Fukushima: Contaminated lives

The first major virtual reality feature in Spanish media investigates how the 2011 Japanese tsunami changed the course of the country’s history

Mr Toyotaka Kanakura’s favorite flower is the Persian Buttercup, a multi-petaled plant that once flourished in Namie, Kanakura’s hometown on the northeast coast of Japan. He sold them in his florist shop, a thriving business prior to March 11, 2011. On that fateful day, at 2.46pm, he was finishing off his lunch after decorating the graduation hall of the local high school, when a magnitude-nine earthquake struck some 130 kilometers off the coast, rocking the sea bed and shattering the lives of thousands of unsuspecting Japanese.

He ran home and spent the night staring at the cracked ceiling of his house. At 6am the next morning, he heard the evacuation alert and, several minutes later he had joined the rest of Namie in a mass exodus while police cars and fire engines headed in the other direction. He only put a few things in his case – he didn’t think he would be away so long.

[Click on the video below for the virtual news report. If you are on a mobile device, download the YouTube app for a clearer picture. You can also watch the report by downloading the El País VR app. For more information read this story]

A slight, reserved man, Kanakura nods and lowers his gaze. Japanese people are not generally given to expressing their feelings, he says, but he is clearly upset as he explains how much he has missed his work and his customers since March 11, 2011. His store sign, half covered by planks of wood, still reads ‘The Prettiest Flowers.’

Once home to 19,000 people, Namie has been turned into a ghost town. Situated eight kilometers from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, it falls within the 20-kilometer exclusion zone. To reach Daiichi, you have to protect yourself with rubber boots, gloves and a mask. There is an electric fence that obliges you to enter through a police checkpoint where they can measure radiation levels. Former residents can only return once a month with government permission. It is the ground zero of the disaster.

Evidence of the exodus has been frozen in time. In some houses, the doors have been left ajar, allowing monkeys and wild boar to use them for shelter. Others have their windows broken and the curtains blow desolately through the empty panes. There are plates of food on the tables, piles of hastily discarded clothes in the wardrobes, notes on fridges with lists for a week long gone and family photos in a muddle in open drawers. In the town, some shops have mannequins still wearing 2011 fashions and in the barbers, the scissors and electric hair clippers still bear the traces of their last haircut. But there is no sign of any Persian Buttercups. There is no sign of any flowers at all. In their place are huge dosimeters that alert the workers to the radiation levels as they try to reconstruct the worst-hit areas.

Former residents can only return here once a month with government permission. It is the ground zero of the disaster

The coast took the brunt of the disaster in more ways than one. First, a 15-meter wave destroyed everything in its path. At a crossroads, a traffic sign and some toilets are all that remains of a school. Of the 21,000 who lost their lives to the tsunami across the country, 200 died here. But that was only the beginning. Next, the Fukushima nuclear plant started to leak radiation that seeped insidiously into the atmosphere, the soil and the Pacific Ocean. According to experts, it will take 300 years for the environment to return to normal.

One of the most frightening things about radiation is it that it is an invisible enemy. It doesn’t smell and has no perceptible taste in food and water. It exists in dust particles in the air and in the soil, and on furniture. Its levels can change drastically here. Since the disaster, people have had to use radiation gauges as they move about within the exclusion zone, taking care not to swallow or inhale the particles; internal radiation can be devastating, passing easily to the blood and causing Leukemia.

The worst culprits are radioiodine, which causes thyroid cancer in children, and cesium 137, an isotope that has a half-life of 30 years. Cesium 137 is everywhere here and the levels are above 2 microSieverts an hour (µSv/h): the government aims to get this figure down to 0.27 before it starts resettling families. In spite of this, Mr Kanakura, who currently lives outside the exclusion zone, has heard rumors that some people remain within the zone, shut inside their houses, living like ghosts.

One thing that will last longer than exile will be the stigma of having lived in the Fukushima area. For years to come, nobody will want products bearing the name Fukushima and many Japanese from other parts of the country are distrustful of the evacuees. Just like the hibakusha after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Fukushima victims are suspected of deliberately spreading radiation so they can claim compensation – so far around €50 billion has been paid out to more than a million-and-a-half victims.

The psychological damage to the evacuees is arguably worse than the threat of cancer. Around 14.6% of the victims are affected by depression and mental illness compared to 4.2% of the general population, according to a study carried out by Dr Koichi Tanigawa. Among those from the Fukushima district, there has been a vertiginous rise in suicides. As John Hersey noted in his Pulitzer-Prize winning book Hiroshima, those who survive will be forever stigmatized.

One of the most frightening things about radiation is it that it is an invisible enemy. It doesn’t smell and has no perceptible taste in food and water

It has been 70 years since Hiroshima but Hiromi Hasai remembers it as though it were yesterday. At 8.15am, he had just started his day at an arms factory where he was learning to make bullets for machine guns. Suddenly, everything lit up by “a light brighter than the sun,” he recalls. “Then the windows started to shake and I ran out. Everyone was saying that a bomb had fallen on their house but there was no sign of a plane. It was impossible.”

He was 15 kilometers from ground zero where “Little Boy” was dropped from an American jet and exploded with around 15 kilotons of energy. Now a retired nuclear physicist, Hasai, 88, campaigns against nuclear power, particularly in countries prone to earthquakes like Japan. “They said that nothing like Chernobyl or the Three Mile Island would ever happen here. But it did. We were able to avoid the massive explosion but we don’t know what will happen with the leaks and the safety of these devices is still in question.”

Until the meltdown, Japan had 54 nuclear reactors producing 29% of the country’s energy. Many were built in seismic zones but Japanese scientists did not consider a magnitude-nine earthquake possible off the coast of Tokohu. Forced into taking some responsibility for the meltdown, Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) admitted: “We were guilty of negligence for not implementing better safety measures and for thinking we had enough with what we had […]. If we had implemented them before, the disaster could have been averted.”

As much as 800 tons of radioactive waste has been leaked into the sea so far and Tepco admits that the cleanup operation will take 40 years or more. Meanwhile, three former directors of Tepco have been charged for not taking steps to avoid the meltdown.

Though Fukushima has turned the majority of Japanese against nuclear power, the current Japanese government led by Shinzo Abe wants to restart as many nuclear reactors as possible (three are currently in operation), sending a message to the world that it’s business as usual.

So far the meltdown has cost the country around €170 billion, with the task of decontaminating the affected areas still very much in progress. Every day, an army of operators takes a five-centimeter layer of topsoil from around the houses within the exclusion zones and fills thousands of black bags, which are stacked at the entrance of each town.

Until the meltdown, Japan had 54 nuclear reactors producing 29% of the country’s energy

But the task can seem futile. In the mountainous areas, the radiation in the trees penetrates the soil each time there is rain or a gust of wind. In Litate, 60 kilometers from the central prefecture, residents are being allowed to return during daylight hours while a level of 10 microSieverts of radiation an hour is still being recorded.

Mr Toru Anzai, 63, wanders around the house he abandoned five years ago with plastic bags on his feet and his hands in the pockets of his blue anorak. He has been rehoused in a government block with others from Litate. He doesn’t like his new home. Two years ago, he had a heart attack and a stroke and it seemed as though the stress and insecurity of his situation was killing him. But in the hospital they found a hole in the frontal lobe of his brain that was producing paralysis down the left side of his body. The doctor said it could have been caused by absorbing cesium over a period of time. “We kid ourselves about the levels of radiation,” says Mr Anzai. “What’s the use of compensation? I’ve lost everything: my life, my land, my memories… I’m very angry and every time I come here, I go to pieces.”

The clocks on the walls of Mr Anzai’s home stopped shortly after the disaster; not long after he was ploughing the family paddy fields and soon after he felt the earth begin to move beneath his feet. As a farmer, Mr Anzai was never happy about the nuclear plants. He ran home and filled a number of carafes with water. Something told him he shouldn’t drink from the tap. He then shut himself inside with his five brothers and two days later, on March 14, he heard a thunderous noise as reactor two exploded after its cooling system failed. It didn’t take long for the wind to bring the penetrating smell of melted iron mixed with sulfur to Litate as a massive toxic cloud blew towards his home.

In spite of the mayor of Litate’s assurance that there was no risk of radiation, Mr Anzai bought his first dosimeter on April 18. It cost him €500 but the information it gave him was invaluable: the radiation in the room where he and his brothers had been sleeping for the past month was at six microSieverts an hour – 20 times higher than the level stipulated by the government for relocating residents. Anzai and his neighbors in Litate were exposed to the highest levels of radiation of anyone in the area.

El País Semanal accompanied Greenpeace for two days while they measured the radiation still being released by the central prefecture of Fukushima. The easiest way to do this is by measuring the mud in the ditches. The levels there are still far higher than the “safe” level fixed by the government, which is trying put an end to the emergency situation and cut the €700 a month benefits received by evacuees.

“It’s impossible to get rid of the waste even in normal circumstances,” says Raquel Montón, who runs Greenpeace’s anti-nuclear campaign. “But when there’s an accident, it’s unrealistic to think there is another solution besides time. The decontamination process, which isn’t working, obscures a strategy aimed at getting people back to homes that are still not free of radiation. All this so the reactors can be restarted.”

The land of the living is contaminated, but also the land of the dead. In many of the towns within the exclusion zone, the cemetery has undergone the same decontamination process as the rest of the area and the operators have had to go digging around in recently dug graves whose headstones have been covered in some cases by black tarpaulin.

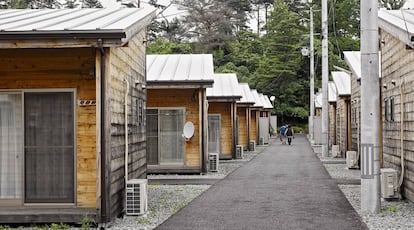

Where once there were paddy fields, there are now mountains of black bags waiting to be incinerated in the decontamination depots. They have already disposed of 9.5 million bags but there are still 13 million to go before they will have cleaned up an area twice the size of Madrid. Meanwhile, the lives of the evacuees move slowly forward in the prefabricated houses that line the frontier of the exclusion zone.

The camp of Portacabins in Koike 1 is located between a cemetery and a factory on the outskirts of Minamisoma, 30 kilometers from the Daiichi plant. The only thing separating the tiny 15m2 dwellings that house 200 people is a flimsy wall. At 11am Mrs Inaride Yuko is on her way home after doing her shopping and gets shakily off the bus with a bag full of rice cakes. Her knees can scarcely support her weight and she walks with the help of a stick. At the bus stop, there’s a sign that says Love Station. It’s an example of the Japanese tendency to take the sting out of reality with an ingenious, almost childish stroke.

But this hasn’t done much to help Mrs Yuko. At 73, the only thing she looks forward to is her drink of Okinawa sake. Anything else gives her a sore head. She has one glass in the morning and another before she goes to bed. It saves on sleeping pills and helps her get through the lonely days in the camp.

On March 11, the tsunami swept away her home, which was located a kilometer from the coast. She and her son were saved by a miracle. The previous night they had felt a slight warning tremor and got the car ready for a quick getaway in the event of something bigger. Which, of course, came the next day. Their dog went crazy minutes before it happened and, taking heed, they fled to a nearby hill and watched as the sea descended on their home.

Mrs Yuko thought she and her son would have a new house, maybe one made of wood from Finland. This is what she thought at the time, she recalls, as she takes off her gloves and prepares a pot of green tea. She bends her knees as best she can and lowers herself onto a futon to show some mementos from her previous life, such as a postcard from the Malaga town of Ronda. Much of her past life is stored in see-through boxes.

Most who either lost their homes or had to evacuate them live in these kinds of camps. But there are also those who ignored the government evacuation order, such as Professor Takashi Sasaki, 76, and his wife, who suffers from Alzheimer.

At first they were scared – at night, their town is deserted and in total darkness. But then they started to think that their neighbors in the camps had it worse. For example, 200 of the old and infirm died from the upheaval when the government made the mistake of sending them back to Litate and then evacuating them again. The professor, a Hispanophile who loves Miguel Unamuno, paraphrases the author to describe his situation: “Our biological lives go on but our biographies have been stolen.”

Sasaki, who has written a book called Fukushima, Living the Disaster and has his own blog, is not worried about being contaminated. He and his wife, who lies in the room next door, will die before the radiation can take effect. What troubles him is that nobody is taking responsibility for what has happened. “They say it was an accident. But it’s actually the result of having lost the essence of our culture, our contact with nature, our measured approach to work, our ceremonies… We have failed in terms of our education and our traditions. Nowadays, the Japanese gods are convenience and progress. Nuclear energy is a reflection of that and the accident is a direct consequence.”

On the morning of the accident, Japan’s then-prime minister, Naoto Kan, replied to questions from Parliament’s Financial Commission. He had been in power for scarcely a year and but with the yen through the roof and imports in freefall, he was running out of time. After the earthquake, which hit Tokyo with a magnitude of 7.4 on the Richter scale, he aborted the meeting and rushed downstairs to the emergency room. “The first news we had was that other reactors in the region had been shut down correctly,” says a spokesperson from Greenpeace, whose ship Rainbow Warrior is sailing up and down the Fukushima coastline. “An hour later, they gave us information on Daiichi and said the power had gone.”

As the ship comes within a kilometer or so of the nuclear plant, the spokesperson goes on to explain that Tepco lowered the geographical level of the site to take advantage of the sea’s power. “If they hadn’t done this,” she says, “the tsunami might not have hit the plant with such force.”

Kan, now a shunned ex-prime minister with a damning legacy, takes responsibility for what happened. He remembers ordering the director general of the plant and his employees to stay put when it looked as though Daiichi could explode. And, of course, like everyone who belongs to the country’s establishment, he approved nuclear energy and actively promoted it on an international level. Now he is seeking to redeem himself.

On board the Rainbow Warrior, he is asked if he feels guilty.

“Of course,” he says. “And, above all, responsible. I now believe that all nuclear plants should be closed.” Fukushima is just a warning, he says. The question is not whether something like it could happen again, but when and where.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.