictions about the benefits of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

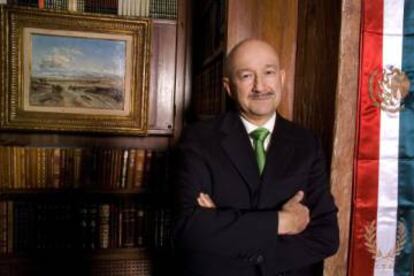

“The treaty means more and better paid jobs for Mexicans,” announced Carlos Salinas de Gortari, then the president of Mexico. His trade secretary, Jaime Serra, went even further: “The wage differential [between Mexico and the US/Canada] will tend to shrink over time.”

Neoclassical economic theories and observable trends in the previous five years (1988-1992) appeared to reinforce these views. But the reality has proved otherwise, even if living standards have risen in Mexico, as elsewhere in the world.

More than two decades after NAFTA was signed, the gap between the per capita income of Mexico and its partners has actually widened. World Bank figures show that between 1994 and 2015, average per capita GDP multiplied by a factor of 1.91 in Mexico, 1.96 in Canada and 2.02 in the US.

NAFTA was essentially about making it easier “for American companies to take advantage of cheap Mexican labor”

Elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean, average per capita GDP increased by a factor of 2.83, casting doubts over the benefits of NAFTA for Mexico at a time when the new US administration is questioning its very existence.

“Part of the idea behind NAFTA was this promotion of convergence, and that did not happen: salaries did not converge as expected, not by a long shot,” says economist Gerardo Esquivel of the Colegio de México institute of higher education. “This refutes the notion that all the benefits went to Mexico, as Trump holds.”

Although NAFTA was positive to the three partners in overall terms, the results have been a lot less favorable than people were told they would be.

“There’s been a group of winners and a group of losers, but net earnings growth in Mexico has been very weak,” says Esquivel.

Why did the forecasts about income convergence fail? Raymond Robertson, of Texas A&M University, points out several landmark events over the course of the last two decades.

“The Mexican peso crisis of December 1994 [the so-called Tequila Crisis] drastically reduced the wages of Mexican workers,” he notes.

Following that monetary crisis and the ensuing economic debacle, per capita GDP started a period of sustained growth until 2001, “although it never fully recovered.”

That year, the US entered a recession and China joined the World Trade Organization – a turning point for the Mexican economy. China’s accession “represented a greater source of competition for Mexico and pushed wages down.”

The treaty’s initial push was not sustained in time due to the absence of reforms

Monica De Bolle, Peterson Institute

Since then, he argues, and despite the Great Crisis of 2008 and 2009, which had much more of an impact on the United States, Mexican per capita GDP and workers’ salaries have been on a clearly different path from its neighbors to the north.

And that’s despite the fact that Mexico “has done what economic theory prescribed in order to achieve growth,” notes Robertson. “However, several external factors and events seem to have prevented the gap from closing.”

But productivity is the single factor that has slowed down the possibility of real convergence the most, says Monica de Bolle of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington DC.

“It was believed that the agreement would help income levels converge, but the gap has little to do with the free trade treaty and a lot more to do with productivity,” she says.

While labor productivity in the United States and Canada continued to grow after NAFTA went into effect, in Mexico it remained stable. De Bolle disagrees with Robertson about the Mexican authorities’ ability to introduce domestic changes that could have changed the course of events.

“The treaty’s initial push was not sustained over time due to the absence of reforms,” she says.

Roberto Durán-Fernández of McKinsey, agrees. To him, the 2012-2013 reform package introduced by President Enrique Peña Nieto came a decade too late.

“The NAFTA-driven push to the Mexican economy began to peter out much earlier than the 25 years that had been initially calculated,” he says. Added to this was a lack of investment, particularly painful in the infrastructure sector, “which has had a big effect because infrastructure conditions economic development.”

“From the moment the treaty was signed, there were two different Mexicos: a developed and industrial one that developed and industrialized further, fundamentally in the north, although not only there, with very good connections to the United States. There was also an unconnected one, fundamentally in the south,” he notes.

José Romero Tellaeche, director of the Center for Economic Studies at the Colegio de México, is most critical.

“Far from promoting greater industrialization, it has produced a slight de-industrialization,” he says. “And Mexico was left without monetary, fiscal and exchange policies, with the United States as the sole engine of growth.”

Romero’s view is that NAFTA was essentially about making it easier “for US companies to take advantage of cheap Mexican labor.”

“In the long run, this has caused an income gap between both countries and a buildup of resentment in the United States,” he adds. The end result is the election of Donald Trump as president.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.