Leading Japanese flamenco venue says “sayonara”

El Flamenco, epicenter of the Spanish music scene in Tokyo, closes its doors months before celebrating its 50th anniversary

Japanese social media began to rumble last March with rumors that Tokyo’s El Flamenco, the capital’s leading flamenco venue, was planning to close its doors six months before its 50th anniversary. The rumor proved true, and the venue – given the affectionate nickname Eru-futa, since Japanese pronunciation doesn’t include the letter L – celebrated its final show on July 26.

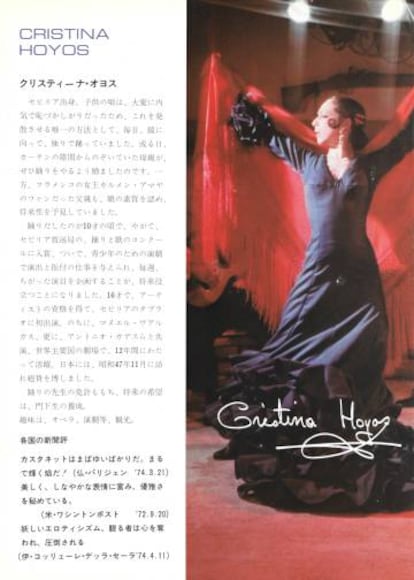

Located on the sixth floor of a building in the downtown Shinjuku area, the legendary spot is turning the page on a long romance between the Japanese people and the Spanish music and dance form, which was recently added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list. Over the five decades, some 900 Spanish artists had the opportunity to spend six months working at the venue and living in a furnished apartment 10 minutes away. Since Cristina Hoyos appeared at the 10th Anniversary show in 1976, just about every leading Spanish flamenco singer or dancer has performed here, reinforcing Tokyo’s position as the flamenco capital of Asia.

The venue will be sold to Sonia Johnes, a Japanese flamenco clothing company, which will reduce the number of shows, change the protocol for hiring artists, and invite a gourmet Spanish chef to take over the restaurant. The theater’s administrator for the past 40 years, Makoto Orihara, who will stay, denies that Japan’s affinity for the Spanish art form is diminishing.

Artists such as Jesús Ortega, Daniel Torres, Manolete, El Toleo, Rafaela Carrasco and Belén Maya have performed on the old wooden stage. Manolo Sanlúcar recorded an album there. At 18, Sara Baras danced as Javier Barón’s partner, and Eva Yerbabuena arrived at the venue when she was 19 soon after marrying.

Thousands of tourists sit and eat paella while the flamenco music fills the space

El Flamenco’s origins date back to 1964, when Tokyo had just held the Summer Olympics and wanted to attract visitors to cosmopolitan spots close to the city center. A flamenco club, with its trio of dancer, singer and guitarist, offered a familiar format to the Japanese geisha, shamizen, and singer combination. Both art forms incorporate handheld fans and colorful, flowery fabrics, and both tell tragic love stories with similar musical styles featuring falsetto and single syllables of text stretched over numerous notes.

The local tourist buses began to bring visitors by the hundreds, people who wanted a live show while they savored this strange plate of yellow rice with ingredients from the ocean called “pa-ey-ah.” If flamenco could be viewed as a Gypsy take on Japanese dance, paella could pass for sushi ingredients viewed through a multicultural Mediterranean lens.

El Flamenco’s origins date back to 1964, when Tokyo had just held the Summer Olympics and wanted to attract visitors to cosmopolitan spots close to the city center

El Flamenco will go down as one of the principal contributors to Spain’s stereotype as a “country of passion” (Jonetsu no kuni). The first team of artists was dismissed after an incident revolving around a beautiful Japanese flamenco dancer, Yasuko Nagamine, which ended with knives being brandished and the police making an appearance. After that, the Spanish performers’ contracts began to include an unspoken “peaceful coexistence” clause, at the recommendation of Cristina Hoyos, who became an indispensable consultant when it came time to recommend artists with both talent and a professional attitude. Orihara has amassed a long list of dramatic episodes that the administrator plans to someday put down on paper.

For the thousands of Japanese flamenco students, El Flamenco will forever be the place they went to (during the pre-cell phone, pre-YouTube era) with a hidden tape recorder poking out of their bags, hoping to return the next day to their school’s guitarist and ask him to recreate the melodies.

English version by Allison Light.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.