Javier Fernández, the new king of Spanish sport

The figure skating champion has risen to the top against all odds, fighting a complete lack of support from the state

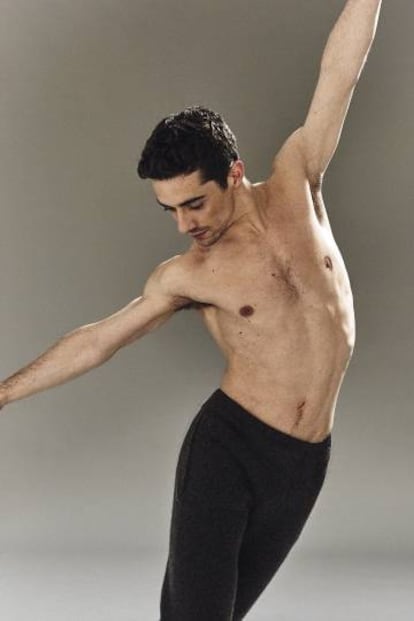

Who would have guessed that Spain’s next star would be a figure skater – a rebellious kid from a working-class background whose hard work and determination combined to make him twice world champion, and carve a legend on ice?

Enriqueta López had to take something to calm her nerves before going to Boston Garden, where a crowd of almost 20,000 was waiting to watch the 2016 finals of the World Figure Skating Championships.

She and her husband Antonio Fernández had spent a nervous few days since arriving in the US city, but they were resisting the temptation to speak to their son, Javier, for fear of distracting him.

It wasn’t easy. In the first short program of the World Figure Skating Championships, Javier had fallen and hurt himself. One of his heels had become so swollen that the doctor performed an infiltration to mitigate the pain. His main rival, a 21-year-old Japanese skater named Yuzuru Hanyu, had taken what looked like an unbeatable lead.

So on the evening of April 2, Enriqueta, a mailwoman from the Madrid district of Cuatro Vientos, and Antonio, an army mechanic, headed to Boston Garden expecting to be disappointed. As far as they could tell, their son would not be able to hang onto the world champion title, which he had won in Shanghai 12 months earlier.

Back in Madrid, their daughter Laura, who was once Spain’s best junior skater, was more confident. “I knew he could do it,” she says. “When a championship starts off badly, it takes the pressure off and it works out better.”

Javier has confessed that before a big competition he gets so nervous that even his hands shake, but this time he felt more relaxed. He realized that in order to win he would have to deliver a perfect performance in the long program. In fact, it was more than perfect. “It came out exceptional,” he says.

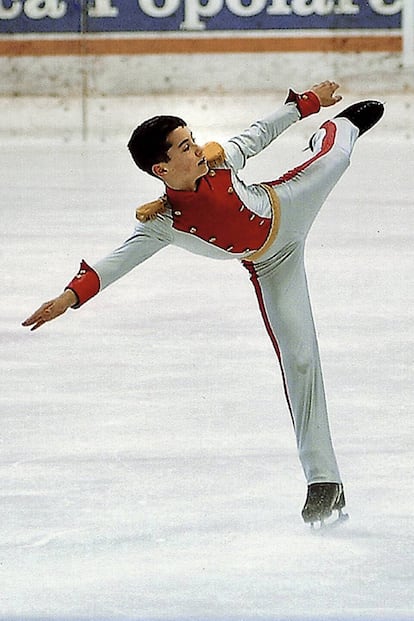

Before the end of the long program, the audience was already on its feet. Enriqueta and Antonio and Javier’s girlfriend – a Japanese skater named Miki Ando – were hugging each other and crying. For four minutes and 40 seconds they had watched Javier do pirouettes, his trademark quadruple jumps and whirling dervish spins. As he performed graceful arabesques to the sound of Frank Sinatra singing Guys and Dolls, one could see his face already lighting up with euphoria. It was, he says, the adrenalin rush that skaters feel when everything falls into place and they feel as though they are flying.

That night in Boston, Javier’s family, the 20,000 spectators and the jury all came away with the feeling that they had witnessed something unique. “A lot of people are saying it might be the best program they’ve ever seen,” says Javier’s Canadian coach Brian Orser, who trains both Fernández and his rival Hanyu in Toronto.

“It was a show of physical and mental strength without precedent in the history of figure skating,” agrees Daniel Peinado, Javier’s Spanish coach, while The Boston Globe wrote: “One of the best long programs ever seen. Maybe the best.” Even his rival Hanyu got down on his knees in front of Javier, returning the gesture the Spaniard had made to him four months earlier as tribute to an outstanding performance.

Five weeks after his triumphant night in Boston, Javier was presented with the Gold Medal of the Royal Order of Sports Merit by Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy. Whatever Rajoy asked, Javier’s answer was surely something along the lines of Yes, Mr President, four European titles and two world championships – in a row.

A minority sport

The Madrid native has had a run of success that the world of figure skating hadn’t seen for decades. And it has turned him into Spain’s sporting hero of the moment, a star in a discipline with scant national tradition, along the lines of Angel Nieto, Ballesteros or Alonso, who all excelled in minority sports.

There are fewer than 500 Spanish skaters at competition level. And there are only 17 skating rinks in the country, most of them private.

“Javier’s success is a miracle of Spanish sport,” says Peinado while Pedro Lamelas, the journalist behind the website Hielo Español, says, “The word miracle doesn’t even begin to describe it. It’s as though Messi had been born in Indonesia!”

After Boston, Javier – Javi or Javichu to his friends – might have deserved some downtime lounging on a beach, but instead he packed his bags for Japan. Most of his earnings come from shows, not competitions. And the Japanese will pay up to €300 each to watch him perform.

With the Japanese tour over, he spent four days in Madrid before going on tour in Canada, where he has been living for the past five years. Four hectic days at home, during which time he was received not just by Rajoy, but also by King Felipe and Queen Letizia. And then there was the day he accompanied Madrid regional premier Cristina Cifuentes on a hospital visit; and the days he was interviewed on all the main sports programs and asked to do the kick-off at Bernabéu football stadium.

He managed to fit it all in with a smile and some help from his old school friend and PR, Jorge Serradilla, who got him to his star engagements on time. Not that he was held up by crowds of fans. While he was stopped by a few people on the Gran Via, he was asked for ID by the hospital doorman as he made his entrance with Cifuentes.

In reality, Javier is more likely to be recognized on the street in Japan than in Spain. Because like so many young Spaniards, in order to get anywhere, he had to seek opportunities abroad with not much money to fall back on and no language skills, but driven forward by the knowledge that his family had sacrificed so much for his future.

A childhood dream

Enriqueta and Antonio have always supported their children’s skating ambitions. In fact, they were skaters themselves, albeit in a different league. When they were still dating, they would go to the ice rink at the old Real Madrid sport center or the Diamond rink in Aluche. Later, after Laura and Javier were born, they returned to the Diamond rink to take a look.

“Javi was really small. He was still in a pushchair,” Antonio recalls. “But his sister Laura who’s two and a half years older loved the ice.” She had, he said, seen skaters on TV and wanted to try it.

Javi’s family nickname was El Lagartija (the lizard) because he had a rebellious streak and wouldn’t sit still. And though he was introduced to the ice at six, it wasn’t until he was eight that he skated without a fight.

“I got hooked really quickly but I don’t know why it took me so long to get on the ice,” he says. “Sometimes my mother had to physically put me out there, but once I was on it, I couldn’t stop.”

He didn’t listen to his teachers and spent his time pulling the girl’s skirts or throwing ice at them. When eventually he started to focus, all the difficult moves, especially the jumps, came to him naturally. “He was incredible,” says journalist Pedro Lamelas. “His skates were so bad you thought, ‘This is going to break his knees!’ But he did the most amazing things.”

Soon he was mastering the double axel, a half-turn taking off with one foot and landing with the other. He didn’t care if he fell. “I don’t remember ever being afraid,” Javi says. But while Laura became a promising talent in the junior skating world, he was still debating whether to dedicate his time to tennis or soccer instead.

Then, Laura was offered a spot at the Jaca skating school in the Pyrenees, where her costs would be covered. “It’s an expensive sport,” says Antonio. “Between the two children we were spending €450 a month when my earnings were less than €1,500.”

So Laura went to Jaca with her mother, a move that offended the Majadahonda Skating Club, which subsequently expelled Javi. Six months later, he joined his sister in Jaca, leaving Antonio alone in Madrid.

“Javi wasn’t happy there,” says Laura. “Jaca is a small town. The children like other sports and they teased Javi, saying that skating was for gays.”

So they returned to Madrid after two years. Laura was out ahead, but Javi decided to stop skating and play hockey instead. “He was discouraged, he hadn’t improved and he didn’t feel supported by the coaches or the clubs,” says Laura, who for similar reasons gave up skating at 20 to study nursing.

But a summer camp in Andorra changed everything. One of the coaches was Russian skating guru Nikolai Morozov, and he singled the 17-year-old Javi out. “He could see he was a rough diamond,” says coach Daniel Peinado. “Without that encounter, we wouldn’t have a world champion today.”

Sign up for our newsletter

EL PAÍS English Edition has launched a weekly newsletter. Sign up today to receive a selection of our best stories in your inbox every Saturday morning. For full details about how to subscribe, click here.

Morozov offered to take Javi to America. He wouldn’t charge to coach him, but his family would have to pay the expenses. “He made me give him an answer immediately,” recalls Javi. “So without mentioning it to my parents, I said yes.” When Enriqueta and Antonio did find out, they asked if he was sure and he told them, “It’s a dream. I want to try it.” To which his father replied, “You’re not just going to try it, you’re going to make it.”

Antonio used some savings he had set aside to refurbish the apartment in Cuatro Vientos, and he found an extra job in the afternoons fixing helicopters while Enriqueta got a job at the post office. With scarcely any English, Javi left Spain and went to live in an apartment in New Jersey, which he shared with a Spanish coach he knew from Jaca, Mikel García. García helped him with his English, the cooking and life in the States.

“It was very hard,” says Javi. “And the financial problems were very frustrating.” Expenses included trips, kit – his skates cost around €1,000 – and choreographies, which can be as much as €10,000.

“We didn’t have any grants or financial support from any government body,” says Antonio. “We were paying out between €2,000 and €3,000 a month. And the Spanish skating federation took it really badly when he left. When he came back to compete, they hardly spoke to him; they pretended not to know him.”

Sadness in Sochi

Morozov’s troop of skaters was nomadic. In the following two years, Javi moved between Moscow and Latvia, living in residences for sports competitors where the loneliness became unbearable. But Morozov’s methods produced results and in 2010, Javi became the first Spanish skater since 1956 to qualify for the Olympics.

In the actual games, he came in 14th. Morozov began paying more attention to another member of the group, Frenchman Florent Amodio, who was getting his coaching paid for. Javi needed a change. He was looking for a more stable lifestyle so he got in touch with veteran skating star Brian Orser, who was coaching an elite group of skaters in Toronto.

“When Javi arrived, I could see he had talent but he was lost,” Orser told the Toronto Sun recently. “He didn’t have much discipline or direction and there weren’t a lot of people who really believed in him.”

In Toronto, Javi learned to hate the Canadian winters but felt totally at home on the ice. “Brian has been like a second father to Javi,” says Antonio without a trace of jealousy. Besides the emotional support, he did a great job of bringing Javi on, and in 2013, the young Spaniard took the European Championships by storm. The following year he won again and was chosen to be the standard bearer for the Spanish at the winter Olympics in Sochi.

But despite the honor, Sochi would not produce happy memories for Javi. Being a Russian city, there had been controversy among the Olympic contenders over Putin’s homophobic policies. Unused to the media, Javi was reported as saying that gays “should keep quiet” during the Olympics to avoid problems. The comment was picked up immediately by the social media, and he had a rough time. “He even had death threats,” says one friend.

You’re not just going to try it, you’re going to make it

Javier's father, Antonio

“I couldn’t resist looking at the comments,” says Javi. “To see what they were saying about me. It reduced me to tears. I didn’t understand anything. I didn’t even remember what I’d said in the first place. How was I going to be anti-gay when this sport is full of gay people, when they’re my friends and even my coach is gay? It would be like hating everything around me.”

Although Javi maintains otherwise, the fallout seemed to affect his performance and his hopes of an Olympic medal were dashed. Though he did better than Vancouver, he didn’t get beyond fourth place.

But he dusted himself off and bounced back. In the following two years, he won two more European championships and bagged the world champion title in 2015. Life started to get easier. Financial support materialized in the form of a grant from the Superior Sports Council that covered his living expenses and travel. He even had two Spanish colleagues in Toronto – Javier Raya and Sonia Lafuente, one of the little girls he used to throw ice at. He began to feel more at home in general, a development illustrated by his use of a bike to get around the city in the absence of a Canadian work permit and the right to a driving licence.

The life of a skater is short. The joints in their legs wear out and they lose flexibility and movement. By the time they’re 30, they’re no longer able to compete at the highest level. “I’m hoping to still be around for the 2018 Olympics, and then we’ll see,” says Javi.

Those who know him say he will probably continue to attempt ever more difficult pirouettes. “He takes risks – it’s in his nature,” says Peinado.

But there will come a time when he will have to hang up his skates and bow out of the main arena. And, as premier league figure skating, unlike its equivalent in soccer, will never make him rich, he will have to find a way of making a living.

For now, he thinks he may return to Spain when he retires to set up a skating center in a bid to make skating more mainstream. Enriqueta and Antonio are happy with that. In fact, they are just happy he has achieved his goal. This summer they will be able to refurbish the apartment in Cuatro Vientos, the one they were going to revamp eight years ago before they invested the money in Javi’s dream.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.